“Grief turns out to be a place none of us know until we reach it.”

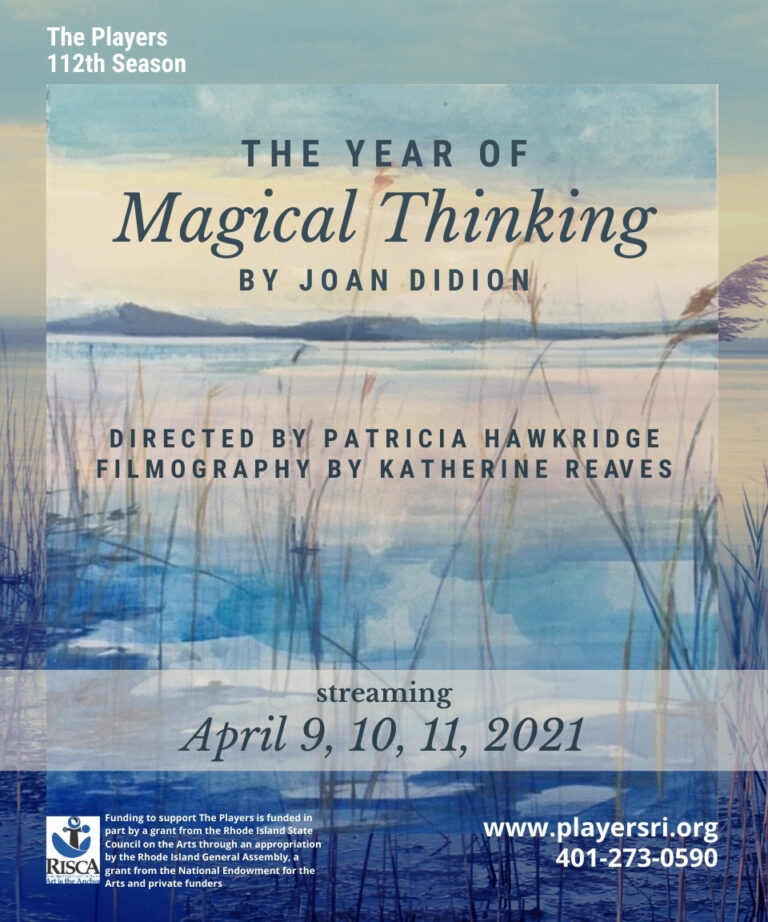

Through April 11, The Players at Barker Playhouse treated audiences to an emotionally intense and creatively directed streaming version of The Year of Magical Thinking, and the result was breathtaking.

In 2005, Joan Didion’s The Year of Magical Thinking was published to near universal acclaim. The book recounted the fairly recent tragedies of Didion losing her husband, fellow author John Gregory Dunne, and the subsequent illness of her daughter Quintana, who passed away shortly before the release of her mother’s masterful meditation on grieving and mortality. It almost immediately became a must-read and went on to win the National Book Award and was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize.

Two years later, Didion adapted the book for the stage, where it played on Broadway and in London. The play was directed by David Hare, and starred Vanessa Redgrave, before she herself experienced the loss of her daughter several years later. Didion included Quintana’s death in the play, which makes it even more heartbreaking than the book. Reading it, it was always clear that, when adapted, it would be done as a solo performance.

The question was: Who would see it?

One-person shows always bring an air of intensity to them, but when the subject matter is this gripping, it seems natural to wonder who would want to sit with these themes while taking in an evening at the theater.

That might be why the switch to digital is a blessing in disguise for titles like this one, that seem to be somewhat more absorbable when you’re able to view them from the security of your home. Seeing the show in New York, I felt immensely exposed being asked to consider such profundity while surrounded by strangers. Though that’s part of the power of theater, it’s interesting how I was able to process the play this time around, and how open I was to its examinations.

First off, there is a story. Didion doesn’t rely merely on reflection to drive the piece. She lays out the events of her husband’s passing and the cruel brevity with which she had to pivot from widow in mourning to mother in action. Redgrave weaved in and out of the play’s two worlds — the contemplative and the narrative — effortlessly, but I remember being concerned that future productions would have a hard time finding an actress who could carry the weight of all that agony.

In Patricia Hawkridge’s digital production for The Players, the evening is not presented as a one-woman show, nor is Didion’s portrayed by multiple women, but rather, we’re given a woman and a chorus, which I think is a very intelligent way to handle the allocation of such heady material, especially if you have such a talented group of women to shoulder the play’s remorse.

As The Woman, I found Carol Schlink to be powerfully understated. The worst thing you can do in a play that could be labeled “sad” is double down on the sadness. Schlink, under Hawkridge’s direction, holds back where she could go over the top and lets out her frustration and denial in bursts that create a portrayal of someone barely held together, but fighting to stay active. It’s that same fight that great actors know how to wage. Play the action, not the feeling — and Schink buoys the part so that her performance comes across as something of a video diary. A confessional. Not something filmed that’s trying to replicate what you’d see onstage, but something more immediate.

The filming component of the piece is excellent — a trait we’re now expecting every time we see a production from the Players. I commend them for continuing to invest in the more cinematic opportunities of their shows. Katherine Reaves is cognizant of the soft touch the story calls for, and her work is exceptional. The original music by Chris Korangy was equally lovely. Praise should also be given to Hawkridge’s assistant director Morgan Salpietro and her production manager Rachel Nadeau. Theater is always communal, but these virtual undertakings call for even more of that company spirit.

In that spirit, the women who make up The Chorus are each outstanding and pull off just the right mix of delicacy and gravitas. I was really struck by the performances of both Paula Faber and Marcia A. Layden, but each of the women did impressive work. Hats off to Kathleen Moore Ambrosini, Eva-Maria Coffey, Kristen Ann Gunning, Michelle Savoie and Janette Talento-Ley.

While I’m sure nobody is eager to produce anything digitally once we’re back to in-person theater, I hope we explore why we typically fear bringing plays like The Year of Magical Thinking to life. If it’s because of how difficult it is to sell it or to make it work onstage, perhaps it’s worth hanging onto those Zoom subscriptions a little longer. The questions Didion poses are essential to the current moment, as so many of us are in the throes of our own experiences with loss and suffering. While that might not make for a fanciful night on the town, it doesn’t make the work any less urgent. Not every story works every time on every stage, but every story deserves a chance to be told. Bravo to the Players for being brave enough to tell this one.