RI has detected its first probable case of monkeypox virus. The state Department of Health (RIDOH) said in a statement that a male patient in his thirties who resides in Providence County is hospitalized in good condition after testing positive for an orthopox virus, which is a genus of viruses that includes moneypox. The case is awaiting confirmation specifically for the monkeypox virus from the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

The RI case is believed to be a result of travel to Massachusetts, where according to the CDC one case was previously identified. RIDOH said they are conducting contact tracing to identify individuals who may have been exposed to the RI patient while he was infectious, and contacts will be monitored for three weeks after their last day of exposure.

Interim RIDOH Director James McDonald said in the statement, “While monkeypox is certainly a concern, the risk to Rhode Islanders remains low – even with this finding. Monkeypox is a known – and remains an exceedingly uncommon – disease in the United States. Fortunately, there is a vaccine for monkeypox that can be given before or after exposure to help prevent infection. RIDOH continues to engage in active case finding and we have been communicating the latest information with healthcare providers so that they have the information they need to help us ‘identify, isolate, and inform.’”

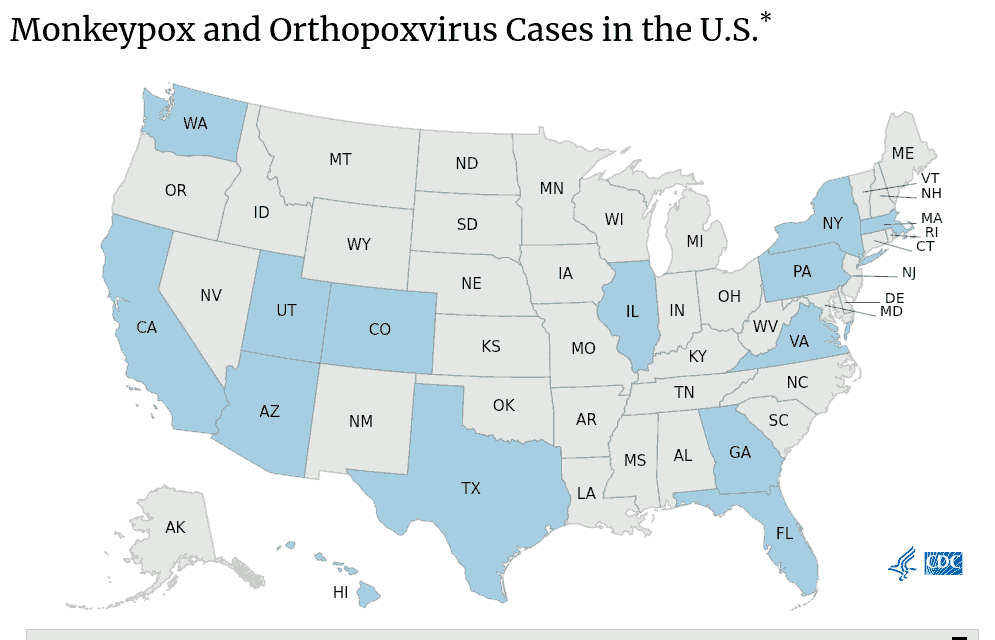

As of yesterday (June 9), the CDC had confirmed only 40 monkeypox cases in the United States. Worldwide there have been 1,200 cases across 29 countries primarily in Western Europe, including the United Kingdom, Spain, Portugal, and Germany, although 100 were in Canada. RIDOH said, “While anyone who has been in close contact with a confirmed or suspected monkeypox case can acquire monkeypox, people who have recently traveled to a country where monkeypox has been reported or men who have sex with other men are currently at a higher risk for monkeypox exposure. It is important to avoid stigmatizing any groups that may be considered at higher risk of exposure to the disease.”

Because the risk of exposure is so low, precautionary vaccination against orthopox viruses is recommended by the CDC only for clinical laboratory workers or researchers handling animals susceptible to infection, but for anyone actually exposed “CDC recommends that the vaccine be given within 4 days from the date of exposure in order to prevent onset of the disease. If given between 4–14 days after the date of exposure, vaccination may reduce the symptoms of disease, but may not prevent the disease.”

Monkeypox and smallpox

Smallpox is another orthopox virus and until its eradication a half-century ago it killed about 30% of those infected. Monkeypox has a case-fatality rate of 3-6%, according to the World Health Organization (WHO), but there are two known variants commonly termed Central African and West African, the former about twice as deadly as the latter. Monkeypox typically causes death or severe injury through complications such as pneumonia, encephalitis, or sepsis, all highly amenable to effective treatment with modern healthcare, and death outside of Africa is extremely rare. Usually monkeypox patients recover on their own within two to four weeks.

It is believed those vaccinated against smallpox before routine vaccination for the general public ended in 1972 likely retain significant protection against monkeypox even decades later; the US military continued routine vaccination against smallpox until 1991. “Past data from Africa suggests that the smallpox vaccine is at least 85% effective in preventing monkeypox,” the CDC said, but also cautioned that “Smallpox vaccination can protect you from smallpox for about 3 to 5 years. After that time, its ability to protect you decreases.”

Monkeypox ways of infection and symptoms

Infection with monkeypox usually occurs either from direct contact with infected animals (blood, bodily fluids, or lesions), especially rodents, or from close contact with infected humans (respiratory secretions, skin lesions, or recently contaminated objects). “Transmission via droplet respiratory particles usually requires prolonged face-to-face contact, which puts health workers, household members and other close contacts of active cases at greater risk,” according to the WHO.

Monkeypox can spread “through contact with body fluids, monkeypox sores, or shared items (such as clothing and bedding) that have been contaminated with fluids or sores of a person with monkeypox. Monkeypox virus can also spread between people through respiratory droplets typically in a close setting, such as the same household or a healthcare setting. Common household disinfectants can kill the monkeypox virus,” RIDOH said. “Monkeypox is not known to spread easily among humans; transmission generally does not occur through casual contact. Human-to-human transmission occurs primarily through direct contact with body fluids, including the rash caused by monkeypox. Transmission might also occur through prolonged, close, face-to-face contact. The time from someone becoming infected to showing symptoms for monkeypox is usually 7−14 days but can range from 5−21 days. Infected people are not contagious before they show symptoms.”

“Symptoms of monkeypox include fever, headache, muscle aches, exhaustion, and swollen lymph nodes. Infected people develop a rash, often beginning on the face then spreading to other parts of the body, that turns into fluid-filled bumps (pox). These pox lesions eventually dry up, scab over, and fall off. The illness typically lasts 2−4 weeks. Currently, there is no proven, safe treatment for monkeypox, though the limited evidence available indicates that smallpox treatments may be useful. Most people recover with no treatment,” RIDOH said. “Anyone who has symptoms of monkeypox should call their healthcare provider before going to the office for an appointment. Let them know you are concerned about possible monkeypox infection so they can take precautions to ensure that others are not exposed.”