How deadly is COVID-19? How does it compare to seasonal flu? These are difficult and controversial questions.

Above all, it should be emphasized that some sub-populations are definitely at much higher risk for bad outcomes if they become infected, such as people with compromised immune systems due to existing underlying illness or simply old age. It should also be understood that some patients are extremely unlucky even if they are part of an otherwise low-risk sub-population, such as young people who contract rare multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) that appears to be correlated with COVID-19 in ways that are not yet understood.

Speaking in terms of broadly aggregated data, however, it is possible eight months into the pandemic to draw some conclusions based upon actual measurements, even if the measurements themselves and the resulting conclusions have large uncertainties. The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) on July 10 switched from reporting case-fatality rates (CFR) to infection-fatality rates (IFR): setting aside whether this was the result of political pressure, in general the difference is that the CFR is based upon cases diagnosed while the IFR is based upon cases both diagnosed and undiagnosed. In the context of COVID-19, this is important because people who have either no symptoms or such mild symptoms that they do not even know they are infected count in the IFR but not the CFR calculation. Obviously, it is very difficult to count undiagnosed cases, so estimating them depends upon trying to measure what proportion of infections are so mild as to go unnoticed and extrapolate from surveillance testing of people without symptoms.

The CDC performs meta-analysis on data and studies, resulting in several scenarios that they think are most likely to represent reality. Unfortunately, their estimate of undiagnosed (asymptomatic) cases ranges as low as 10% to as high as 70% with a “best estimate” of 40% of total cases, an enormous amount of variation. The larger one believes the number of undiagnosed cases to be, the lower the IFR for a given number of deaths as a purely mathematical consequence.

On the other side of the fraction line, one would think counting deaths would be easy, but it’s not. The CDC counts COVID-19 fatalities weekly, although delays in reporting from a multitude of local jurisdictions with widely varying clerical practices and resources can introduce weeks of delay, but as of August 22 their number was 164,280. Despite its faults, this is the best hard number available; it’s a lower bound.

There is the matter of definition: What is a COVID-19 related death? The CDC has clear rules on that, but again there is room for disagreement on their appropriateness. Certainly if you test positive for COVID-19 and die of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), gasping for breath on a mechanical ventilator, everyone would agree to attribute your death to COVID-19. But what if you test positive for COVID-19 and die of something else that is plausibly related to COVID-19, such as a heart attack or ischemic stroke that you probably would not have had but for the stress on your body of fighting COVID-19? What if you died from a heart attack or stroke, although you’re not infected by COVID-19, but you decided not to go to the hospital because you were afraid of COVID-19? What if you had symptoms of COVID-19 but chose to stay at home, were never tested nor treated, and died there?

One way to capture this complexity is to look at the number of “excess deaths,” the number of deaths above what would have been statistically expected based upon past experience. For the week ending April 18, the US had about 38% more deaths than expected, 77,086 instead of the expected 55,683. That was a very bad week, but the concept encapsulates the key idea: How many people died that week who would not have died without the pandemic? As a practical matter, this is what the ordinary person means when they ask that original question: How deadly is COVID-19? How many deaths are we under-counting?

But excess deaths is too broad a category for public health experts to use for effective planning. What they want to know is not “How many people died because of COVID-19?” but rather “How many people died because they were infected with COVID-19?” This is where those previously mentioned hypothetical CDC scenarios come into play, with the IFR between 0.5% and 0.8%, and a “best estimate” of 0.65%. These IFR numbers may seem low, but this is merely a mathematical consequence of the number of undiagnosed cases being high.

And the United States is very big. How big? The total population is about 330 million, so that 0.65% IFR implies, if 100% became infected then the death toll would be over 2.1 million people! That is presumably a worst-case upper-bound scenario: If physical distancing, mask wearing, hand-washing, and other methods prevent infection in the first place, that would save a lot of lives, possibly millions of lives, and delay the spread of the virus until a vaccine can be made and distributed.

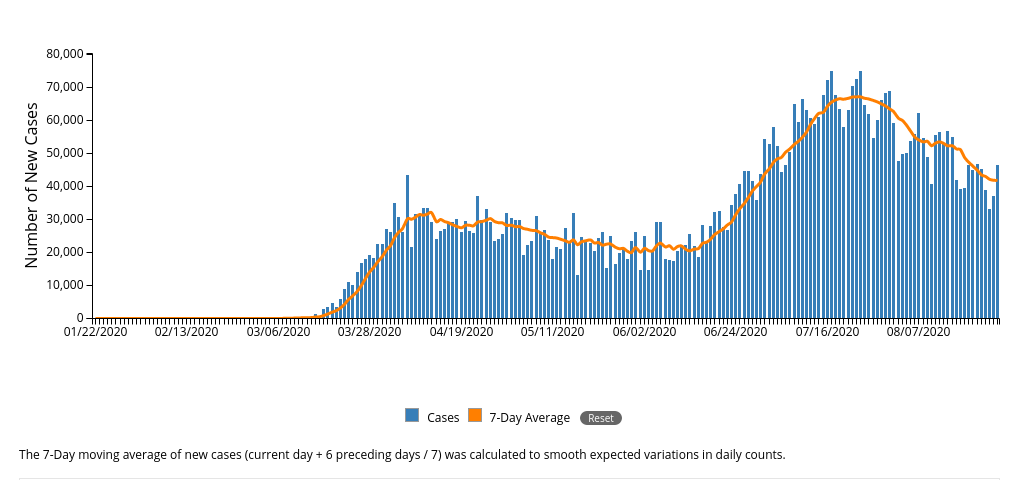

As I write this in the late afternoon of August 27, the CDC data release at 4pm today estimates a cumulative total through yesterday of 5,799,046 diagnosed cases, of which 46,393 new cases occurred yesterday, and a cumulative total through yesterday of 178,998 deaths, of which 1,239 new deaths occurred yesterday. Seasonal flu was not killing well over a thousand Americans daily. By the way, that works out to a CFR of 3.1% in the US, which might be why the CDC was under pressure to replace it with the more speculative IFR. A CFR about 3.1% would put COVID-19 into the same league as the 1918 pandemic that killed 50-100 million worldwide: contrary to intuitive expectation, a virus in order to continue to spread to kill a maximum number has to avoid killing its hosts too effectively, and 3% seems to be the sweet spot. The widely respected COVID-19 tracker at Johns Hopkins University currently shows 24,284,974 cases and 828,041 deaths worldwide, a CFR of 3.4%; among all countries the US is in the dubious first place in both categories, well ahead of second-place Brazil.

How much worse is COVID-19 than seasonal flu? In the October 2019 to April 2020 flu season, there were 24,000-62,000 deaths from 39-56 million symptomatic infections, implying a CFR of 0.1%, roughly 30 times lower than the 3.1% of COVID-19. But people have residual immunity to seasonal flu from prior exposure to similar strains, there is a vaccine that about half of adults get, and there are proven treatments for those infected – none of which is true of COVID-19 – so the spread of seasonal flu is inherently limited.

If your COVID-19 is bad enough to put you in the hospital, outcomes grow quickly much worse: 11.7% of hospitalized patients age 11-49, 21.8% age 50-64, and 21.3% age 65 or above will need a mechanical ventilator; 2.0% of hospitalized patients age 18-49, 9.8% age 50-64, and 28.1% age 65 or above will die. Well, that escalated quickly. So what are your chances of needing to be hospitalized? We know that from COVID-NET: as of the week ending August 15, 102.2 per 100,000 population age 18-49, 228.1 age 50-64, and 412.9 age 65 or more – so far.

None of this should be misunderstood as hopeless doom and gloom: instead, understanding the severity of COVID-19 should emphasize the critical importance of acting responsibly to observe public health recommendations proven to work: isolating if symptomatic, physical distancing, mask wearing, hand-washing, avoiding crowds. With more than 1,200 Americans dying daily, no one should mistake the virus for being under control, but we do know how to bring it under control.