At her daily press briefing on April 25, RI Gov. Gina Raimondo announced an arts initiative, inviting anyone in whatever medium to submit original family-friendly work on a new website RIarts.org created for that purpose.

The governor said that she contacted internationally renowned artist Shepard Fairey and asked him to help by creating a work that inspired hope. “I just called Shepard Fairey a month or so ago, a few weeks ago, I can’t remember now. He’s a RISD grad and he’s a very well known artist. It was kind of the depths of this, to be honest, and I thought everybody could use a little bit of hope, so I asked him if he would volunteer his services and create an image that he thought would be hopeful, and this is what he came up with, like he says, to celebrate the courage of healthcare workers specifically, and generally symbolize the spirit of hope, strength, compassion and resilience. It’s all his artistry and I thought, and I think, it’s beautiful. To me, in addition to the fact that it’s a symbol of hope and strength, I see it and I feel it’s just really a nod to all of our first responders and healthcare workers, and a big thank you from us to them. It reminds me a little of Rosie the Riveter.”

Fairey got his start as a student at RISD making guerrilla illustrations, most notably the “Andre the Giant Has a Posse” stickers created as a quick project in 1989, a seeming advertisement for nothing with no clear meaning that he sold for 10 cents each. The surreal incongruity of the “Andre” stickers caused them to appear everywhere, soon plastered on walls and street signs by admirers in many cities, participants in an anti-art mass in-joke subtly ridiculing the techniques and tropes of advertising: “Why does he need a posse, and why are you telling me?” Somewhere between Marcel Duchamp and Zen koan, “Andre” struck a nerve and became a memorable popular icon, widely recognized and frequently parodied. Beyond the community of artists (and sk8er bois) familiar with the “Andre” sticker, Fairey became far more well known in 2008 as the creator of the definitive campaign image of Barack Obama, the “Hope” poster.

While he was alive the actual André the Giant does not seem to have minded (nor even noticed) the attention from Fairey, but after his death in 1993 his estate demanded that Fairey stop selling anything referencing the trademarked professional wrestling character name, forcing Fairey to simplify and abstract the image to mostly just the eyes. Fairey labeled the new version with nothing more than the word “OBEY,” which became his new brand. In another nod to anti-commercialism, that is a reference to the 1988 John Carpenter horror film They Live, in which space aliens infiltrate human society and use a secret transmitter to brainwash people into being unaware of subliminal messages conveyed through advertising, and the hero obtains sunglasses with “Hoffman lenses” so he can see what is really happening, an allusion to Swiss chemist Albert Hofmann who discovered LSD. (Carpenter wrote the screenplay under the pseudonym “Frank Armitage” as an homage to H.P. Lovecraft’s consistent theme of the “hidden world.”) The film has since become a cult classic, with the aliens introducing climate change – remember, this was in 1988 – to warm the earth more like their natural habitat.

The governor said that Fairey immediately agreed to her request and designed the “Rhode Island Angel of Hope and Strength,” an obvious evocation of the Statue of Liberty: a winged woman holding a torch, dressed in medical garb with a red cross emblem. The RI Arts website quotes Fairey: “This piece was created to celebrate the courage of healthcare workers specifically, and generally symbolize the spirit of hope, strength, compassion and resilience that we can all find in ourselves and share collectively.” The governor told Motif that no money changed hands and the work is royalty-free for any use.

There is an uncanny resonance between Fairey’s most famous work, the Obama “Hope” poster, and the heraldic seal of the State of Rhode Island, a fouled anchor with the motto “Hope.” Seeking to found a bastion of religious freedom, the earliest settlers of Rhode Island were refugees of conscience escaping Massachusetts, and the seal (often mistaken for a nautical allusion) is a canting reference to the Epistle to the Hebrews 6:18-19 which, in the King James Version, describes those “…who have fled for refuge to lay hold upon the hope set before us: Which hope we have as an anchor of the soul, both sure and stedfast…”

There is enormous irony that Fairey, whose early work embraced anti-commercialism, now with his wife Amanda runs an advertising agency, Studio Number One, that draws a direct line from “Andre” to a client list including Coca-Cola, Pepsi, Disney, Paramount, Universal, Warner Brothers, Adidas and Nike: “What started for Fairey with an absurd sticker he created in 1989 while studying at the Rhode Island School of Design has since evolved into a worldwide street art campaign. Heidegger describes this as Phenomenology – ‘the process of letting things manifest themselves.’” Given that Martin Heidegger is primarily remembered today as one of the most influential intellectuals of the 20th century who tragically manifested himself as an ardent Nazi, one suspects Fairey intends this as yet another joke.

In a revealing interview conducted by Chris Nieratko of International Tattoo Magazine in 1999, a decade before the Obama poster would make his work instantly recognizable, Fairey discussed that. “I always want to maintain the sense of humor in it all. I think it’s real important that people can see the humor in everything. And even though some people don’t see the humor in the Stalin graphics or the Lenin graphics, people need to realize they are not serious. You can’t insert obey giant’s face next to that of a communist leader and hope that people pull the message, ‘Communist, dead wrestlers should take over the world.’ There are those people that take it that way, that have such a knee-jerk reaction to the colors that they automatically think it’s negative. What’s so ironic though is that they are assaulted, bombarded with Marlboro using the same colors as l am, but they don’t get uptight over that. They should fear Marlboro way more than a dead wrestler, that’s for sure. What I’m doing now is making fun of propaganda and advertising utilizing the same devices at the same time.”

Right on cue two decades later, on Apr 28 the conservative research and advocacy group RI Center for Freedom and Prosperity issued a statement condemning Fairey’s angel as “a bastardization of the Statue of Liberty wearing a communist China-type cap and tunic, in a layout reminiscent of posters supporting fascist dictatorships of the past,” showing it flanked by early 20th Century fascist posters of Stalin, Hitler, and a figure representing Mussolini’s Italy, all with arms upraised in a similar pose. That’s a bizarre criticism, as Fairey’s female figure is wearing a nursing cap, complete with stripe, used since the 1800s as a formal part of the uniform to identify the educational pedigree of the wearer, each nursing school having its own distinctive cap. As anti-communist as one can get, the original inspiration for the nursing cap invented by Florence Nightingale was the nun’s habit, and to this day in British Commonwealth English it is common to describe a medical nurse, regardless of religious affiliation or lack thereof, as a “nursing sister.”

A human figure with an arm upraised holding a source of light is hardly new, and it is very common in art. The Statue of Liberty itself was designed around 1870 and dedicated in 1886. An 1,800-year-old statue of Zeus found in Smyrna can now be seen in the Louvre Museum in Paris after a restoration in the 1600s gave it an upraised arm holding a lightning bolt.

Even more galling, the simplistic artistic style favored by Stalin and Hitler, intended by them to make art uncomplicated and accessible to the average person, had been perfected by Americans in the 1800s not because of authoritarian forces of government but by the democratic impulses of commercialism. Currier and Ives, founded in 1857, advertised itself as “Publishers of Cheap and Popular Prints,” introducing Americans to mass-produced wall art sold for as little as 5 cents, printed by lithographic presses and then hand-colored by low-skill workers. Indeed, the firm published an artistic rendering of what the Statue of Liberty would look like a year before it was constructed.

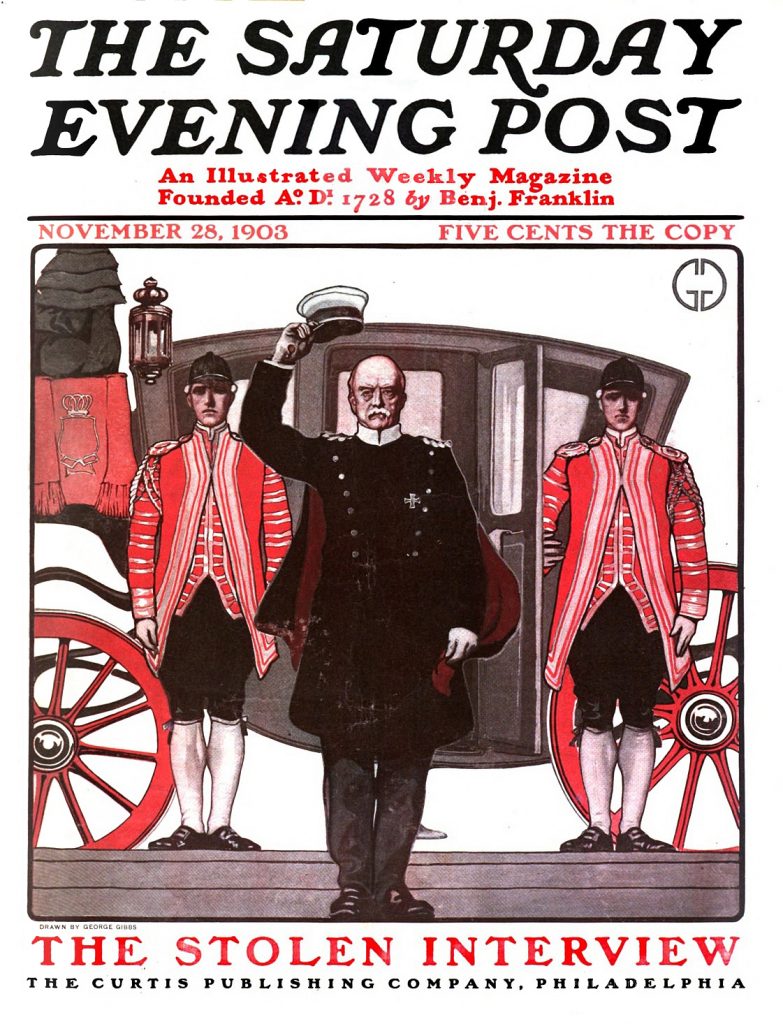

This style of American illustration arguably reached its pinnacle in The Saturday Evening Post, a weekly magazine founded in 1897 that made a household name of Norman Rockwell and used the work of many other famous American illustrators including J.C. Leyendecker and N.C. Wyeth; a 1903 cover by George Gibbs shows the late German chancellor, Otto von Bismarck, with his right arm upraised (holding his hat) in the red and black color scheme that Fairey describes as characteristic of Marlboro ads.

The RI Center for Freedom and Prosperity statement also alleged the image “is nothing more than a slight modification of a prior work,” but Gov. Raimondo’s office confirmed to Motif the situation was the reverse: the original was made for RI but its public release was delayed at the request of the governor to coincide with the announcement of her arts initiative on Apr 25, while in the meantime Fairey asked for permission to adapt it to a more generic version for Amplifier.org that was released on Apr 10, the dates ordering giving the mistaken impression that RI got a knock-off.

On the day the governor released the Fairey image, she was asked by a reporter whether the young female figure, perceived as white, was unrepresentative of those of color, men and older. The governor defended the image: “First of all, I don’t know that you know that she’s white. It’s an image, and it’s a black and white and red thing. It’s art: you can look into it whatever you want to see. By the way, if somebody wanted to do another image, that’s exactly why I launched the whole other website. Hopefully other people will put up other images and that would be great.”

One need not like Fairey’s work, but asserting that it is somehow “a symbol of communist and fascist totalitarianism,” when it looks at least as much like The Saturday Evening Post or a Marlboro ad, is criticism grounded in plain ignorance of art history.