Our cover artistically renders bullet holes as if this magazine has been shot through with a gun, motivated by the fatal but accidental shooting of William Parsons, a 15 year-old Central High School student who was waiting to be picked up outside another nearby city high school, the Providence Career and Technical Academy. By all accounts, the victim was an innocent bystander struck by a bullet fired by a 16-year-old boy, not a student, who had become involved in a conflict on the street or sidewalk.

Understandably, it is scary to hear not only that a 15-year-old was shot to death by a 16-year-old, but that it was a random consequence: any one of us, or our children, could have been killed standing in precisely the wrong place at precisely the wrong time. We all know intellectually that this is true, whether that bolt out of the blue comes in the form of a bullet or a heart attack, but there is an emotional resonance when we not only see it happen to somebody, but see it on television and in the newspapers. There is no denying that this death was a horrible tragedy.

(Photo: Michael Bilow)

Is there a “climate of violence” that threatens all children, forcing them into a premature loss of innocence where they become so fearful of and stressed by the risk of death that they cannot learn in school or do other things we expect of children? Insofar as there is, it is an artificial consequence of the attention we – society generally and the media specifically – shower upon these exceedingly rare and unlikely events. Children are threatened every day, but the chance of being randomly gunned down is infinitesimal compared to those other far more common risks: malnutrition, poverty, homelessness, lousy schools, incapable parents. If we restrict our list to causes of risk of physical death, shockingly ordinary factors, such as fire and drowning, kill far more children than intentional violence. If we further restrict our list to causes of risk of physical death from intentional violence, what puts the most children at risk are abusive family situations – because nearly all violence is not random – and the decisions some young people make to become involved in gangs and drugs. Emotionally upsetting incidents, such as the death of an innocent bystander hit by a stray bullet, can cause dangerously misguided mistakes of public policy where effort is invested in preventing rare and unlikely threats instead of common and fairly well-understood threats. There is exactly zero likelihood of confiscating every gun from every teenage gang member in the city, and merely making the attempt would require fascistic infringements of civil liberties, but there is a very good likelihood, if we make the appropriate logistic and financial commitment, of making sure every child in the city is properly fed and housed.

Human beings are lousy at recognizing the statistical insignificance of their own experience, and that error breeds fear – unnecessary fear, because it is, for all practical purposes, fear of the unreal. The objective truth is that Providence is a very safe city in a very safe state: it is an urban capital at the center of a metropolitan area of about 1.6 million, the 38th most populous in the country. How big is that? We’re bigger than Milwaukee (39th), Memphis (42nd), Raleigh (43rd), Richmond (44th), and even New Orleans (46th). But how likely are you to be a random victim of street violence?

In 2016, the most recent year for which the FBI has released complete data, there were 29 murders in the entire State of Rhode Island, of which 12 – fewer than half – were committed with a firearm; the other weapons were knives (9), non-traditional weapons such as a “blunt instrument” (6), and hands, fists, and feet (2). By comparison, according to the RI Department of Health the death toll in RI during 2016 from drug overdose was 336, part of what the federal Centers for Disease Control call the broader class of “accidents” that accounted for 675 deaths, and even these numbers pale in comparison to the 2,256 deaths from heart disease and 2,171 deaths from cancer in RI in 2016. Why didn’t we put a cigarette on our cover instead of bullet holes, given that cigarettes are known to cause heart disease and cancer? Are we less afraid of the long, slow, painful death typically caused by cigarettes than of the sudden death caused by a bullet?

(Compiled: Michael Bilow)

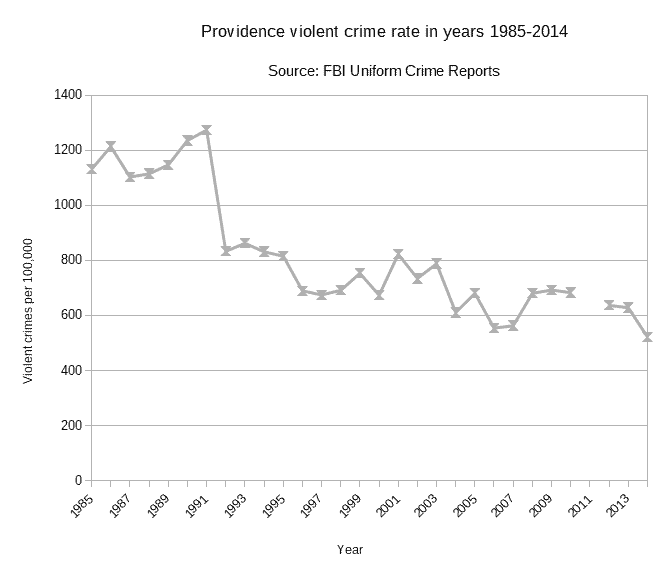

Providence is not only safe, but has been getting consistently safer for the past 25 years. Murder is so rare in RI that tiny variations year-to-year can cause unduly large swings in the rate, so it is more instructive to look at the rates for violent crime generally to get a more accurate picture of how safe someone can expect to be. The violent crime rate per 100,000 population exceeded 1,100 every year from 1985 to 1991 and exceeded 1,200 in three of those years (1986, 1990, 1991). In 1990, there were 31 intentional homicides just in Providence alone. Steady improvement brought the violent crime rate down to 522 by 2014, the most recent year available – a decline to less than half in about 25 years. By comparison with comparably-sized municipalities in Massachusetts, in 2014 the violent crime rate in Worcester was 965 and in Springfield was 1,091. Some big cities are even more unsafe: in 2014 the violent crime rate in Washington, DC, was 1,185, in Baltimore was 1,339, and in Detroit was 1,990. Some big cities that are relatively safe are still more dangerous than Providence, and even in Boston the violent crime rate in 2014 was 726.

How worried should you be about the 0.00275% statistical probability (using 2016 data) you have of being a murder victim in RI? Sure, you can look around the room at 36,500 of your closest RI friends and assume that one of them is likely to be murdered within the next year, but murder and crime don’t work that way: murder is not uniformly distributed across the population, and instead some people are far more likely to be murder victims than others. The largest cohort likely to be shot to death by another are young men under the age of 35, which is a fairly good statistical proxy for those involved in criminal activity such as drugs and gangs. The next largest cohort likely to be shot to death by another are people (both men and women) in abusive domestic relationships.

William Parsons, as difficult it may be to accept, was simply an extremely unlucky young man. His death at age 15 is not an indicator or warning of some systemic problem in our society involving either guns or schools. Why the unnamed killer felt it necessary to carry a handgun in the first place remains unknown, especially with much of the case sealed because of his status as a juvenile, but it seems a reasonable inference that whatever threat he worried about was a result of his engaging in criminal activity and interacting with other criminals: he is reputed to be a member of the Hanover Boyz street gang. This was not a “school shooting” although it happened by chance outside a school. No realistic change in gun law or policy could prevent a 16-year-old already enmeshed in serious crime from obtaining a gun that it was already illegal for him to possess.

Our shot-up cover was chosen at our editorial meeting because it was “dramatic” and “impactful” – which it is, but it’s also, in my opinion, misleading because Providence and its city schools are not a shooting gallery. We’re just doing it to emotionally manipulate and lie to you. Did it work?

More Posts by The Author:

Universal Basic Income and the Future of Work: Ominous Portents

News Analysis — Secret Police Records, Secret Arrests, Secret Charges: Brown University police make every effort to escape public scrutiny and accountability

Defending the Electoral College

Halloween 2024 Weather Forecast: Unusually warm but ideal for trick-or-treat

Cannabis Status: Update on expungements, taxes