Bail bonds require posting money by or on behalf of someone charged with a crime in exchange for their release before trial. In theory, the money backs a promise by the accused to appear in court as scheduled and to be of good behavior. If the accused violates the terms of release, by fleeing the jurisdiction or committing another crime, they can be imprisoned and required to forfeit the bond.

In RI, State Rep. Anastasia Williams (D-9, Providence) is the lead sponsor of H.5291 that would prohibit the imposition of bond for misdemeanor defendants except in cases of domestic violence or if the court makes a finding that there is a likely risk of flight or obstruction of justice by, for example, threatening witnesses. In an interview with Motif, Williams said, “The intent of the bill is two-fold: one, not to financially burden an individual to come up with money that they don’t have; and, two, remove the burden off the taxpayers when, in fact, this individual must remain in jail because they can’t put up the bail for the minor infraction that he or she is there for.”

Even short stints in jail of a few days can be devastating to poor people, Williams said. “You have these individuals who, for whatever reason, end up committing a crime, it’s their first one. They’re working at a minimum wage job, it’s the only means for daily survival. They don’t have a bank account with any type of reserve, and they’re held in the prison for the weekend: They end up losing their job, they end up not having the money to pay bail, then when they get their court hearing the stuff is dismissed. There goes, that person lost everything.”

In most cases, RI requires only a “surety” bond, posting 10% of the bond amount. (Where the charge involves a debt arising from a criminal sentence, such as failing to pay fines or restitution, a “cash” bond of 100% of the debt can be imposed.) Some people have enough money to post the surety amount from their own cash, and others may have non-cash assets, such as real estate, that they can use for this purpose. Some people can borrow money or assets from parents, relatives or friends. People who are short of cash but have acceptable credit can arrange to borrow the money from a bail bond agent and pay back the loan over time with interest. (For-profit bail bond agency is illegal in some states, but allowed in RI.)

People with access to none of these resources – neither cash, nor assets, nor credit – cannot post bond and must instead remain in jail awaiting trial. Because of this, the bail bond system has become controversial because of its effect on poor people, who are disproportionately racial and ethnic minorities, and the potentially life-destroying consequences of being caught up in it.

“How many people do they get on a daily basis, or weekly or monthly, go to jail? You don’t see a whole bunch of white folks,” Williams said.

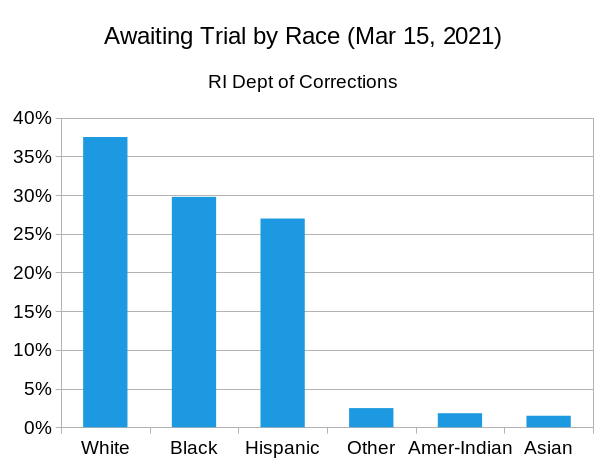

At the request of Motif, J.R. Ventura, chief of information and public relations officer at the RI Department of Corrections, provided a snapshot of prisoners awaiting trial counted by race. (Prisons keep track of race in order to protect the prisoners from inter-racial violence.) As of March 15, 2021, those awaiting trial were 37.50% white, 29.77% Black, 26.97% Hispanic, 2.47% other, 1.81% Amer-Indian, and 1.48% Asian. By contrast, the population of RI is 71.4% white (non-Hispanic), 16.3% Hispanic, 8.5% Black, 3.7% Asian, and 1.1% Amer-Indian.

Everyone charged with a crime is presumed innocent until proven guilty, and the alternative to posting bond is known as “personal recognizance” where no money need be posted in advance, but violating the terms of pre-trial release can result in being jailed and required to forfeit the amount specified. For example, a defendant released subject to $10,000 bond must post $1,000 to stay out of jail and forfeit $10,000 if they violate terms of release, but a defendant released subject to $10,000 personal recognizance must post nothing to stay out of jail but forfeit $10,000 if they violate terms of release.

At a February 9, 2021, House Judiciary committee hearing on Williams’ H.5291 bill, the Office of the Rhode Island Public Defender offered testimony in support; by law, the office represents indigent criminal defendants who are, because of their indigence, most likely to have trouble coming up with money to post bond.

In an interview with Motif, Assistant Pubic Defender Michael DiLauro said that the office had filed Access to Public Records Act (APRA) requests to determine how long defendants stay in jail while trying to post bond. “How many people get detained because they can’t post bail? So the easy conclusion to draw was that a very, very, very high percentage bordering on, bumping up against, 100% of people charged only with misdemeanors post bail within 14 days of their arraignment. The troubling thing is the amount of time that it took them to make bail. Everybody’s gonna get out. The point, I think then, is why are we detaining them in the first place? That to me is the issue here in Rhode Island. When you look at those numbers, you can see that a pretty significant number get held one day, then a few get out; two days, a few more get out; three days, a few more get out; and probably by day five or six, 90-plus percent of the people are out of jail. Which again begs the question: Why are they being detained in the first place?”

DiLauro echoed Williams’ concern about these short stays in jail of only a few days having disastrous consequences. “Because they’re all going to get out anyway, what’s the point? The damage is done. We know from the research that the damage that is done is pretty, pretty, pretty, pretty severe: housing, employment, all those types of things. That was our proposal to try to get our system to work better, to strengthen the presumption of personal recognizance that’s already a part of Rhode Island law.”

At the same hearing, the RI American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) entered a statement by Steven Brown, executive director: “For individuals who are lower income, the burden of cash bail is often something that they are unable to overcome, even when the amount may seem relatively small. Without an immediate cash flow, or without the use of predatory for-profit bail businesses, they are oftentimes forced to stay in jail until their case is heard, while wealthier individuals who can post bail are permitted to go home while awaiting their hearings. The effects can be devastating. Even a stay of just a few days in jail can lead to a person’s loss of their job, missed payments and other life disruptions that can be very hard to undo, no matter the outcome of the criminal charges. It can force a person to plead to a crime that they are not guilty of. It can make it harder for them to prepare a defense. The list of direct and collateral consequences goes on and on.”

Asked by Motif for their position on the bill, even the office of Attorney General Peter Neronha, responsible for nearly all criminal prosecutions in the state, was broadly supportive: “An individual’s financial status should not prevent him or her from qualifying for pre-trial release when he or she would otherwise meet the legal criteria for release. We need a holistic approach to cash bail reform that accounts for the views of all stakeholders in the criminal justice system, as well as evidence and data from other states that have enacted such reforms.”

As of this writing, H.5291 remains in committee “held for further study.” If reported out favorably, it would be voted by the full House, and if passed begin a similar journey at the Senate Judiciary Committee.

On the one hand, everybody acknowledges that some criminal defendants are flight risks or too dangerous to be released pending trial, but there is an emerging national consensus that distinguishing who should and should not be released pre-trial has no rational relationship to how much money they have. Bail bonds have a long history dating back to English Common Law in the American Colonial Era, and the Bill of Rights in the US Constitution provides in the Eighth Amendment that “excessive bail should not be imposed,” echoing a similar provision from the earlier English Bill of Rights of 1689.

California is one state that tried bail reform, with the legislature eliminating money bonds entirely in 2019, but this was overturned by referendum in 2020; on March 25, 2021, the state Supreme Court ruled that money bonds are unconstitutional. “The common practice of conditioning freedom solely on whether an arrestee can afford bail is unconstitutional,” the court said in a unanimous opinion. “Other conditions of release – such as electronic monitoring, regular check-ins with a pretrial case manager, community housing or shelter, and drug and alcohol treatment – can in many cases protect public and victim safety as well as assure the arrestee’s appearance at trial.”

A highly publicized case in New York has been the inspiration for a national bail reform movement, that of Kalief Browder. Placed on probation for joyriding at age 16 but charged as an adult under New York law, when Browder was arrested 10 days before his 17th birthday and accused of stealing a backpack two weeks earlier, he was denied bail and held awaiting trial in prison at Riker’s Island. He was repeatedly offered plea bargains that would have gotten him out of prison immediately, but he insisted that he was innocent and refused to plead guilty. Because of repeated delays at the overworked and backlogged prosecutor’s office, he was finally freed four days after his 20th birthday: The charges were dropped because the complainant had gone back to Mexico and could not be found to testify. Of the more than three years Browder spent in prison, two were spent in solitary confinement because of fights with other inmates, guards were recorded on video beating him while he was handcuffed, and he tried several times to kill himself. The long incarceration, especially in solitary confinement, left Browder with serious psychological problems, including depression and paranoia, and he was in and out of mental hospitals. Finally, a few days after his 22nd birthday, he committed suicide by hanging himself outside his mother’s apartment. His family settled with the City of New York for $3.3 million.