After Everything Burns … there’s The Man at The Door. He will be standing there in the night holding a cactus to his chest.

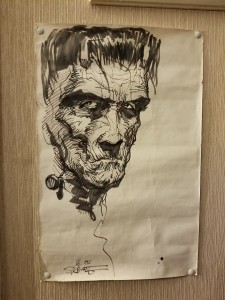

After Everything Burns … there’s The Man at The Door. He will be standing there in the night holding a cactus to his chest. I recently met with rebel poet, poetry slam badass and all around fungi to be around, Mr. Ryk McIntyre, at his batcave in Cranston. It was a cold night, and it had just started to snow. There were predictions of blizzard conditions and something about a Polar Vortex. Ryk welcomed me into his laboratory and bade me to sit down on what I think I remember was some cool, stool-like object (could have been a crate). I was trying not to look around too much. I knew I could get engrossed in any number of interesting objects and books all around on shelves. When you’re welcomed into a poet’s den for an interview, you must take care not to distract yourself by all the interesting things around you. Oh, he has THAT book. What is that crazy looking thing? Omigodisthatahumanfoot…? Cool, Frankenstein drawing on the wall… Focus.

Tell me about you. Who are you? Where did you begin?

Ryk and his birth siblings (three sisters and a brother) were taken from their parents in the middle of the night for neglect. “And it must have been real bad because they didn’t really do that in 1963.”

After a series of foster homes and adoption centers, Ryk eventually was placed with the McIntyres at around age 3 and a half. The couple had been experiencing some marital issues and, as a means of helping with the relationship, perhaps, they became foster parents — each for different reasons, apparently. Three years later, the State of Massachusetts decided that the best place for children in state and foster care was back with their birth parents. Ryk’s mom, Carol, hired a lawyer and fought the state for the right to adopt him and won. Six years later, however, the couple separated. It was never his father’s plan to adopt him — fostering was fine when the state provided money for the children’s care. The adoption triggered fight after fight. The court-ordered visits with Ryk as a condition for visitation rights with his two sons by birth led to a very tenuous relationship between father and son. Ryk became “Carol’s kid” in his father’s eyes. Not really his responsibility. The stepkid.

Ryk was sent to boarding school for a year. In addition to the fact that the school didn’t work to straighten him out, somebody played Gil Scott Heron’s “The Revolution Will Not Be Televised” and his head exploded. No, not literally. But his life changed forever in that moment. You can do this with poetry? Similar moments with Bob Dylan and Patti Smith led the young man to develop an appreciation for work that challenged the conventional ideas of poetry and how lyrics could be presented. Patti Smith and Jim Carroll made poetry cool again. Here were poets not being told what poetry is. Not making poetry behind polite podiums, they were turning their poetry into rock and roll. Making it Real.

Didn’t you used to belong to a band or something?

Ryk describes himself as having been a “fan of a couple bands.” While the drummer would set up, young Ryk would share his brand of spoken word with the waiting audience. “When I first got on the stage and shared my words in between drum setups, I expected bottles to be thrown at me.”

But the response was overwhelmingly positive. A poet is born. Sometimes a monster is your friend. Sometimes the shadows don’t bend enough to let a sliver of moonlight in. So you tug at the seams in your skin suit and howl at the empty sky until a hole opens up in you … or it. Sometimes they will tell you that you have split personalities or that your abnormalities are a smorgasbord of circumstantial haberdashery. But you cling to your cactus and squeeze until you find liquid either in your palms or in its bitter leaves.

The desegregation of Boston public schools (1974–1988) was a traumatic period in which the Boston Public Schools were under court control to desegregate through a system of busing students from one area to another. It primarily affected the poor residents from the Italian, Irish and black communities in Boston. Many people were injured in many spates of violence, buildings were burned and the Boston school committee defied the order at every turn, as people fought not to be integrated. When the busing came to Wellesley, the reception was less than warm.

Ryk recollects his first engagement with Parliament Funkadelic at this time. He exchanged mixtapes with another student, a black student from the METCO program. Although Ryk only gave him a copy of Queen’s album (an unfair trade he has laments in hindsight), he counts this cultural exchange as a major influence on his life and his poetry.

The arrival of inner city black kids to Wellesley was not as widely welcomed as Ryk’s musical exchange would have it seem. The year after he graduated, there was a “near riot” at his high school.

His poem “Kissing in Wellesley” describes a moment of adolescence where he was being persecuted for having had a lip lock with a dark-skinned young lady he met at a church youth event.

I look back at the picture on the wall. Frankenstein. Done in pen. The entire time we interviewed I kept glancing at the oh so intriguing drawing on the wall, and I began to see some similarities. And suddenly it hit me. To have had so traumatic a beginning: ripped from his parents home at such a tender age, rescued but without a home, changing spaces and teachers, eventually finding home and then losing that home. Divorces and bad relationships. Alcohol and drug abuse. Depression and chronic pain … all this can make a person feel ugly and without purpose. The man is a veritable Frankenstein of life events.

Ryk has been through the wringer, and his poems (some seven books deep) reflect some of that chaos and turmoil with an eloquence and artistry that reminds us that the duty of a poet is to illuminate the mundane and the commonplace and elevate them to things of beauty. It is as if Ryk went into the mirror to find his true self and stole something on his way back out.

This drawing, showing a very Ryk-like Frankenstein, glancing at the viewer with a semi-scowl and a tight lipped non-grin, represents my host very much as a metaphor. We are all monsters. But sometimes a monster can be a beautiful thing.

Ryk is today a father of three and has been sober for five and a half years. He has returned to college at age 54 and is pursuing his associate’s degree in liberal arts: English at one of RI’s fine colleges. Later, he will use his Phi Theta Kappa honors society membership to pursue a BA in creative writing/performance. His two books, After Everything Burns (2013 Sargent Press) and Man at the Door (2018 Broken Head Press) are available on Google Books. If you see him, ask him to kick that Godzilla Rap, for old time’s sake.