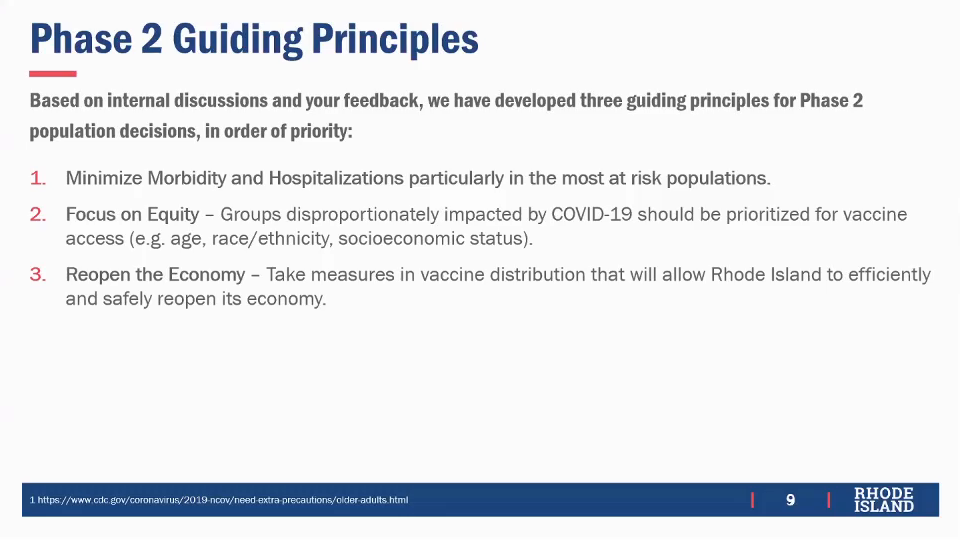

How to define eligibility for priority groups in Phase 2 of the state COVID-19 vaccination program was the subject of the regular weekly meeting of the Vaccine Sub-Committee at the RI Department of Health (DoH) on Friday, January 22. The goal is to have this clearly settled by the time Phase 2 is expected to begin in late March or early April.

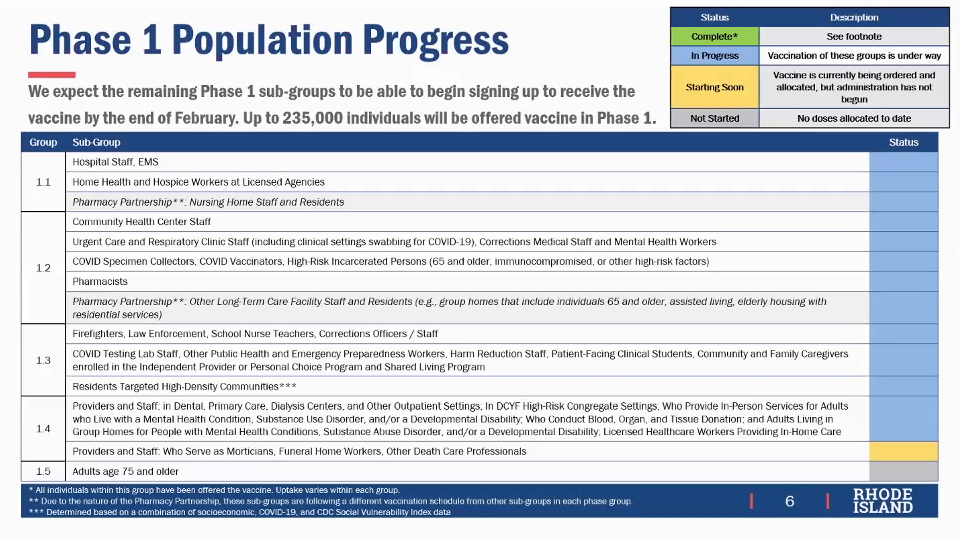

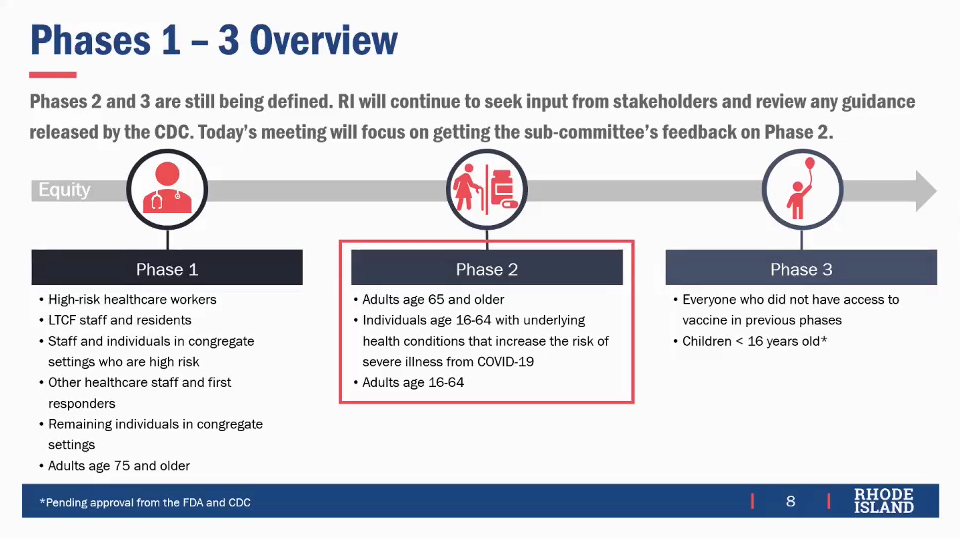

The supply of vaccine, currently about 14,000 doses per week, is not expected to increase for the foreseeable future, Alysia Mihalakos of DoH told the sub-committee. Phase 1 began in December with the most high-risk groups, frontline health care providers and nursing home residents and staff in Phase 1.1, moved on to frontline professionals in critical infrastructure such as firefighters and law enforcement in Phase 1.3, and will conclude with all persons 75 years of age or older in Phase 1.5.

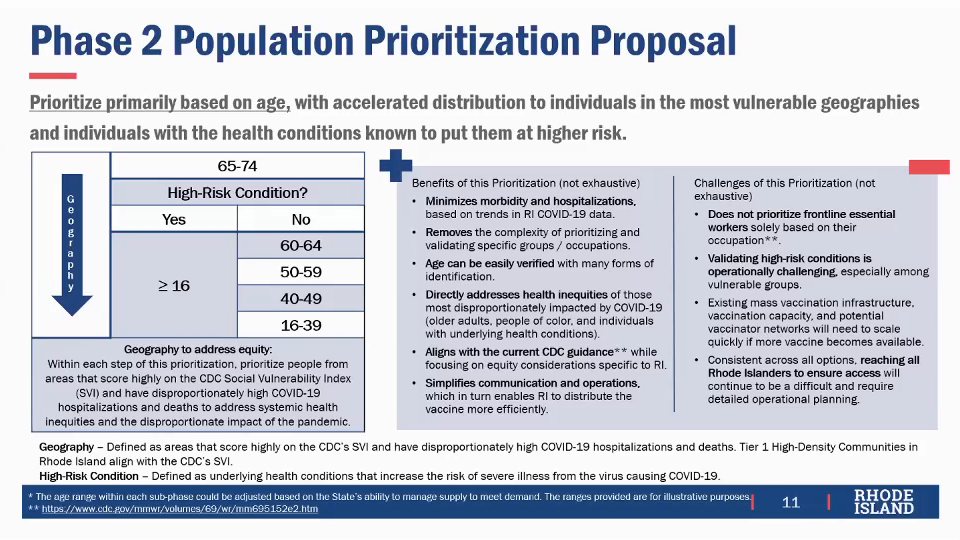

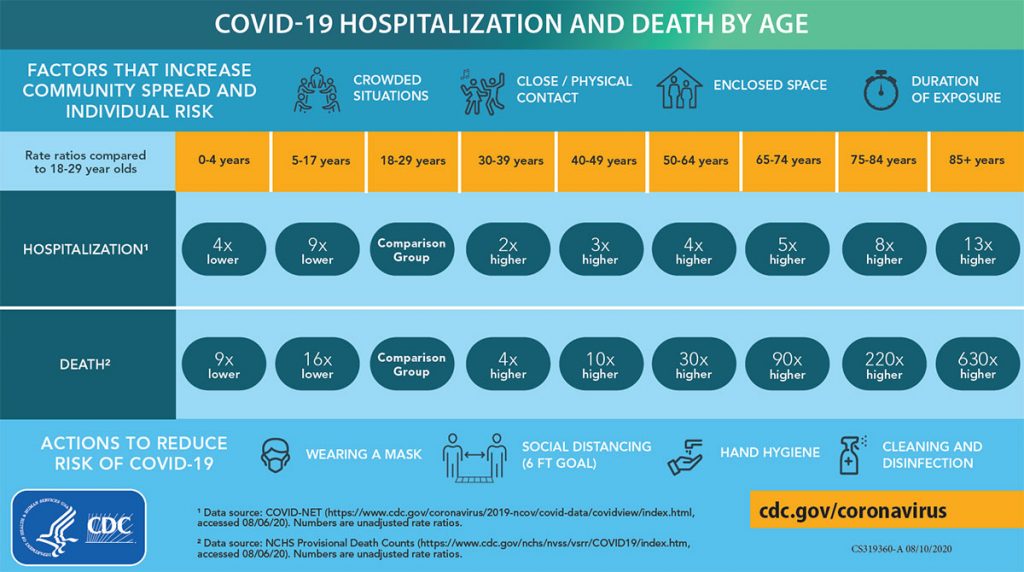

The main challenge, according to meeting facilitator Mckenzie Morton, is to specify eligibility criteria that can be “operationalized,” meaning that the state can readily deploy resources in accordance to match and verify eligibility. As a result, the principal criterion proposed is age, which is known to correspond to risk of hospitalization and death, so that Phase 2 would begin with all persons age 65 or older. After that, all adults with medical conditions that put them at high risk would become immediately eligible, and other adults without such medical conditions become sequentially eligible by age strata 60-64, 50-59, 40-49, and finally 16-39.

No vaccine is yet approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for persons younger than 16 because clinical trials are still in progress, so there is as yet no data on safety and efficacy. As of last week, a national trial had recruited 800 of a needed 3,000 volunteer test subjects ages 12 to 17.

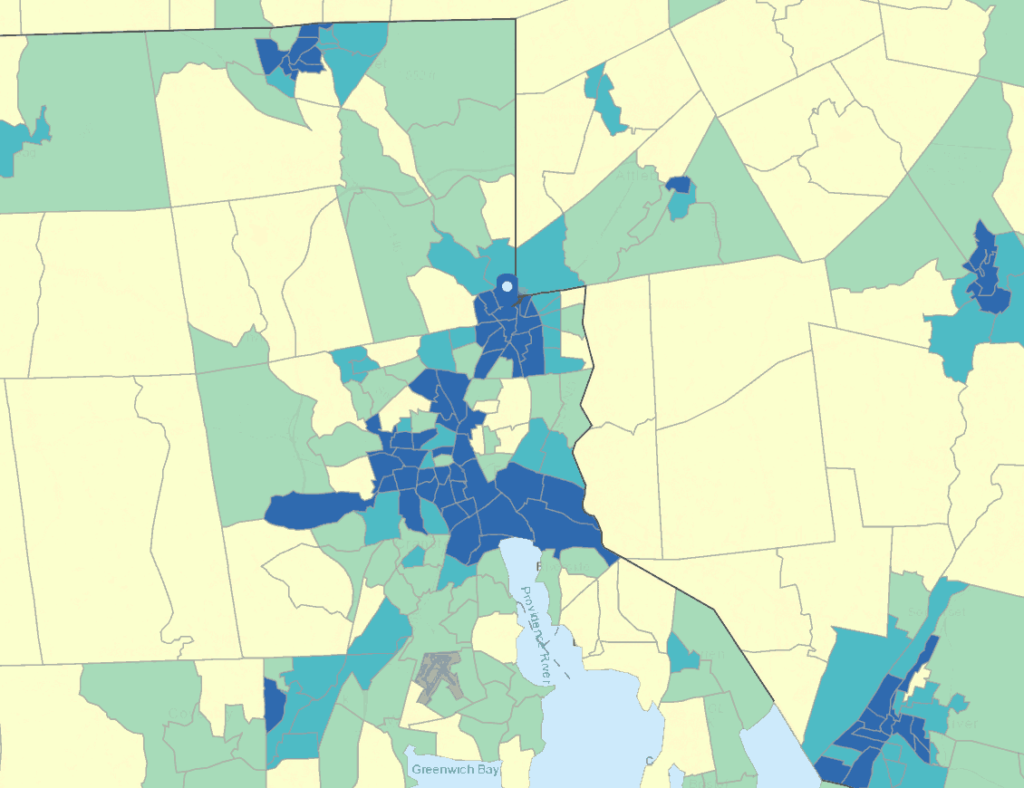

Although age can be checked with commonly available identity documents, geography is also known to correlate with greater risk of infection, and the proposal is to prioritize in part using the Social Vulnerability Index (SVI) published by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) that measures “potential negative effects on communities caused by external stresses on human health” with census tract granularity. Exactly how “geography” would be defined for vaccination was not discussed, leaving open such questions as, for example, how a teacher who works in Central Falls and lives in Exeter would be classified.

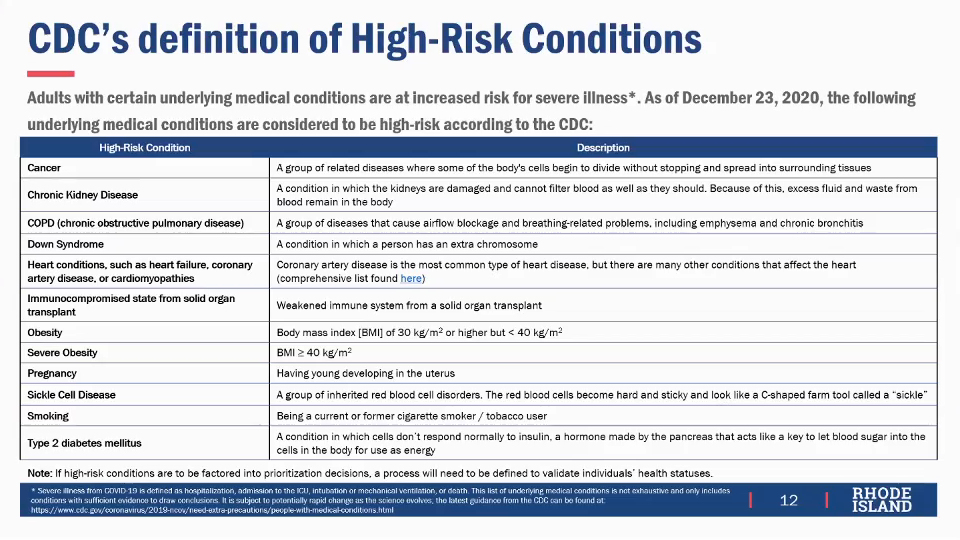

Although the CDC lists medical conditions known to be associated with increased risk of hospitalization and death from COVID-19, several sub-committee members pointed out problems with the CDC list. Relatively rare conditions, such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), which is commonly called Lou Gehrig’s disease, and Ehlers–Danlos syndrome, probably did not make the list only because of their rarity. It was observed that other conditions on the CDC list may be secondary in risk, such as Down syndrome that is often correlated with heart disease that is also on the CDC list. It was also suggested that substance abuse disorders can result in severe alcohol disease such as cirrhosis, which would put a patient at high risk, but this is not on the CDC list although a history of smoking is on the list. Mental health disorders can result in patients being unable to access reliable physical health care, putting them at higher risk from COVID-19 and also presenting difficulties in making sure they receive a required second dose of vaccine after the first.

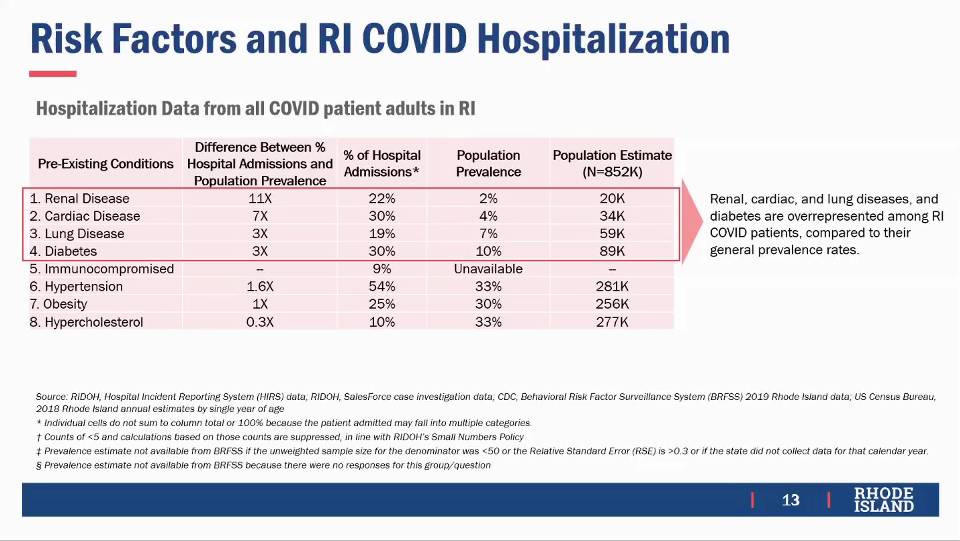

Some conditions listed as high-risk by the CDC are so common that they provide little help in prioritizing vaccination, such as high blood pressure, high cholesterol, and obesity that each affect over 30% of the entire population of RI. Nor are such conditions grossly disproportionately reflected in hospital admissions: obesity is present in 25% of hospital admissions for COVID-19 in RI, less than its 30% prevalence. As a result, the proposal focuses on four specific conditions of known prevalence that account for a disproportionate number of hospital admissions in RI at least triple their prevalence: renal disease (22% of admissions, 2%/20,000 prevalence), cardiac disease (30% of admissions, 4%/34,000 prevalence), lung disease (19% of admissions, 7%/59,000 prevalence), and diabetes (30% of admissions, 10%/89,000 prevalence). The proposal also includes those who are immuno-compromised, either because of another medical condition such as HIV positivity or because they are on suppressive drugs as would be the case for organ transplant recipients, accounting for 9% of admissions but of unknown prevalence. (Some patients have more than one condition.)

While there was some concern about people claiming to have high-risk conditions due to anxiety to be vaccinated, DoH Director Nicole Alexander-Scott said that her preference was to follow a “self-attestation” model, essentially putting people on the honor system, especially because the eventual goal is to vaccinate everybody. If there are too many barriers requiring proof of eligibility, the concern is not only would this discourage people in legitimate medical need, but would likely disproportionately discourage the most vulnerable who may not even have a primary care practitioner (PCP).

Consistent with the frequently emphasized goal of equity, several members of the sub-committee raised the concern that COVID-19 has radically disparate effects by race and ethnicity, citing as an example a study that showed infected Black patients in their 50s have a risk of death comparable to those in their 70s among the general population. Rather than take race into account explicitly, the proposal intends the combination of geography and medical conditions to subsume race, as these factors are believed to be significant likely causes of racial disparity in health outcomes.

The proposal avoids distinguishing by occupation in Phase 2, which would be operationally difficult as well as requiring selections among, for example, teachers and grocery store workers, effectively putting different occupations in competition with each other for vaccine. Alexander-Scott said that more than half of teachers would qualify based upon age and medical condition alone, even before taking geography into account, reducing the need to prioritize teachers specifically. Jonathan Brice, a school superintendent representing educational interests, said that he would prioritize teachers who work with students unable practice mask wearing and physical distancing, either because they are very young, in his example kindergarten through second grade, or because they have special needs. It is possible that the federal government may make additional vaccine supply available and earmark it for specific groups such as teachers, Mihalakos said, but at this point there is nothing definite.

One of the main advantages to the proposed structure for Phase 2 is that it would allow communicating to the public approximately when any given adult could expect to be vaccinated, based upon the known supply of doses, one of the most frequently asked questions to DoH, Mihalakos said. If the supply increased, as is expected from additional vaccines being authorized by the FDA and greater production of vaccines already approved, it would be simple to recalculate the improved time estimate.

The final Phase 3 would cover children younger than 16 and all others not previously vaccinated.