Before the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus shuts down forever after nearly a century, their second-to-last shows will be at the Dunkin Donuts Center in Providence, May 4-7.

Facing persistent severe criticism from animal welfare campaigners, the circus announced in 2015 that it would retire its use of elephants, long the definitive trademark of the self-proclaimed “Greatest Show on Earth.” The total cessation of operations was announced by Feld Entertainment, who have owned the circus since 1967, in a statement in January: “The decision to end the circus tours was made as a result of high costs coupled with a decline in ticket sales, making the circus an unsustainable business for the company. Following the transition of the elephants off the circus, the company saw a decline in ticket sales greater than could have been anticipated.”

In a statement applauding the closure, Wayne Pacelle, president and CEO of the Humane Society of the United States, said, “Ringling Bros. has changed a great deal over a century and a half, but not fast enough… It’s just not acceptable any longer to cart wild animals from city to city and have them perform silly yet coercive stunts. I know this is bittersweet for the Feld family, but I applaud their decision to move away from an institution grounded on inherently inhumane wild animal acts.” He further said, “Ringling’s action is a signal to every other animal-based circus that their business model must change… Kids and other members of the public know too much about the backstory of misery, toil and coercive training to keep patronizing these businesses.”

In 2016, Rhode Island was the first state to legislate a ban on the use of bullhooks, which the Humane Society described as “used to hit and punish elephants in order to control them. Resembling a fireplace poker, bullhooks cause trauma and injury to elephants.”

Attendance has been falling for a decade, and the operators blame a combination of factors, including the declining attention spans of children. According to the AP, Juliette Feld, COO at Feld Entertainment, said, “We know now that one of the major reasons people came to Ringling Bros. was getting to see elephants… We stand by that decision. We know it was the right decision. This was what audiences wanted to see and it definitely played a major role.”

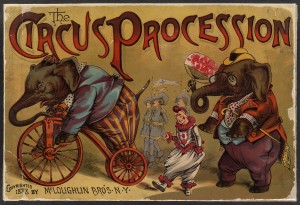

Elephants have a long history with this circus.

Sometime between 1796 and 1805, Hachaliah Bailey bought an elephant, quite likely the first elephant in North America, and named her Old Bet. He found that he could make money by walking her from town to town under cover of night and keeping her hidden in a tent, charging 25 cents admission to see the wondrously strange creature. He was so successful that he provoked the anger of religious fanatics who disliked the competition with church-going on Sunday, and because of what is believed to be such motives one of them shot the elephant to death in rural Maine in 1816.

Undeterred, Bailey got a second elephant, named her Little Bet, and toured with her for a number of years until, on May 25, 1826, she was shot to death in Chepachet, Rhode Island, probably for similar reasons. Exactly 150 years afterward to the day, on May 25, 1976, a commemorative plaque was placed on the Putnam Pike bridge over the Chepachet River.

Some years later, Hachaliah Bailey’s nephew Frederic Harrison Bailey hired a teenaged orphan, James Anthony McGinnis, who eventually became Frederic’s adopted son and took the Bailey surname. By the 1860s, James Bailey and his business partner James E. Cooper were running one of the main circuses in the country and their trademark attraction was, of course, elephants. Competing to buy the first baby elephant born in the United States, they ran into Dan Castello and William Cameron Coup who had started their own circus in 1875 by licensing the name of P.T. Barnum.

By 1882 the two groups merged into the Barnum & Bailey Circus, whose star was an elephant named Jumbo claimed to be the largest in the world. (The English word “jumbo” comes from the elephant, not the other way around.) Even after Jumbo was killed in 1885 by a railroad accident, he was so famous that the hide was stuffed by taxidermists and continued touring.

Eventually the Ringling Brothers, who had started a circus in 1884, bought out their competitor in 1907 and merged it into a single show in 1919. Feld’s claim that the current circus is 146 years old is, in the tradition of predecessor P.T. Barnum, highly dubious.

Disasters have cursed this circus.

In Hartford in 1944, the circus tent caught fire, trapping about 7,000 people, of whom at least 167 were killed and at least 700 were injured. The number killed was disputed, a guess made from reassembling charred body parts. Contributing to the carnage, the tent had been waterproofed using paraffin wax dissolved in gasoline, making it highly flammable. Several circus executives served jail terms and the circus had to pay large damages. The circus abandoned tents in favor of fixed indoor venues in 1956.

In Providence in 2014, an equipment failure during a “human chandelier” act resulted in severe injuries to nine circus performers, eight of whom crashed more than 15 feet to the ground, to the horror of an audience of thousands including small children. The ninth was on the ground under the other performers. The Boston Globe, explaining that seven of the performers were suing Feld Entertainment, reported, “Two patients suffered severe spinal cord injuries, five had open fractures, and one had a lacerated liver.”

After investigating the Providence disaster, the federal Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) determined that Feld had violated manufacturer instructions for a carabiner clip, improperly overloading it and thereby directly causing it to break, and OSHA assessed the maximum fine allowed by law. “This catastrophic failure by Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus clearly demonstrates that the circus industry needs a systematic design approach for the structures used in performances – approaches that are developed, evaluated and inspected by professional engineers,” said Dr. David Michaels, assistant secretary of labor for occupational safety and health, in an OSHA statement. Feld dropped their contest of the citation and fine, settling with the government by agreeing to pay the fine and instituting a safety program to prevent future catastrophes.

Feld Entertainment did not respond to inquires and invitations to comment in the course of reporting this story.