Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this piece are those of the artist and not necessarily those of Motif, other writers or staff.

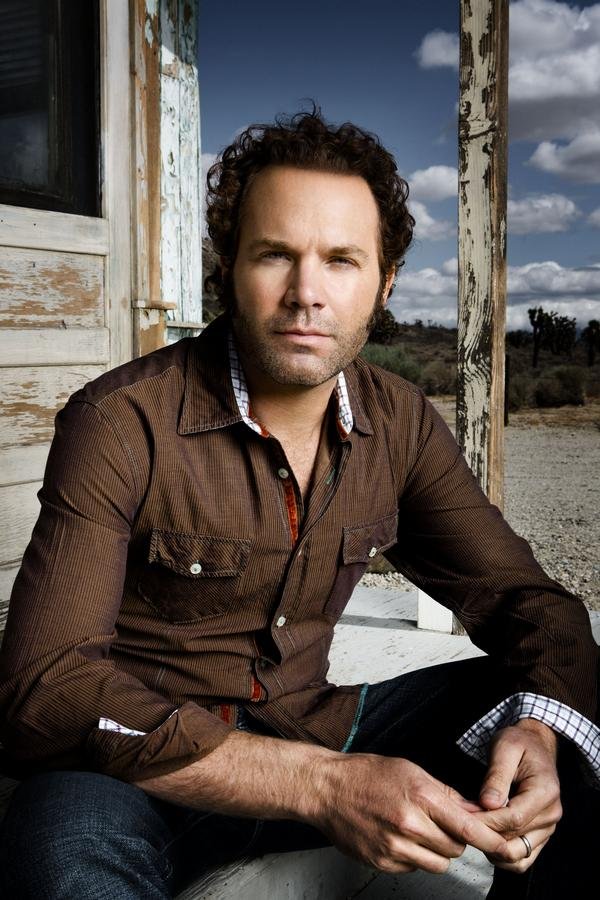

Grammy Award Nominee and platinum-selling artist Five for Fighting (aka John Ondrasik) has kicked off his current tour with the October String Quartet, which includes esteemed Broadway musicians, and will perform over two decades of the band’s hit songs, fan favorites, and recent viral sensations.

Five for Fighting has released six studio albums, including the platinum certified America Town and The Battle for Everything which launched the chart-topping classics “Superman (It’s Not Easy)” and “100 Years.” Both tracks have earned tens of millions of streams, a place in the American Songbook, and placed Five for Fighting as a Top 10 Hot Adult Contemporary artist for the 2000s. Five for Fighting’s music has also been featured in more than 350 films, television shows, and commercials.

Ondrasik’s passion for supporting humanitarian efforts and freedom has been a long-standing commitment for him as well. He’s recently been writing songs about events around the world from a human perspective including “OK (We Are Not OK)” and “Can One Man Save The World?” which was inspired by the courage of President Vladimir Zelenskyy and the people of Ukraine. He performed the song in Ukraine with the Ukrainian Orchestra

amongst the ruins of the Antonov Airport.

The unique nature of the current October String Quartet shows – which includes Katie Kresek (Violin), Melissa Tong (Violin), Chris Cardona (Viola), and Peter Sachon (Cello) – allows Ondrasik to go behind the music, share stories (including about recent overseas trips), and interact with his audiences while also allowing for a deep dive into his catalog.

Al Gomes (Motif): John, in concert you perform completely separate shows with a full rock band, and then with the October String Quartet. It’s very rare for an artist to perform back-to-back tours with a completely different configuration. Talk about your personal and musical transition from one to the other.

John Ondrasik (Five for Fighting): It’s great. It keeps everything fresh. I literally just finished my rock band tour this weekend. And they both are so different. First of all, they’re all incredible musicians. My rock band are players that have been with me for, you know, over a decade. Pete Thorns played with Chris Cornell, Melissa Etheridge – iconic artists. My drummer Randy Cook is an in-demand guy for every arena show. And they’re also my second family. We’ve been friends so long. So it’s so much fun to go out during the summers. We play larger venues. We play outside. We play the rock songs.

And then, during the spring and the fall, we transition to the string quartet again. World class Broadway players. My lead violinist, Katie Kresek, won a Tony Award for Moulin Rouge. So, every night, I get to witness the entire quartet’s magic, and it’s a much more intimate show. It’s a more theater show. It’s a sit-down show. I can pull certain songs from my catalog because I have had such incredible arrangements from amazing string composers throughout my career.

And it’s a more storytelling show, you know. It’s very intimate. And also, halfway through the concert, I walk off and let the quartet kind of show their genius. So, both shows are really exciting and fun. And I think it keeps it fresh for me, as well as doing solo shows and keynotes. So, all those different permutations make everything, again, feel a little bit new. And I’m always excited to reconnect with my friends.

AG: The way that you’ve approached this – I don’t think there’s anybody else out there doing different types of concerts so close to each other. Usually, an artist will take a year off between different configurations. You figured this out to be the ultimate way to keep it fresh.

JO: Yeah. Also, I’m certainly not doing, you know, the 200 shows a year like I used to do. So, this is a really nice kind of way to stay out there – do 50 shows or so a year, and not get completely exhausted. I’m not 24 anymore. The bus rides seem a lot longer, you know? And I have a lot of stuff outside of the kind of performing that I do. So it’s a good healthy thing for me. And also, I think it’s nice for the fans because you can kind of see whatever show you like to see. If you wanna come sit down in the theater, you can do that. If you want to go to Grand Rapids and be outside with 2,000 people and singing along, you can do that. Or you can do both. So yeah – I think for both my audiences and for me and the musicians, it works out well.

AG: I would think that there’s many fans that go to both shows.

JO: Oh, yeah. We have a couple of Grateful Dead type fans who we see at every show, which is fun. We try to mix and match around the country every year. So, we get to all areas of the country at least once every couple of years.

Tim Labonte (Motif): I actually went to go see your string quartet concert here in Rhode Island a few years ago. And I think you nailed it with the storyteller description. When I was sitting there, I kind of felt like I was having my own Five for Fighting Unplugged or Storytellers show.

JO: Yeah. Thanks. I mean, that’s the way I enjoy seeing some of my favorite artists. I’d like to see James Taylor with the guitar and talking about where was he when he wrote his classics. It gives you a more kind of intimate relationship with the audience. At the rock show, if somebody screams out a song from the back row, you never really hear it. But at these shows, people can ask for songs, or we can even have conversations with audience members. And that’s a lot of fun.

AG: “Superman (It’s Not Easy)” and “100 Years” are still resonating with each new generation. Many people have written about why the recordings have such longevity. What’s your personal take on it?

JO: Yeah. I mean, as a songwriter, I think the thing you hope for most is that your songs stand the test of time. And I was joking during this last tour that there are now young people singing “100 Years” in the front row that were not born when I wrote that. You know? There are people of my generation when I wrote “100 years” and “Superman,” and now their kids have kids. And it’s just fun as a songwriter to kind of experience that

trajectory.

But I think first of all, “Superman,” of course, with the connection from 9/11 and being one of the songs that recognized our heroes, that is something that it’s just kind of part of American history. And “100 Years” – I think the nice thing about that song is that we’re all in there somewhere, right? Unless you happen to be 103, and God bless you if you are, we’re all in there and we’re kind of doing the best we can. We find ourselves at different stages of our lives, and that sentiment, I think, is rather timeless. Right? Appreciate the moment. And so, the fact that those two songs – you hear them, and even some others – you hear in the Home Depot or in the dentist chair, and that’s pretty wild for me twenty-some years later.

TL: John, when you’re bringing 10 to 12 songs to the recording studio for a new project, is there a mood in the room or an energy about a particular track where everyone just sort of looks at each other and knows there’s something special going on? Or do things just happen so quickly trying to get a track or a deadline done?

JO: You know, that’s a very good question. I don’t think anyone’s ever asked me that question before. I think it certainly depends, right? These days, very few bands or artists actually record albums that also are together in the room when it happens. As you know, many musicians are scattered across the country, and everybody does their part. When we were recording “Superman,” there wasn’t the band in the room, just my producer Gregg Wattenberg. I think as we started to kind of build that track, we felt that there might be something there that was, you know, different. We had no perception that it might be a hit song. In fact, this was the age of Lilith Fair, boy bands, and grunge music. So we thought it probably wouldn’t be a hit because there was no piano songs on the radio. But we got a sense of something special.

And similar with “100 Years” when we were finishing recording that and listening to it, we felt that, okay – this is a good follow-up to “Superman” in that it’s not “Superman Part Two,” you know. I spent three years trying to write the follow-up to “Superman,” and the tendency of a young artist that has a hit song is to kind of regurgitate the hit song. And so we really

wanted a song that would stand on its own and be the same guy. But we made The Battle for Everything album and didn’t have “100 Years.” So, we knew that we didn’t have the hit. So, I think when we were recording “100 Years,” at the end we’re like, okay, who knows if it’s gonna be a hit, but we think this one could resonate. And it’s crazy. Certain songs – you just know. The record company thought “World” was gonna be a massive song. It wasn’t. “Superman” was an anomaly.

I look at making an album as, okay, you need two songs to try to have enough success where you can make another album. Right? So, you craft the songs in a way that’s palatable for radio. All the things that go into doing that. And Gregg Wattenberg is a master at that. You have nine songs where you can kind of just create and be yourself and maybe go off the deep end. And so, for me, I do lament the death of the album because I think it’s such an important piece of our culture. For the first time in – I don’t know – 10 years – I’m actually considering doing one. The reaction to the latest songs, it’s given me a little more energy to perhaps make another Five for Fighting album.

TL: In the first part of your answer about recording, you kind of sparked a memory. I’m actually a big fan. I’ve been listening to you ever since The Battle for Everything. Didn’t you kind of retreat in a way when you recorded The Battle for Everything? You were recording in a house?

JO: Yes. You know the deep Five for Fighting lore. Yeah, for someone of my generation who grew up in the ‘70s, the dream was to do what The Who and Led Zeppelin and all these bands did and go somewhere – maybe somewhere in nature. And you go with your musicians for like three months and an engineer with a studio, and you just kind of live it. You make the album, you’re recording, everything’s always set up. You’re writing in the morning, and you’re recording at night. And we did have that experience in Mendocino, California with Bill Bottrell – an amazing producer. It was a studio on the side of a cliff. And at night the lighthouse would be going on, and it was Northern California weather. So, it’s kind of cloudy and moody and the ocean’s always smashing on the rocks. And people would always bring us wine because there were 50 wineries within 10 miles of the studio.

And so, it was a wonderful experience. You know, we’ve never really had that again, because those were expensive budgets. But it was magical and fun. And I always look back on it very fondly, which also must have helped bring a different approach to a follow-up album and such.

I mean, in 2001, that was kind of the last big wave for the music industry. I kind of saw that coming. So, I bought a bunch of gear from a studio in Ojai, had my own studio, and we were able to do it that way. And, of course, everybody now kind of does it at home and technology allows you to do it anywhere. But yeah, it’d be fun to do that again one day. And it’s certainly a different process of songwriting than what happens now. But for guys like me, I kind of enjoy that.

TL: That was actually kind of leading into you answering what I was going to ask next. When you broke as a recording artist, you were right on the cusp of this major change, or earthquake rather, of a traditional record market over to this digital instancy.

JO: People forget that Bruce Springsteen broke on his third record. It was very important to give artists the time to mature, to tour, to develop their craft, to hone their performing. And that went away very quickly. And the development of young artists actually shifted from record companies to publishing companies, ‘cause publishers were still doing well since they owned the copyrights. Luckily, I had a very strong publisher who was very supportive of me.

Actually, my wife worked for EMI when I met her, so I had a strong group there. We had to very quickly learn how to make things cheaper. You know, I remember the “Superman” video, cost $450,000, which is “Oh, wow.” The album cost $50,000. Back then they were spending so much money on things like that. And so very quickly, unless you were like a superstar, that all went away.

But I think you just had to be smarter. You had to be more creative. You had to learn how to do things cheaper – be more creative in doing so. Fortunately for me, I was kind of established before that happened. But it’s taken almost 20 years for streaming to catch up. But now the nice thing is that you can hear a song anywhere, and your phone can tell you who it is. And an artist can make music on their laptop for pennies on the dollar. If you’re an artist that knows how to use social media, I think it’s really leveled the playing field. And I think that’s a healthy thing. We just wanna make sure that art doesn’t become a hobby. People need to make living a living at it. And I do think things are getting a little better.

AG: I love hearing your positive attitude about that.

JO: Thanks.

TL: Your music’s been equally universal with its impressive use in films, TV shows, and advertising. Is your approach to writing for film and TV different than to a “traditional” album?

JO: Yeah, of course. Because when you write for film or television, you have a script, you have a tone, you have something to look at. Sometimes, when you’re writing a song, you start with a blank palette. But I always enjoy writing for film ‘cause I have somewhere to start. And then if it works or not, who knows? But if you find the right music with the right imagery, it can be magical. So, I really enjoy it.

I look at it like homework. Here’s my homework project. It’s one thing. I don’t have to write a hundred songs to get 10 for an album. I typically try to find projects that inspire me. And then we write it, we record it, and then I’m done. And it doesn’t take two years. So, I love doing it. It’s a lot of fun. I’ve been fortunate to have some really cool uses and work with some really cool people doing that.

AG: John, you’ve been successful in taking a nonpolitical stance in addressing what many would see as intense political situations, including the conflicts in Ukraine and the Middle East. You’ve made these human issues rather than political ones in how you pull in the public as a human story.

JO: Yeah, you’re right. I take no pleasure in writing these songs. But to me, they are moral messages. Of course, in this day and age, everything’s political. But I do think, at least in my mind, you don’t abandon your allies. America has a tradition of supporting freedom and democracies against totalitarian governments. So many artists have a problem saying that. But I do think the arts is critical in how we get to younger people. Many of them are not getting the other side of, in my mind, the truth. And they don’t read The Wall Street Journal. They don’t watch the news. They don’t listen to politicians. So how do you get to them? How do you give them another side of the story? It’s through the arts. And so many people don’t understand that.

I mean, I wrote a song – “OK (We Are Not OK)” – I put it on Twitter, I made a video, and it’s become kind of a global thing that’s from one little song from a guy. But I think it shows how the arts can affect culture. And the fact that that song has done that, I hope other artists of conscience will consider doing that. I think “OK (We Are Not OK)” – it’s reflected in the silence of the arts. The music business likes to pride itself on being on the front foot of

human rights. Certainly, the songs from the ‘60s and the Civil Rights movement was critical. The Vietnam anti-war songs, Sun City, Band Aid, Live Aid, The Concert for New York City. And that’s reflected in the song “OK (We Are Not OK).” And we’re not.

AG: And you’ve also physically put yourself in harm’s way by going to these conflicts to record and perform too.

JO: Yeah. My wife’s not very happy with that. You know, when I had the opportunity to go to Ukraine and perform with Ukrainian orchestras, certainly it was nerve-racking. And you learn where all the basements are, and it’s scary. But, when I went there, it was a transformative experience for me. And also, I got to leave, you know. I was there for five days. Those people have been living under it for almost two years now. And so, it was an

honor to do it. And then of course, going to Israel too. It was certainly traumatic to be there the night Iran attacked, you know, especially ‘cause my son was with me.

AG: Oh wow, John.

JO: I lament bringing him, but I’m glad he was there. When someone’s shooting ballistic missiles at you, it’s nerve wracking. But it also gives me a sense of the fortitude of people and to see how they kind of withstand that and their attitude. So, I think it’s important for me to do that – to not just talk, but to walk the walk. I look at my role now as shining the light on true heroes and people who really deserve it. Not me. Certainly, the women of Afghanistan who still can’t go to school. Certainly, the Ukrainians who’ve been fighting this Goliath – Zelenskyy and company. And so, I’m happy to use my platform to highlight those people through these events, and that’s what I’ll continue to do.

AG: Are you sharing some of these experiences with your audiences on your current October String Quartet tour, both with stories and visually?

JO: Oh, yeah. So, we actually play “Can One Man Save The World?” with the audio from the Ukrainian orchestra in a video that we took with our phones in Ukraine. And I speak and give a long kind of setup. I play a video of my performance at Hostage Square behind me while I’m singing. And it’s very emotional. We actually had a heckler or somebody get very angry at our last show. And, you know, that kind of what comes with what we’re doing.

But I think part of the problem is that people are so scared to speak out for the right thing. That they’re intimidated by these bullies who scream at you during shows. And that’s why I keep telling my colleagues, every time somebody stands up, it makes all of us safer. It makes all of us stronger. And the last image of my video in Ukraine, the video is Martin Luther King, Jr. saying his famous quote – silence in the face of evil is complicity. And

we’re seeing a lot of freaking complicity. And so, the more people that stand up, it makes everybody safer, and it makes the world safer.

AG: Do you have any surprises you’re planning for your upcoming concerts with the October String Quartet?

JO: We always have a cover or two. We always do a song that recognizes our military families every night. I never know what the quartet’s gonna surprise me with. They always play one a night like Guns N’ Roses.

AG: So, you have some surprises in store.

JO: Oh, always surprises. Sometimes we have special guests. And we’re also putting together a yellow ribbon campaign for our hostages. So, we’ll be talking about that. But yeah, you never know with Five for Fighting. I never know half the time when I show up what’s gonna happen.

Five for Fighting with the October String Quartet performs live on Tuesday,

October 8 at 7:30 PM at the JPT Film + Event Center, 49 Touro Street

in Newport, RI.

Tickets can be purchased at

https://janepickens.com/shows/five-for-fighting-with-strings-live or by calling

(401) 846-5474.