Mixed Magic Theatre takes on a substantial challenge in dramatizing the two most well-known short stories by Zora Neale Hurston, “Sweat” and “The Gilded Six-Bits.” Characterized by subtle word play, idiomatic dialect, puns and heavy-handed biblical allusions, Hurston’s fiction has generally not translated well to the stage. Mixed Magic wisely inserts Hurston as a character, narrating the action and supplying exactly the missing pieces that would be hard to introduce any other way.

Throughout both stories, Jeannie Carson plays Hurston seated at a writing desk and looking very much like every photograph I’ve ever seen of Hurston, complete with fashionable hat. Accomplished local musician Kim Trusty, listed in the program in the role of “Muse,” provides contextual accompaniment, including performing what she told me were original songs written by Ricardo Pitts-Wiley.

In “Sweat,” Delia (Lauri Smalls) is the long-suffering wife of Sykes (Raidge), a cruel man who lives off of her income from hard labor as a washerwoman, carries on with his mistress Bertha (Charmaine Porter), and emotionally tortures her by exploiting her deathly fear of snakes. Delia overhears the townspeople (Jomo Peters, Frederick Douglas Sr, and Carson) like a Greek chorus talking about what a bad man Sykes is but not actually doing anything about it. Eventually a snake plays as central a role as the notional “snake” in the biblical story of Adam and Eve.

In “The Gilded Six-Bits,” newlywed lovebirds Joe (Douglas) and Missie May (Porter) play out a series of deceptions of each other and of themselves, learning that newcomer to the town Otis D. Slemmons (Peters) is not what he seems, but that neither is much else. (A “bit” in this context is derived from the old Spanish “pieces of eight,” where it is one-eighth of a dollar, so two bits is 25 cents, four bits is 50 cents, and so forth; a quarter-dollar coin and a half-dollar coin total six bits.) A white store clerk (Raidge) suggests that race is a factor in blissful acceptance of falsehood.

Mixed Magic employs a strong cast, making the best of somewhat thin material: These short stories were very short. Carson’s narrative as Hurston is especially valuable, because, although much of the original stories is dialogue, about half of the truly memorable lines are spoken by her as narrator. Hurston’s literary strength lay mostly in capturing the lyrical patterns of dialect speech as it reflected her characters. Trusty’s music enormously helps the play, setting pace and tempo that would otherwise approach plodding. Raidge told me that his stage name is taken from his hip-hop performance background and that he is not used to playing a “villain” character as in “Sweat,” but he is remarkably effective on stage despite being a big and powerful-looking man in a role that, for whatever reason, I have always pictured as emasculated and scrawny (although the original story does describe him as a “strapping hulk”). Douglas and Porter are very convincing and true-to-life as the couple in “The Gilded Six-Bits.”

Zora Neale Hurston is today recognized as a seminal influence on African-American literature, but this was not always so. Her reputation as a writer was substantially rehabilitated beginning with an article by Alice Walker in Ms. Magazine in 1975, “In Search of Zora Neale Hurston.” It was not that Hurston was simply forgotten, but that by her death in 1960 she had actively invested 40 years alienating pretty much everyone in the American black community, dissenting on moral and political grounds against everything from New Deal liberalism to the civil rights movement.

Since then, a lot has been written about Hurston, quite a lot of it uninformed, speculative and even ridiculous. Part of the responsibility for that lies with Hurston herself, because deception and artifice are not only a significant theme in her storytelling, but were a major element in her own real life. Walker (admittedly) falsely claimed to be Hurston’s niece so she could buy her a tombstone, and that tombstone asserts a false birth year of 1901 rather than her real birth year of 1891; Hurston’s grave had gone unmarked since her burial because her estate could not afford a marker. Hurston seems to have claimed to be 10 years younger than she was in order to qualify for a scholarship to high school (which was not free then), from which she was graduated at age 27, going on to finish a bachelor’s degree at age 37.

Hurston did not see herself as primarily a writer but as an anthropologist, and it was her studying that subject in the 1920s at Barnard College (the women’s auxiliary of Columbia University) in New York City that brought her into contact with the group of African-American writers in the Harlem Renaissance who with deliberate irony called themselves the “Niggerati,” including Wallace Thurman (who coined the term) and Langston Hughes. Hurston and Hughes became better acquainted when as undergraduate students they ran into each other in Mobile, Alabama, and Hughes, who did not drive, accepted an offer of a ride back to New York City from Hurston, who had a car and a pistol for protection, important factors in the 1920s for blacks traveling in the South. By contrast, Hurston had grown up in Eatonville, Florida, an unusual town that was incorporated in the 1880s specifically as the country’s first self-governing enclave of African-Americans, which she came to see as a kind of segregationist paradise where her father served as mayor and minister of the largest Baptist church.

As an anthropologist, Hurston viewed the use of dialect in her work as a matter of historical truth and accuracy about the South where she had lived, but it gravely offended the New Yorkers who saw in it echoes of white minstrelsy, and this alone would have led to the marginalization of her writing. The most notable example was her non-fiction book Barracoon, a result of several years of interviewing and getting to know one of the last living persons to have been captured in Africa and transported in a slave ship; he arrived in America in 1860, many years after the slave trade was outlawed, a victim of what was even then illegal human trafficking, and Hurston completed her book in 1927 while still an undergraduate at Barnard. No publisher was interested, largely because of her extensive preservation of dialect speech; she quotes the former slave describing the process of the ship captain deciding whom to transport, “De white man lookee and lookee. He lookee hard at de skin and de feet and de legs and in de mouth. Den he choose.” Hurston also seems to have had misgivings about the moral ambiguity of the sale of Africans to the white slavers by the black king of Dahomey, “My own people had butchered and killed, exterminated whole nations and torn families apart, for a profit before the strangers got their chance at a cut.” Barracoon would remain unpublished until this year, 2018, but then would make it onto The New York Times best-seller list; Mixed Magic is holding a community reading of excerpts from the book, free and open to the public, Saturday, Oct 13, noon – 2pm.

Until the success of her first novel Jonah’s Gourd Vine in 1934, Hurston was utterly obscure. “Sweat” was written in 1926 for the Harlem literary magazine Fire!! that lasted only a single issue before it ran out of money and, ironically given its title, its office burned down: the magazine attracted criticism and even outright hatred for addressing themes of domestic abuse, promiscuity, prostitution and homosexuality, as well as for using vernacular dialect; that one-off issue is now famous enough, 92 years later, that you can buy a reprint for about $20. “The Gilded Six-Bits” was written in 1933 and is therefore a much more complicated and multilayered story, but this forces the stage version to simplify it to its essence, stripping away many of those layers.

Hurston’s political conservatism began distancing her from the liberal intelligentsia in Harlem: In the 1930s, she criticized the Depression-era New Deal as a socialist welfare program that would make people dependent upon the government. She eventually was driven to leave New York City and return to the South after a bizarre 1948 criminal trial where she was accused of molesting the young son of her landlord, but despite being found innocent, her reputation was destroyed by the negative publicity. Her literary career in tatters, with her books out of print and producing no income, by the 1950s she was again working as a maid, which was how she decades earlier put herself through undergraduate and graduate school.

Her final break with the broader black community was her opposition to school integration brought about by the Supreme Court ruling in Brown v. Board of Education in 1954, an opposition grounded in her positive personal experience with segregation in her hometown in Florida where the entire local government, including the schools and the police, were under black control. In The Orlando Sentinel she wrote, “If there are not adequate Negro schools in Florida, and there is some residual, some inherent and unchangeable quality in white schools, impossible to duplicate anywhere else, then I am the first to insist that Negro children of Florida be allowed to share this boon. But if there are adequate Negro schools and prepared instructors and instruction, then there is nothing different except the presence of white people. For this reason, I regard the ruling of the U.S. Supreme Court as insulting rather than honoring my race.”

After the article by Walker in 1975, Hurston began to be taken seriously as both an anthropological folklorist and a writer, eventually leading to her enshrinement as part of the foundational literary canon with a 1995 collected works edition from the Library of America. Today, Hurston’s work is a standard part of the curriculum in high schools and colleges. Mixed Magic deserves much credit for bringing the two most well-known short stories by Hurston to the stage with thoughtful adaptations and excellent performances by a strong cast.

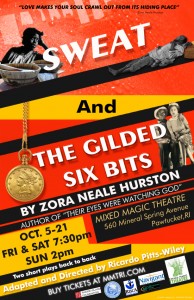

“Sweat” and “The Gilded Six-Bits,” adapted and directed by Ricardo Pitts-Wiley from the short stories of Zora Neale Hurston, at Mixed Magic Theatre, 560 Mineral Spring Ave, Pawtucket. Through Oct 21. Telephone: 401-305-7333 Web: mmtri.com/2018/09/02/back-by-popular-demand-sweat-and-the-gilded-six-bits Tickets: brownpapertickets.com/event/3614555

Community reading of excerpts from Barracoon: The Story of the Last “Black Cargo,” free and open to the public, at Mixed Magic Theatre, 560 Mineral Spring Ave, Pawtucket. Oct 13, noon – 2pm.