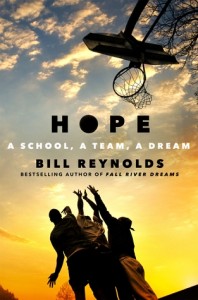

Bill Reynolds, long-trusted sports columnist for The Providence Journal, has great talent for finding teen athletes in Rhode Island, recognizing not only their athleticism but also the life obstacles they have hurdled, and spreading their story in order that they may receive the recognition they have earned. He has transferred the energy and heart with which he writes these articles to his book, Hope: A School, A Team, A Dream.

Bill Reynolds, long-trusted sports columnist for The Providence Journal, has great talent for finding teen athletes in Rhode Island, recognizing not only their athleticism but also the life obstacles they have hurdled, and spreading their story in order that they may receive the recognition they have earned. He has transferred the energy and heart with which he writes these articles to his book, Hope: A School, A Team, A Dream.

Throughout the 2012 season, Reynolds follows the basketball team of Hope High School – a school known for its fierce basketball team, but also for fights, empty desks and racial tension. Even with the advice and support of head Coach Nyblom, who has been coaching at the school for 24 years, it’s not easy for these boys to persevere through Hope. And this side of Providence is what Reynolds captures with his reporter’s eye: Hope is not Friday Night Lights; it is a blunt report of the lives and dreams that too often go unnoticed in inner-city Providence.

Often, when introducing an athlete or a coach, Reynolds gives a few paragraphs of explanation as to how they got to where they are. And while of course no two lives are the same, these stories follow similar patterns of hope and apathy, distant fathers and gang violence, school reforms and despairing teachers, and, in this case, fighting it all to grasp the basketball dream. In particular, the coaches’ memories of a more peaceful Providence and a functional Hope High School often launch Reynolds into a history of the school and how it has changed due to bussing, the end of vocational courses, a muddle of other politics and lack of faith in the children. Reynolds gives a face to state and even national history, and his skill in reporting and analyzing facts adds depth to the work.

The book lacks a bit of style only on occasion, when Reynolds tries to be whimsical. The similes he uses sometimes feel random and disconnected, and they may have had more poignancy, and thus the book more vibrancy, if he had kept a continuous theme. He does best when straightforwardly describing the people we meet and the whirlwind games they play, and when riding the school bus with the athletes and seating the reader next to him, whether that’s by interacting with the players or by giving us an historical tour of Providence through the buildings he sees out the window.

Now, as with many a sportsbook, Super Bowl Sunday, and March Madness, you, dear reader, are perhaps saying to yourself, “The spirit of it is nice, but I have no idea what goes on in this game.” Well luckily (and I speak from experience), Reynolds does not use the jargon one might expect from a sports reporter. Instead, he relates the tenor of the game and mood of the players (things that often play a larger role than the organization of the team in whether they win or lose). This tactic of Reynolds’ also helps the reader get to know the athletes.

Speaking of getting to know the athletes, a review of Hope by Publishers Weekly claims that “Reynolds says he cares for Hope’s players, but he never shows it” in part because he “rarely follows the kids beyond the gym.” But Reynolds often does attempt to strike up conversations with the athletes before practice, on the bus to games and (a few times) while giving them rides home. But it’s clear that often, the athletes emotionally close themselves off, even from their coaches. Even, for example, when senior Emmanuel “Manny” Kargbo does talk to Reynolds about “problems” at home, he keeps it vague, and immediately adds: “But I can’t be yelling at my teammates…I have to be a leader.” The private lives of teenagers, especially when it comes to published material, are just that — private.

I would recommend this book to social workers, but only because they are passionate about helping these teens, not because they need to pull rosy glasses off their eyes — they’ve heard similar stories only too often. On the other hand, politicians and many of the students (especially those from out of state) attending the elite colleges in Rhode Island could both benefit from the testimonies in Hope: In one of his historical excursions, Reynolds relates that students protested the abolition of the block scheduling system, which had worked well, by marching to City Hall, and were ignored, “supposedly so all the public high schools in the city would be uniform” in regard to scheduling. And just as the students on Hope’s basketball team don’t know that they walk past Brown every day, most students at elite Rhode Island colleges don’t know what invisible barriers stand a block away.