[Because of the length of this review, this is the first of two parts: the first part, Eyeless in Gaza provides an overview of the Wilbury Group production and the second part, Brainless in Gaza, provides some additional detailed historical analysis of the script.]

Part of Wilbury Group’s 2018 Festival of New Work, Heresy, by Providence playwright Lawrence Goodman, moves from disappointing to offensive in the course of two acts and 100 minutes.

Very much not a Jewish take on Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner?, Heresy is closer in spirit to Long Day’s Journey into Night by Eugene O’Neill – if one substitutes Jews for Irish, coffee for alcohol, superstition for opiates and Hamas support for tuberculosis. The unusually self-aware Goodman in the official program quotes an unnamed critic who described his work as “exactly what happens when you expose a complete amateur to too much Harold Pinter” before titling his next production An Evening of Highly Self-Indulgent, Semi-Autobiographical Theater: when reading that before the play it seemed a joke, but it isn’t. O’Neill, however, had the good sense to withhold publication of his self-indulgent, semi-autobiographical play until after he was dead. Heresy, which is colorably pro-Hamas, echoes Pinter’s real-life defense of war criminal Slobodan Milošević.

Set in New York City during (presumably) the summer of 2014, Heresy opens as the Liebowitz family welcomes daughter Hannah (Zoë Thompson) home from her sophomore year at a college that, we learn, is less prestigious than Yale, a fact pointed out by her overbearing mother, Judy (Rena Baskin). Her father, Paul (Barry Press), is a psychotherapist who is obsessed with his elaborate and complicated coffee making machine, which is his defense mechanism for avoiding human interaction. Hannah’s brother, Tim (Jason Roth), is taking an involuntary gap year after graduating late from high school because he had to make up a failed class, and he is spending the time playing video games while pursuing his dream job of being a dance party DJ.

Amazingly, none of the characters seem to have so much as barely met each other before the play begins, despite having all lived together for two decades, as Hannah’s parents discover that they really hate each other and the family unravels into shreds. (I warned you about Long Day’s Journey into Night.) Yet little of the stress tearing apart the family has anything to do with the Arab-Israeli conflict, which ends up as a pseudo-serious theme grafted onto the family drama.

It’s possible to do this well: The Quarrel is a clash of ideas based on My Quarrel with Hersh Rasseyner by classic Yiddish writer Chaim Grade, but Goodman is not Grade.

Hannah has become suddenly politically aware: She tells her parents she is dating a Palestinian boy at school, but we learn almost nothing about him except that his father is a doctor in Gaza and he is going there for the summer to help his father. Hannah eventually says things such as, “Thank God for Hamas,” and attends an anti-Israel protest rally at the United Nations for which she has made signs that read “Zionism = Racism,” “Israel Murders Children,” “Israel Out of Gaza,” “Free Palestine” and “Stop Israeli Aggression Now.” She becomes distraught when she learns from reading in The New York Times on her iPad that Israel is invading Gaza, which catalyzes her decision to travel there herself, which she does and her father agrees to pay for over her mother’s panicked objections. By the end of the play, the character of Hannah deteriorates into a ridiculous parody, literally wearing a Palestinian keffiyeh, the distinctive head scarf that became a political symbol during the 1930s and was most famously the trademark of Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) leader Yasir Arafat.

Hannah’s father Paul is a “culturally Jewish” atheist who vehemently objects when his wife Judy places a mezzuzah (a Jewish religious object) on their doorway, and he attends the anti-Israel rally with Hannah; he later says that he wishes the State of Israel had never come into existence.

Judy recently lost her grandmother, whom she says was her only source of love and warmth growing up because her own mother was incapable. This leads Judy to embrace Jewish practice as a kind of irrational superstition, installing the mezzuzah as an amulet against misfortune and lighting Shabbat candles despite not remembering the one-sentence blessing – although Hannah, inexplicably, does. (Shabbat candles are not an exotic item: you can buy them at Stop and Shop, and the blessing is printed on the box.) Near the end of the play Judy screams at Hannah, saying she takes pleasure in seeing the Palestinian Arabs killed because they deserve it, a morally indefensible position relegated to the extreme lunatic fringe.

Weirdly, the ethical center of the family becomes ne’er-do-well son Tim, who at least has an intolerance for hypocrisy and artifice that renders him the only likable (or tolerable) character. Roth’s brilliant and charismatic portrayal has him purporting to be, in various chameleon-like guises, an African-American hip-hop artist, a convert to the Nation of Islam (a black hate group) and a chasidic Jew. In his best scene, he tests his increasingly uncomfortable but supposedly liberal mother with whether she would accept him if he were gay (of course), if he were dating a black woman (yes), if he were a Republican (well, she says, that’s pretty close to being a Nazi) and – finally – if his career goal was to be a professional DJ (of course not).

Tim accuses his sister Hannah of becoming a terrorist by throwing in with Hamas, a mocking accusation that nevertheless has an element of truth given that the group has a charter with a stated goal of abolishing the State of Israel to take over the land and kill all of its Jews; is officially classified as a terrorist organization by Israel, the United States and the European Union; and is financially propped up by unabashedly anti-American and anti-Western agitators such as the Islamic Republic of Iran. At one point, Goodman almost acknowledges that some of the Palestinian Arabs are not nice when a news report plays on the iPad about a terrorist bombing in a Tel Aviv cafe. Politically, Tim is at heart an anarchist who is unwilling to respect any of the sacred golden calves worshiped by the rest of his immediate family, leaving Tim arguably most in touch with reality.

While the script offers Roth acting opportunities as Tim, and he does an impressive job with them, the script presents a challenge for the actors in the other roles due to their one-dimensional limitations. Thompson is at her best as Hannah when finally admitting to her mother how much of her life has been motivated by yearning for maternal approval, and everything from tone of voice to body language is pitch-perfect. Baskin is likewise at her best as Judy in her succession of depressing epiphanies about how much damage she has done to everyone around her. Press is unconvincing as a psychotherapist, but very convincing as a father and husband who has had way too much coffee. The obvious abilities of the actors illuminate Goodman’s strengths and weaknesses as a playwright: he understands families a lot better than he understands Middle Eastern politics, so his plays would be a lot better off following the path of Eugene O’Neill rather than Harold Pinter.

Ultimately, the utter absence of any principled voice for Israel and Zionism renders the play pointless: All of the conflict turns upon family drama and personal histories, thereby trivializing the Arab-Israeli conflict by turning it into irrelevant window-dressing. Judy, who is apparently intended to be the pro-Israel voice, devolves into a straw-man caricature of what an extreme left-winger would imaginatively concoct of a right-winger, explicitly stating that she relishes the deaths of Palestinians. That’s crazy talk, far outside the political mainstream, taking the play into the realm of the truly offensive by claiming that any sane people think this way.

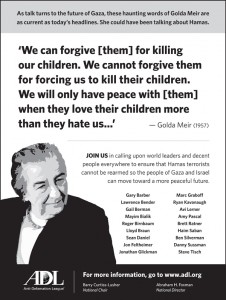

By contrast, during the actual 2014 Gaza conflict, the Anti-Defamation League (ADL) bought full-page advertisements making exactly the opposite statement in The Hollywood Reporter, Variety, The Jewish Journal, The Los Angeles Times, and The Los Angeles Daily News citing the widely repeated (but possibly apocryphal) quote from the late Israeli prime minister Golda Meir about the Arabs: “We can forgive [them] for killing our children. We cannot forgive them for forcing us to kill their children. We will only have peace with [them] when they love their children more than they hate us.”

One of Hannah’s protest signs, “Zionism = Racism,” touches a particular nerve: It echoes the notorious United Nations General Assembly Resolution 3379 – remember, her protest rally is at the UN – that derailed peace negotiations for decades upon its adoption in 1975 until it was repealed in 1991 to make way for the Madrid peace conference that would lead to the 1993 Oslo Accord and the 1994 Israel-Jordan peace treaty. When the original resolution was adopted, US ambassador to the UN Daniel Patrick Moynihan immediately walked to the podium and gave a now-famous speech: “[The United States] does not acknowledge, it will not abide by, it will never acquiesce in this infamous act.… A great evil has been loosed upon the world. The abomination of antisemitism… has been given the appearance of international sanction.” (Moynihan’s whole speech lasted nearly a half-hour.)

At a talkback after the play, I confronted playwright Goodman directly on the main concerns explained above, giving him the opportunity to respond verbatim.

Me: It seems to me that the conflict was not on point. In other words, people are fighting about the family drama and disputes and the history of the family, but the political aspect of the play is not a matter of conflict in any serious way in the family. Everybody is articulating either some very left-of-center position that varies only in degree, except for the brother who is an anarchist and throws bombs into everything. Was that intentional, or did you not want them to start political conflict here?

Goodman: I feel like there is political conflict. I think originally Judy is kind of neutral or ignorant about Israel and then I think she comes into her Judaism and adopts a right-wing position that puts her at odds with Hannah.

Me: Do you think the Israeli right wing would agree with Judy’s speech at the end that she takes pleasure in seeing Palestinians killed?

Goodman: I think so, yes. I think, there was a– Wasn’t there an incident where they were cheering as they watched the bombs, the right wing was cheering as they watched the bombs fall on the Palestinians? I know that I have heard American Jews feel that, I’ve felt, that surge of satisfaction that comes from Jews being strong and standing up for themselves–

Me: But that’s not what she says, though. She’s saying that she takes pleasure in seeing Palestinians killed. I don’t remember the exact line, but you may.

Goodman: Do you think when Americans watch the war in Afghanistan they take pleasure in seeing the Taliban killed or not?

Me: I hope not. I hope the American soldiers who had to do the killing weren’t taking pleasure in it. That’s certainly not part of what soldiers are taught. They’re taught that they have a job to do, and it may be a very unpleasant one, but if people are actually, to paraphrase Arlo Guthrie, shouting ‘Kill, kill, kill!’ they’re not welcome in the military.

Goodman: Okay. And speaking of the military, speaking of what I’ve heard, at least since 9/11 people have been revengeful, often a lot of people, people I knew, often little people, take pleasure in seeing us in an upper hand position. Think hard what it means to – war is, for many people, violence is the reality.

Me: I’m sure there are people who think that way. I would hope it is not the majority and is not policy makers. I don’t think that the decision for the United States to respond to 9/11 in Afghanistan was done out of revenge or pleasure. One would think one could at least make a principled argument for it on rational grounds. No one makes a rational case here in this play.

Also at the talkback, there was a consensus among the audience that the new performance space used by the Wilbury Group, which is cavernous and surrounded by cinderblock, made a substantial part of the dialogue inaudible, particularly in the early part of the play; this has been a serious problem that I have noted previously.

What destroys any chance Heresy has as a dramatic work is that Hannah is a simplistic foil for a debate that never comes because there is no rational case made for the opposite view. At least three of the four characters (Hannah and her parents) are thinly drawn cardboard cutouts based upon Jewish stereotypes, and the remaining one (Tim) is played for comic relief. Hannah is explicitly pro-Hamas, the supposedly moderate view expressed by her father is that he wishes the State of Israel never existed, and the supposedly pro-Israel view expressed by her mother, motivated by a Judaism of irrational superstition, is that she takes pleasure in the killing of Palestinian Arabs. I don’t know any real families like that.

Heresy, by Lawrence Goodman, directed by Dan Gidron, performed by Wilbury Theatre Group, 40 Sonoma Court, PVD. Telephone: (401)400-7100 E-mail: info@thewilburygroup.org Two acts, about 1h40m including intermission. Through Apr 29. Refreshments available, including beer and wine. Web: thewilburygroup.org/festival-619778-939975.html Tickets at the door only.

[Continued in part two, Brainless in Gaza: motifri.com/heresy-brainless-in-gaza]