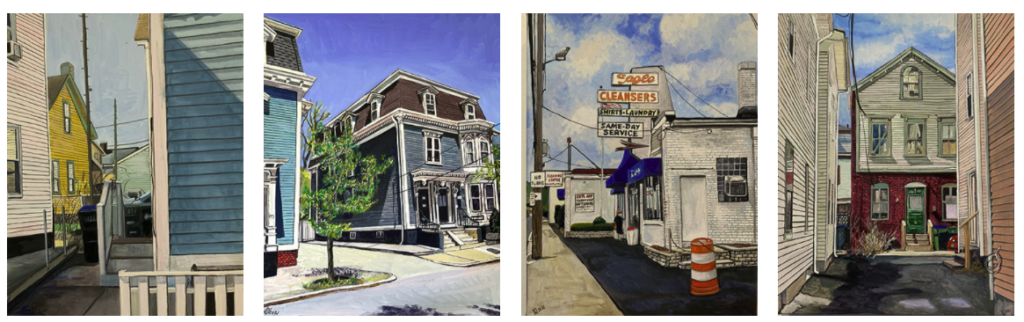

In Umberto Crenca’s newest collection, Divine Providence, it is difficult to tell where the artist leaves off and the city begins. These paintings have been a labor of love – his tribute to the streets he has always called home.

Crenca grew up on Chalkstone Avenue, the son of immigrants who worked in factories all their lives. Home life was hard, and he grew up fast. Art was an early outlet for his frenetic energy, but a talent for provoking anger and pissing off authority sent Crenca reeling through adolescence and straight into rehab. One day, an outreach worker asked him, ”What other interests do you have besides being a wise guy? Because you’re really not good at that.” This was Crenca’s unceremonious boot back into art, but it was not until sculptor Gail Whitsitt-Lynch introduced him to the rampant creativity at RISD that his eyes were opened for the first time to the endless possibilities in art. “It was a world that I didn’t even know existed,” he said.

Bringing that world to lower income communities where opportunities just didn’t exist was the whole idea behind AS220, the non-profit arts organization co-founded by Crenca. He’s since retired from AS220, allowing him time to amp up the pace of his own work. His home base is now in a building that was formerly an Italian American club. He and his wife, artist and musician Susan Clausen, converted the 4,000 square feet into a hive of studios, performance space and galleries. The walls are covered with paintings and sculptures, by Crenca, Clausen and artists from all over the world. It is a hidden cache of treasures hiding under the blue collar grime of a downtrodden neighborhood – an apt metaphor for Crenca’s own life.

Crenco deliberately chose not make his style the most prevalent thing in his new collection. “I’m telling a story here, one I have intimate knowledge of. I know these neighborhoods, so there’s a certain feeling I’m trying to capture, both in the way I compose the pieces, and how I execute them in technical terms that is consistent throughout. They’re not finished until they arrive at that place.” Photographing his subjects first allows him a certain privilege in terms of detail and deep space. “I can manipulate differently than if I was doing plein air paintings.”

The series began at the start of the pandemic; since then Crenca has turned out 119 paintings. “With this series, I think I’m evolving. Now it’s almost undetectable, but 2 years from now, if you look at one of my paintings and compare it to the first one, I think it will be more apparent. When I first started doing art, every time I did something it was different. There was no consistency. But whenever I was exposed to something in an art history book, I realized I needed consistency in my style or I’d never get recognized.” Over the years, the number of paintings in each series has increased. Today, his intent is nothing short of epic: “Imagine if I do 1,000 of these. What kind of exhibit would that be? I only have 881 pieces left to finish. That seems doable.”

For Crenca, struggle is inherent in art: “When we make something, we have this feeling about what we want to achieve, but there’s no way we can possibly explain it, so really, we’re trying to achieve the impossible.” But that has never stopped him from trying. “The most powerful idea is creation. To me, that’s what we’re all wrestling with, this mystery. That’s what artists are trying to express in their totally clumsy way.”

Crenca has traveled a vast distance since Chalkstone Avenue. He’s been given two honorary doctorate degrees, one from Brown, and was one of 10 people honored at the White House, speaking on a panel to representatives from every state. “I hope there’s some value in the way I’ve lived my life, particularly in the last 40 years, that helps other people to feel free to self realize and self actualize … to follow things they feel and are passionate about.” He has always lived life aggressively. “I don’t know any other way, that’s how I approach my art, the way I live, the way I exercise, the way I do everything.”

AS220 was Crenca’s gift to the community. It’s still running with new staff and new people, and Crenca says he believes that’s the way it should be. His ongoing concern is what he is giving back now. “If I can give a story, a long, detailed story of a place, it is helping to validate people’s experience. They can see those things a little differently and have a different feeling about the place. They become part of the series. People can’t go far now. Can this make them feel better about where they are?”

One last thought on creativity: “It’s all within the person themselves, they’ve always had it, they always will have it. But it’s a struggle, how to exercise that freedom.” For Crenca, that struggle is everything.

See the art, buy the book at umbertocrenca.com.