THREE BODY PROBLEM1

“…My resolution is fixed. I shall be free.”

…at that moment he was free, at least in spirit. The future gleamed brightly before him, and his fetters lay broken at his feet.

– The Heroic Slave (1852)

“As to the moral and social influences of pictures, it would hardly be extravagant to say of it, what Moore has said of that of ballads, give me the making of a nations [sic] ballads, and I care not who has the making of its Laws. The pictures and the ballads are alike, if not equally social forces— the one reaching and swaying the heart by the eye, and the other by the ear.”

– Pictures and Progress (1861)

“Can’t no piece of paper put me in slavery/enslave me, so can’t no piece of paper free me.” They turned, slowly to see him. It was as if he appeared out of nowhere and had descended upon them. His hair moved as if there were a wind that was not there, as if he brought with him his own gravity, making all who were present question the very nature of freedom, and, thus, abolitionism. They looked around at each and said to one another:

“Is that what we’re trying to do, to give them freedom?”

“No. We’re striving to support their cause.”

“We want to support your efforts in getting free.”

“In being free.” “In securing your freedom.”

“In ending this immoral institution of slavery.”

“A blight upon mankind.”

“The most righteous cause for my entire lifetime.”

“To end the unjust restriction.”

“Against one’s free will.”

“Autonomy.”

“Agency.”

“God’s will.”

“And love.”

“And justice.”

“A divine calling.”

“Yes, a divine call.”

“We’re instruments of His will.”

“The resetting of divine command.”

“And manifest destiny.”

“Yes.” “Yes.”

“Yes! That is what it is and what we are doing. Yes.”

It swelled, the enthusiasm, and threatened the structural integrity of the room. Could such a space contain all of it? All of the enthusiasm — the gravitational force of true belief?2 Could such a space hold both of these at the same time without being torn asunder or thrown into an unpredictable chaos?

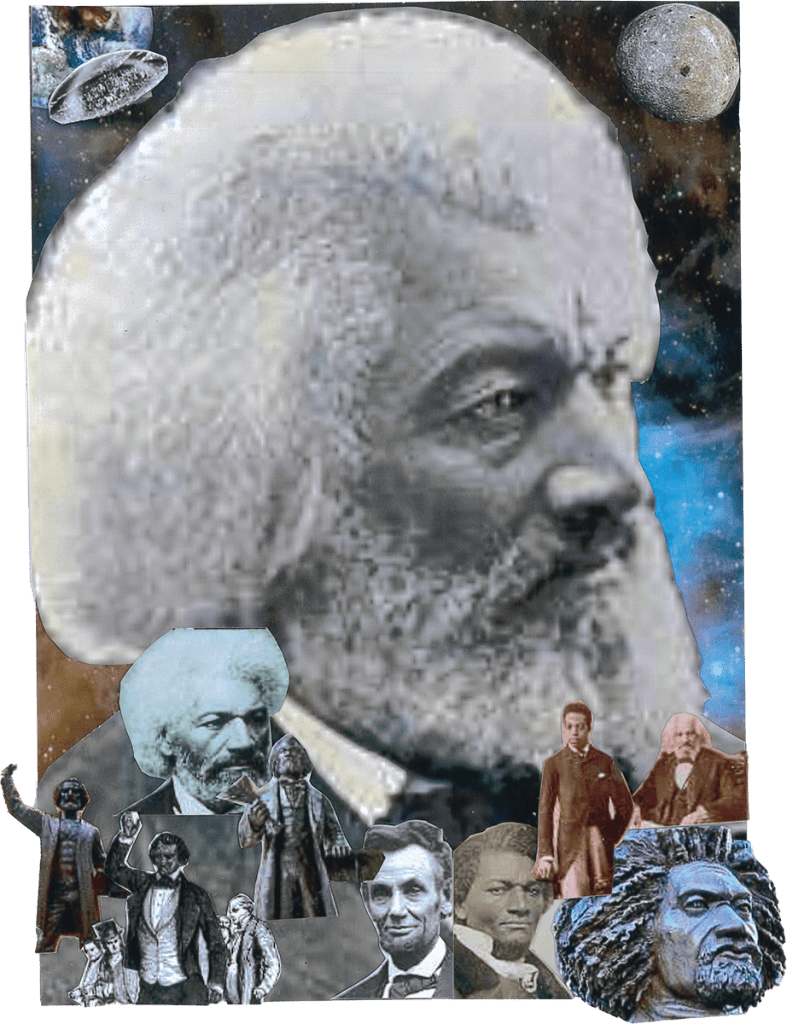

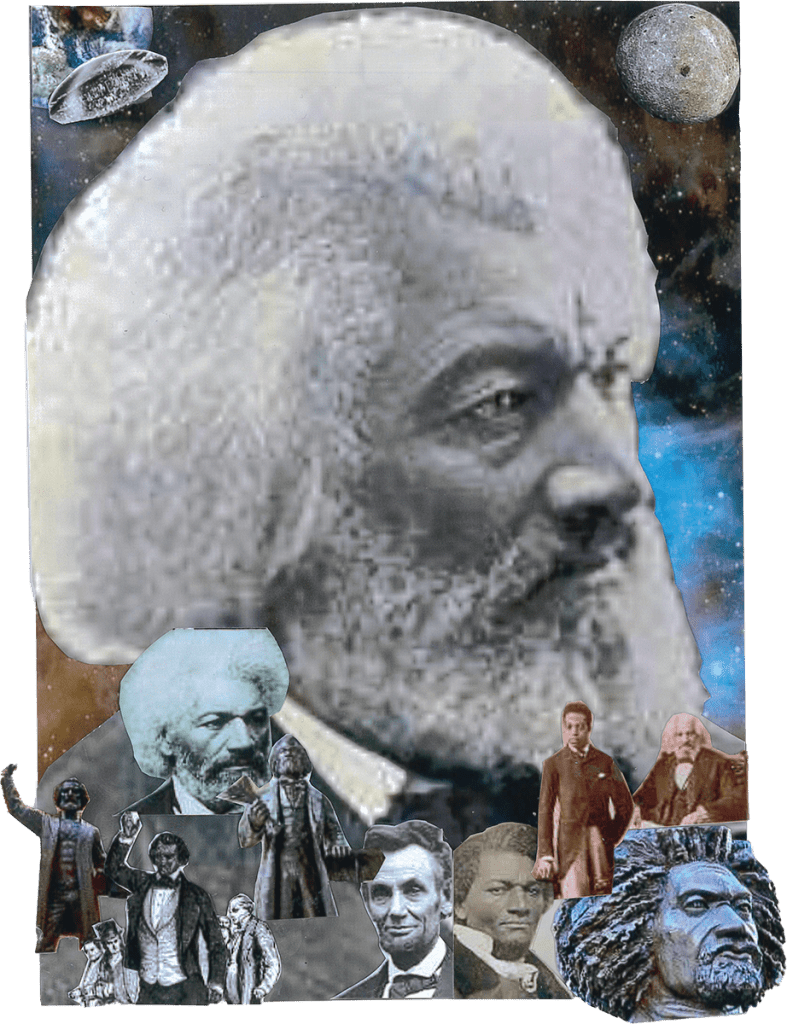

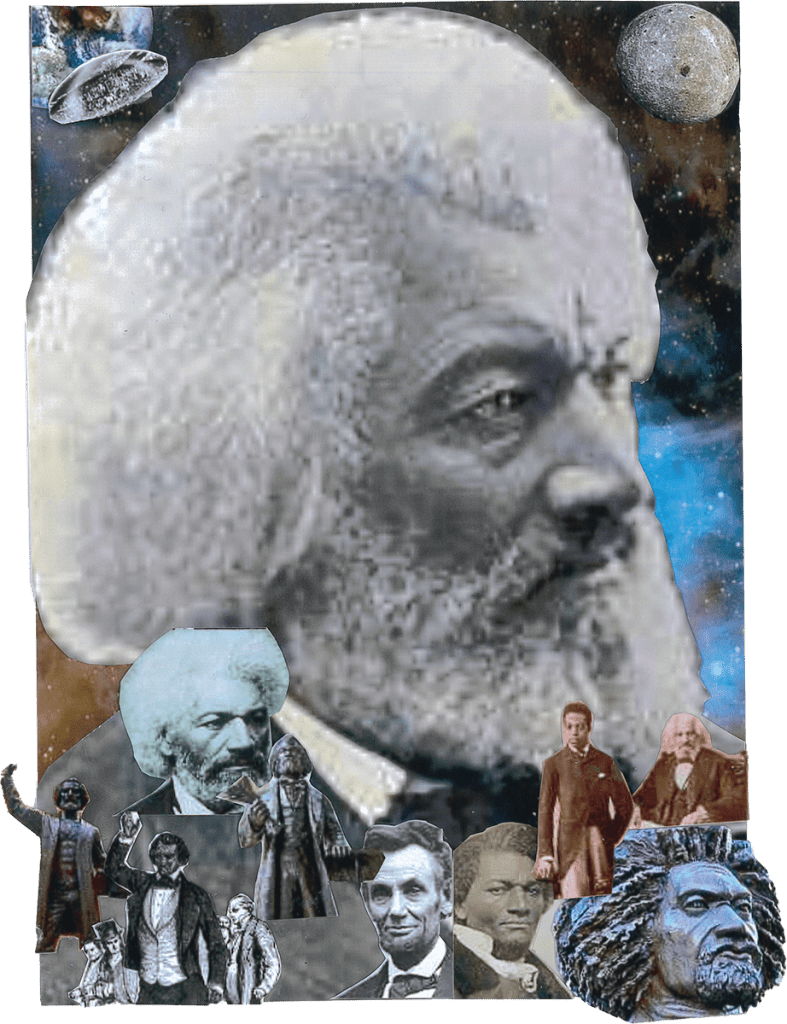

Douglass, he was his own body, large enough to produce its own gravity and too big to be pulled into their gravitational orbit. This was a third body problem. Yes. A third body problem, indeed.

What is freedom? And, what is the meaning of Black freedom?

What is to be done? Whose world is this to be — in which this idea of liberty and freedom persists — around which and through which to consider and reconsider, and think and live this idea? What is freedom and what is its constitutional order in relation to abolition?

“Can’t no paper enslave me, so can’t no paper free me,” he said again cutting across and through the gravity in the room, pulling back against their order and inviting chaos — no cacophony — as the only enduring principle. He then spoke to himself and another, invisible presence in the room:

“Yes. Concurrence.”

“And chaos.”

“And entropy.”

“You can’t know, really know where any body will be at any one time; you cannot predict its motion or movement.”

“Mathematics has officially defined chaos, and this is it.”

“Yes. Chaos.”

The room swelled again, pulling freedom away from abolitionism and towards this, his other gravitational pole.3 And he and they (the abolitionist) began a conversation:

“Like?”

“Like gravity.”

“Freedom is something like gravity?”

“Not gravity, only its consequence.”

“So, freedom is something like consequences?”

“Not like consequences. The consequence.”

“Of what? Abolitionism?”

“No.”

“Of justice?”

“No.”

“Divine provenance?”

“No.”

“Then what? What is freedom like — a consequence of… what?”

“Chaos.”4

“Freedom is chaos?”

Silence.

“Is freedom chaos?”

“No.”

“Then what?”

Silence again.

“Then, the chaos of freedom?”

“Not that, either.”

“Then what is it… the consequence of this gravity which pulls back and forth between us?”

Silence once more.

“What is it?”

“It’s quite simple,” Douglass said, sounding like he was smiling but with a stern countenance his mouth barely moved. His hair stopped moving, for just a moment, the wind surrounding him seemed to pause. And without opening his lips, he finally said, “Chaos is freedom.”

This is the third body problem.

- What is this imaginary we call freedom? ↩︎

- How else could you explain the exuberance in the moment — of the power of argumentation, of reason, of logic? Here, these men, abolitionist one and all, believed, really believed, needed to believe that slavery was a moral failing, but more than that, a failing of reason itself, of the moral structure of sentiment as adjudicated within and through the very notion of the enlightenment: the notion of light as the power of truth. So, they argued, through moral suasion of the necessity of the slavery’s end. And here is where we also find Frederick Douglass—the audience cannot believe that this man, erudite and eloquent is still also a slave whose origin of language and logic befuddles the imagination of true belief. They believed, needed to believe, that he believed as they did, that with the acquisition of their language, he also acquired their beliefs, and, thus, their logic and their morality. Did he? Did Douglass believe that slavery was a logical, rational, and thus moral failing? Or did Douglass distinguish between the rational, the ethical, and the logical and freedom? Could it be that there is another way to think about freedom? To enact freedom in the world, into the world, as the world’s foundation? Can there be a different gravitational force around which this idea orbits — something of a different large body occupying the center of Douglass’ universe? But what is to be done when these two massive objects — one that holds moral suasion of the logic of freedom; and one that rejects moral suasion — come into each other’s orbit? What happens when these two bodies collide over one central idea? ↩︎

- Three objects of a similar mass trying to maintain a stable orbit. In whose orbit shall black freedom be? Douglass, the towering figure, back in 1852 pointed out this three body problem—what will happen in our world, in our nation if black people become or are free — or, better, realize that they have always been free even when not emancipated? What will happen to freedom? What will happen to blackness? What will happen to our world, our nation? What will happen if we change one variable where the idea of freedom cannot be given or taken away or taken back, but is restored as that which has been and is always already there? What sort of chaos will ensue if the idea of freedom is now forced to inhabit and orbit another gravitational pole of an equal mass as that of white supremacy (and its aftermath and wake of white beneficence)? What if Black freedom exists side-by-side with white emancipation? ↩︎

- If freedom is not something that what can be given, and thus cannot be taken away and yet we are in the wake of its erasure, how do we make sense of our living conditions? Is it just a contradiction which requires a new calculus to understand this new mathematics that seems to be in conflict with our living logic? A kind of thinking which can contend with — that is, predict — the coming absurdity, or the failure inherent in its (our logics) very beginning? A perturbation theory? Black freedom is the perturbation theory of Black existence. So, if we can’t predict the exchange between Black freedom and the nation itself, if what it leaves us with is entropy and real chaos, then what? Our great lion reminds us that legislation won’t fix the problem. But more: legislation won’t—or can’t—even help us name the problem when he instructs and I quote again, “give me the making of a nations ballads, and I care not who has the making of its Laws.” (1861) Then what? What’s left? What is going to sway “the heart by the eye” and “by the ear” to get us to see and hear and understand the nature of chaos and the chaos that has descended upon us as our freedom? This is the three-body problem of racialization. ↩︎