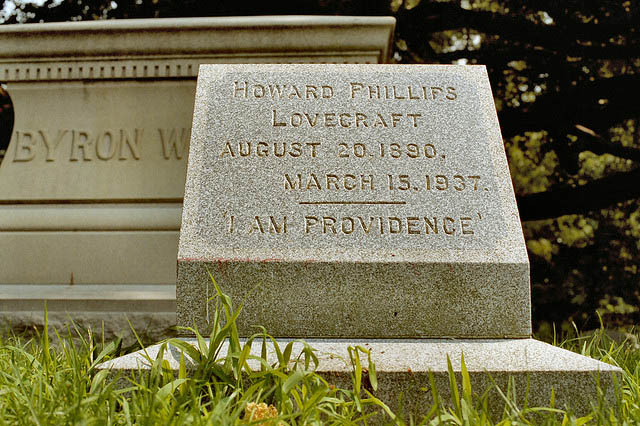

Obscure for all of his life and only slightly less obscure for decades after his death in 1937, horror writer H.P. Lovecraft, like one of his fictional creatures, quietly waited under the earth of Swan Point Cemetery in Providence for an auspicious time when the author’s reputation, if not the author himself, would re-emerge. Presciently tapping the anxieties that would come to define science fiction in the age of atomic warfare and primitive space exploration, Lovecraft received his first biographical treatment in 1975 by fellow legendary author L. Sprague de Camp.

Obscure for all of his life and only slightly less obscure for decades after his death in 1937, horror writer H.P. Lovecraft, like one of his fictional creatures, quietly waited under the earth of Swan Point Cemetery in Providence for an auspicious time when the author’s reputation, if not the author himself, would re-emerge. Presciently tapping the anxieties that would come to define science fiction in the age of atomic warfare and primitive space exploration, Lovecraft received his first biographical treatment in 1975 by fellow legendary author L. Sprague de Camp.

It was de Camp’s book that Carl Johnson would find when he decided to commemorate the 50th anniversary of Lovecraft’s death on March 15, 1987. He noted the favorable confluence of the Ides of March date falling that year on a Sunday with a full moon. Johnson, now an historical interpreter and guide at Slater Mill Historic Site, is a local native who said that his ancestry ties his family to Lovecraft at several points – including that Johnson’s maternal grandfather and Lovecraft’s maternal grandmother were first cousins – discovered that his own Wayland Square residence was about halfway between the Phillips family home on Angell Street where Lovecraft lived for much of his childhood and the Barnes Street house where Lovecraft lived in his later years.

Johnson said that he wrote in East Side Monthly and the now-defunct Providence Eagle inviting the public to gather at Lovecraft’s grave site. “I expected a dozen horror fiction fans, but my phone started ringing. One hundred people attended,” he said, including Lovecraft biographer and editor S.T. Joshi. Johnson and his twin brother Keith continued the tradition of dramatic recitations, poetry readings and songs annually until 1992. After a hiatus, the commemorations recommenced in 1998, moving to the Ladd Observatory of Brown University where Lovecraft had been a frequent visitor and keen amateur astronomer. Presided over by Christian Henry Tobler as master of ceremonies, Johnson said that “folks are encouraged to dress in vintage or gothic attire, and many do.” The 2013 event drew about 140.

One of the consistent presenters has been poet and small-press publisher Brett Rutherford, who moved to Rhode Island in 1985 in what he termed a “Lovecraft and Poe pilgrimage” partly influenced by de Camp’s book. Although Rutherford said he has been a science fiction fan since age 6, in the late 1950s at age 15 he read The Colour Out of Space in an anthology and it “threw me for a loop, because it wasn’t like anything else.” He said he wrote a letter to Lovecraft’s friend and fellow writer August Derleth “who wrote back very kindly. I never told him I was only 15, because I was too stupid and proud to tell him I was just a kid.” He said that he still has Derleth’s letter.

Rutherford is the author of a 1993 biographical play about Lovecraft, Night Gaunts, named after the term Lovecraft used for his childhood night terrors. Performed several times at the Providence Athenaeum with Carl Johnson in the role of Lovecraft, Rutherford said that his play still attracts interest from as far away as Germany where it was staged in 2006, and that a college radio station in Massachusetts performed it on-the-air for Halloween in the 1990s. According to Johnson, a photograph of him in costume and makeup from the play is often erroneously misidentified as Lovecraft himself, including at least twice by The Providence Journal.

At the commemorations Rutherford usually reads “The Tree at Lovecraft’s Grave” (an allusion to Lovecraft’s own early short story “The Tree”) that he described as “an American Transcendental poem” he considers one of his best. Incorporated into his collection Whippoorwill Road: The Supernatural Poems (now in its 5th edition), its elegiac tone was enhanced when the actual tree that was its subject was cut down. “Many people imagine Lovecraft as being this grim, depressed person with a dark view of life, but the gothic is an entertainment, walking on a tightrope over a dark view of life,” he said. “I call this ‘the smile behind the skull.’”

Some of that smiling has been done by Thomas Broadbent, who annually organizes a “birthday bash” at Lovecraft’s grave site on the Sunday closest to his August 20 birth date, “with a birthday cake, balloons, readings and a jolly good time.” Lighter in tone and typically with better weather than the March commemoration, the purpose is, he said, to “honor Lovecraft and give him the birthday party he never had.” The event typically draws about 50.

Broadbent’s interest was piqued decades ago when he was 14 by his older sister who gave him The Colour Out of Space – the same short story that originally caught Rutherford’s interest – to read, which he said was “creepy even though I didn’t quite get it. At 14 you expect all horror to be like a horror movie.” He administers an active Facebook discussion group, “Lovecraft Eternal,” with about 1,000 members, and is among a number of subscribers to the “H.P. Lovecraft Bronze Bust Project” to commission a work by sculptor Bryan Moore that will be installed at the Providence Athenaeum in August 2013.

“Locals held Lovecraft rather in scorn” and “were somewhat embarrassed by him,” Rutherford said, but this has changed at least since the Library of America edition of Lovcecraft’s works in 2005 effectively made him part of the literary canon. “One thing Lovecraft truly did love was Providence,” Rutherford said, adding that he personally knows “at least a dozen visual artists, writers, poets and students” who, like him, moved to the city at least partially because of their interest in Lovecraft. Broadbent said he was pleased with the decision of the Providence City Council, reported by the Associated Press on July 17, to designate the intersection of Angell and Prospect Streets as “H.P. Lovecraft Square.”

“Locals held Lovecraft rather in scorn” and “were somewhat embarrassed by him,” Rutherford said, but this has changed at least since the Library of America edition of Lovcecraft’s works in 2005 effectively made him part of the literary canon. “One thing Lovecraft truly did love was Providence,” Rutherford said, adding that he personally knows “at least a dozen visual artists, writers, poets and students” who, like him, moved to the city at least partially because of their interest in Lovecraft. Broadbent said he was pleased with the decision of the Providence City Council, reported by the Associated Press on July 17, to designate the intersection of Angell and Prospect Streets as “H.P. Lovecraft Square.”

Informal societies humorously took their names from monstrous characters in Lovecraft’s fiction, Rutherford’s “Cthulu Prayer Society” and Broadbent’s “Esoteric Order of Dagon,” comprising “pockets of admirers who didn’t know each other,” as Broadbent described them, “who would just sit in cafés and chat.” As a committed scientific materialist and atheist, Lovecraft likely would have found these facetiously named societies amusing, but according to Rutherford, people would sometimes take them seriously as a religion, which he found ridiculous. Distributing the CPS newsletter to a library, he said he was once told, “You people are nuts!”

In addition to regular monthly meetings at a bar, the CPS went on field trips, including until 2009 annual picnics in Lincoln Woods where Rutherford, relying on letters describing the view of the horizon and terrain, said he was able to identify the exact spot on a rock ledge where Lovecraft liked to sit while writing. According to Rutherford, Lovecraft (who did not drive) recounted his visits by means of “a couple of trolleys and a bus.”

Some of the scorn and embarrassment about Lovecraft, as Rutherford phrased it, is undeniably due to the overtly bigoted views expressed in his fiction and even more so in his voluminous letters. Rutherford said, “I certainly don’t forgive, but I understand,” and he believes that Lovecraft’s relatively insulated and isolated life led him to profess theoretical principles that he often flouted in practice. “In his loyalty to his friends, he came to see people whose intellect he respected,” Rutherford said. “Even when I show his prejudice [in Night Gaunts], I am able to show him as human. His wife Sonia, who is Jewish, gets to break through, and she has to be an exception.” Johnson said that Lovecraft’s views were probably fairly common for his era and circumstances, even if “horrifying by our standards.” Broadbent said, “Lovecraft’s racism gets under my skin a lot, but I ignore it as much as I can.”

Lovecraft’s consciously archaic and dense style has put off some modern readers, but many also find the literary style part of the attraction and consistent with his view of the universe as unfeeling and indifferent. Johnson, noting that Lovecraft despised seafood, “felt the ocean was sinister and foreboding. He reasoned that what frightened him would frighten and fascinate his readers, and he was right.” Asked to explain Lovecraft’s appeal, Johnson said, “He brought his own nightmares onto the printed page. He was a truly haunted mind despite his sense of the objective and the rational.” Broadbent said, “Lovecraft’s style, what he wrote about – horror, fantasy, science fiction, isolation and alienation, gothic literature – he combined that with a whole new aesthetic.” Rutherford said, “Lovecraft becomes pop culture at this point, no longer a rarefied taste,” citing the plethora of cinematic films based on his fiction. “He appeals to the Transcendental in me, the same thing that makes me love Whitman and Rilke.”

Asked to suggest an excerpt that best captured his sense of Lovecraft, Rutherford chose this stanza from his “At Lovecraft’s Grave,” written for the 50th anniversary ceremony:

We smile,

keeping our secret of secrets,

how we are the gentle ones,

how terror

is our tightrope over life,

how we alone

can comprehend

the smile behind the skull.

The author thanks Kyon Piche for research assistance.

Further information:

Rutherford’s Whipporwill Road: The Supernatural Poems: poetspress.org/reaper_catalog.shtml

Lovecraft Eternal group: facebook.com/groups/331924010190535

Lovecraft Bronze Bust Project: facebook.com/LovecraftBronzeBustProject