Playwright Lillian Hellman was an awful person: Self-hating Jew, apologist for Stalin, plagiarist of the lives of other people, possessed of a remarkable talent for alienating friends, and prone to ruinous litigation. Hellman, perhaps because of her own deep character flaws, mastered an uncanny empathy in writing plays about awful people. Being evil is not sufficient to make one a good writer – Italian fascist dictator Benito Mussolini infamously authored a romance novel that Hellman’s friend and colleague Dorothy Parker reviewed in The New Yorker as “absolutely unable to read my way through it” – but it seems to help.

Indeed, it was Parker who suggested the title of this play, inspired by the biblical Song of Songs 2:15, which the King James Version translates, “Take us the foxes, the little foxes, that spoil the vines: for our vines have tender grapes.” Glossed more plainly, this is a biblical warning: Don’t let foxes, especially young foxes who have not yet developed the slyness for which their species is renowned, into the vineyard, because they will indiscriminately eat the immature sweet-smelling grapes along with the mature grapes.

The Little Foxes is a family drama set in the American South of 1900, precisely on the dividing line between centuries old and new, as the play itself notes in dialogue. Disconcertingly autobiographical, the focus is on three siblings: “Regina” (Steph Rodger), “Ben” (Francis Gilleese) and “Oscar” (Michael Petrarca), whose father left an inheritance to only his sons rather than his daughter. Regina has therefore sought financial security by marrying “Horace” (Robert Schmiegel Remigio), a successful but not very ambitious banker, who has developed a heart condition that confines him to a wheelchair. Oscar has married the gentle but innocent “Birdie” (Stephanie Traversa) solely in order to obtain her inherited cotton plantation, driving her to alcoholism. Oscar’s and Birdie’s son “Leo” (Ross Gavlin) is stupid, dishonest and a womanizer, all of which repulses Regina’s and Horace’s 17-year-old daughter “Alexandra” (Katrina Rossi), interfering with Oscar’s scheme to see them married, despite being first cousins, in order to keep the family fortune unified. The family are mesmerized by the opportunity to build a local cotton mill in collaboration with “Mr. Marshall” (Dan Victor) of Chicago, who sees the South as a bastion of low wages and enforced labor peace, but they need to raise the money to do it. Honest and faithful black servants “Addie” (Krystal Hall) and “Cal” (Ezekiel Seun Olukoya) try to support the decency of Horace and Alexandra, but are outmaneuvered by circumstance. Through a series of self-serving and back-stabbing actions in their unremitting quest for the millions of dollars they expect to flow from the cotton mill, the three siblings manage to alienate each other irredeemably, demonstrating that the avarice needed to acquire great wealth is otherwise ruinous.

The play was originally produced in 1939 at the peak of Hellman’s involvement with the Communist Party of the USA (CPUSA), which she claimed was briefly from 1938 to 1940. This is damning, as biographer Alice Kessler-Harris observed in A Difficult Woman: “If Hellman’s dates are accurate, then she joined the CPUSA after the worst of the Moscow purge trials and in full awareness of them. Not only had she been in Moscow while they were going on, but she had returned to a United States where the press fully covered them.” Hellman’s later admission contradicted her 1952 testimony before the House Un-American Activities Committee where she said she attended meetings from 1938 to 1940, but was never technically a party member.

Some of Hellman’s literary output in service of communism is cringeworthy, such as her Academy Award-nominated screenplay for The North Star in 1943, a propaganda film produced at the height of military alliance between the United States and the Soviet Union during World War II. Showing happy workers on collective farms in Ukrainian villages fighting off Nazis who kill children by drawing blood for transfusion into German soldiers, the film was ridiculed more than 40 years later by Robert Conquest in The Harvest of Sorrow, explaining that in fact the policy of the Soviet Union was to starve to death millions of Ukrainians and Kazakhs during the 1930s, saying that viewers in the Soviet Union acclimated to such ridiculous propaganda would have laughed at the film, although Westerners took it seriously.

Probably Hellman’s most egregious deceit was in her 1973 book Pentimento where, most historians now agree, she misappropriated and plagiarized the life story of Muriel Gardner in what Hellman claimed was the true story of a friend she called “Julia,” a wealthy American who earned a medical degree in pre-Nazi Vienna and later became instrumental in the anti-Nazi resistance, dying in London. Hellman’s account became the basis for the 1977 film Julia, nominated for numerous Academy Awards including Best Picture, Best Director, Best Actress, Best Supporting Actor (twice), Best Supporting Actress and Best Screenplay, and it won three. Gardiner, however, survived the war and published her memoir in 1983, provoking investigations and denials from Hellman regarding the undeniable similarities. When accused of lying about this and other matters by former friend Mary McCarthy, Hellman responded with a vindictive and punitive libel lawsuit that dragged on for four years until Hellman’s death. McCarthy’s biographer Frances Kiernan wrote in Seeing Mary Plain, “In a taped interview with Dick Cavett first aired in January 1980, [McCarthy] had proclaimed, ‘[E]very word she [Hellman] writes is a lie, including “and” and “the.”’”

The Little Foxes was Hellman’s first great dramatic success and remains her most widely produced play. It made her reputation and assured her financial comfort for the rest of her life. Much of its popularity, I would argue, results from the realistic portrayal of its characters and keeping the anti-capitalist propaganda to a minimum. It is generally agreed that Hellman, who was Jewish, based the internecine warfare of the dysfunctional family on her own. Biographer Kessler-Harris makes the point explicitly: “Critics correctly identified [The Little Foxes] (which opened in February 1939, at the height of anti-Semitic attacks in Germany) as a thinly disguised portrait of her mother’s family. Hellman avoided describing the rapacious Hubbard family as specifically Jewish, preferring instead to speak to a more general concern about the corrupting effects of money. Yet the family’s effort to profit from the industrializing new South could easily be interpreted as a depiction of the stereotypical money-grasping Jew… At the time, Hellman insisted that the play was meant as satire, a lesson to illuminate the impact of greed on the lives of innocent people and their children. And surely its success is attributable to the way that message struck an America still struggling to get out of the Depression. Only later would she acknowledge its relationship to her own childhood – and even then it was class, not Jewish identity, to which she pointed. She had reacted to her grandmother’s wealth and the abuse of her class position with anger and self-hatred, she wrote in one of her memoirs.”

Because of this problematic history, The Little Foxes has generally escaped a reputation for antisemitism that would have been obvious in the 1930s when it was first put on the stage, and now many decades later the family at its center strikes us as merely nouveau riche Southerners grasping desperately for acceptance among the established aristocracy of the South, with little explanation for why such social acceptance eludes them – until you know that the family is closely modeled on the playwright’s mother’s family who, being Jewish, were similarly socially ostracized. By 1913-1915, the widely publicized trial and lynching of Leo Frank would drive half of the Jewish population of the South to move away in fear.

Taken as a classic of American drama, The Little Foxes stands, once one gets past its overt socialism and covert antisemitism, as a morality tale about the capacity of ambition or perhaps even of money itself to destroy individuals, and this is what the Epic production emphasizes. The trio of siblings is well-acted by Rodger as the ruthless and scheming Regina and Petrarca as the hotheaded and mercenary Oscar with Gilleese as the cool and calculating Ben. Traversa as the sad and alcoholic Birdie is outstanding, especially during a scene where she becomes increasingly drunk and terrifyingly candid. Remigio as the invalid Horace seems a bit too young and healthy to be entirely convincing in the role, but does well commanding the forcefulness of the character, especially during a scene where he reveals how much he knows of what is really going on to his only trustworthy confidant, his servant Addie. Epic has produced a strong rendition of a difficult play in keeping with prior work.

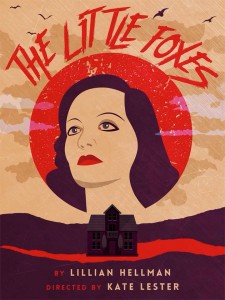

The Little Foxes, written by Lillian Hellman, directed by Kate Lester, performed by Epic Theatre at Theatre 82, 82 Rolfe Sq, Cranston. Through Jan 27. About 2h15m including one intermission. Handicap accessible. Refreshments available. Web: epictheatreri.org Facebook: facebook.com/events/512926545741921 Tickets: red.vendini.com/ticket-software.html?t=tix&e=6b34d1e3fc154cda50218acf02462080