“Liberty, equality, fraternity, or death; — the last, much the easiest to bestow, O Guillotine!”

It certainly sounds like a text you can build an exciting evening of theater on, doesn’t it?

Written in 1859 by Charles Dickens, A Tale of Two Cities is considered to be one of the most popular novels of all time. It’s a sprawling epic that covers a wide cast of characters, decades worth of plot, the French Revolution, the Reign of Terror, love, liberty and a paper cutter.

But we’ll get to that in a second.

It has become customary in the month of January for theaters in the area to bust out the classics, and most of the time, that means: “Here comes some Shakespeare.” The definition of a classic can be debated, but primarily it means finding a work from the public domain that you can bring high school seniors to, and if you decide that you want a year off from the Bard, then Dickens might seem like a logical place to go. He’s got great, inherently theatrical characters, blockbuster plots and lots of title value. On press night of A Tale of Two Cities you could almost feel the audience mouth the opening lines along with the actors –

“It was the best of times, it was the worst of times.”

But as you’re saying those words, you also feel a deep-seated apprehension set in, because we know what we’re about to experience. That winding road of Page-to-Stage theater has claimed many a victim, and if you lean into it by highlighting the literary source of your production, you’re really playing with a sharp blade. That’s not to say you can’t find success in the approach, and there are a few successful elements of this production, but sadly, it’s not enough to make it the event it desperately wants to be.

Performed in Trinity’s upstairs Chace theater, you’re immediately struck as you enter by the beautiful two-story set designed by Eugene Lee. Crafted to look like Providence’s Athenaeum, I found myself thinking that if ever my 19 years of working in a library would come in handy when reviewing a play, this was it. Then I wondered –

Why would you set this in a library?

In a note found in the program, artistic director Curt Columbus writes: “…Revolutions always have books as objects that take on greater significance after they occur; whether they underpin the founding of a new nation, or they fuel the literal fires of ignorance, they are always there.”

Okay, I thought, that works for me.

But then the production began, and it seemed as though this play wanted to be anywhere other than within the world of its own concept. It starts with music by Joel Thibodeau, later joined by Christopher Sadlers, which is haunting and lovely, but seems out of place in its setting. It’s not that you’re never going to hear live music in a library, and forgive me if I seem like I’m being too literal here, because a setting can always serve as a simple jumping off point, but throughout the performance, you’re given element after element and none of it seems to be working together.

What is working well is the cast.

Trinity has put together a fine ensemble of actors, and they’re giving it everything they’ve got. As Madame Defarge, Rachael Warren does a fine job making the most of what could be a one-note Dickens villain. Luckily, all of these characters have the turmoil of history driving their objectives, and Warren’s character is right up there with Javert when it comes to being guided by a thirst for vengeance.

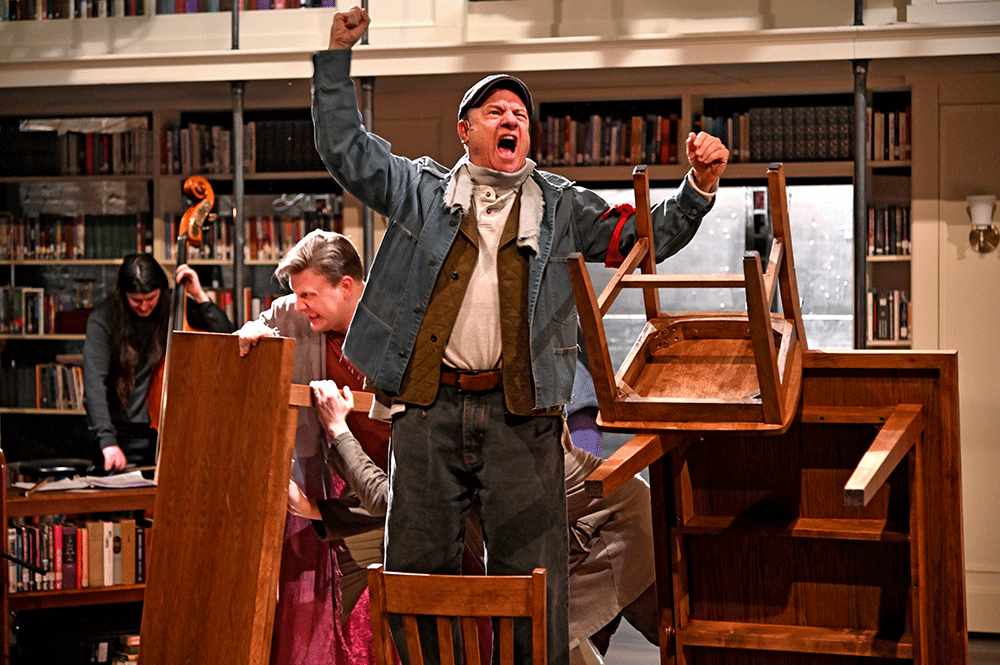

Warren is one of many highly skilled actors who I hoped would have more to do, but who managed to shine with the light they were given. Rudy Cabrera digs into all his characters with a welcome ferocity and some much-needed adrenaline. Timothy Crowe, Jackie Davis, Stephen Berenson, Dave Rabinow and Jotae Fraser all have the versatility required to hold up a play of this size, but unfortunately they only get to show it in fits and starts. Davis’ final character toward the end of the play was so fully realized in such a small amount of time that I wanted to go back and give her more time with some of her other characters. It left me wondering how I was seeking more of a play that had already felt so overlong.

The production is anchored by Taavon Gamble as Charles Darnay and Daniel Duque-Estrada as Sydney Carton. Whenever the two of them are onstage together, we start to feel like we’re actually watching a play and not a-play-based-on-something-better, but unfortunately, those moments are few and far between. Both actors have the magnetism to hold the center of this production, but often, their characters are cast to the sidelines for long stretches of time while we deal with a Dickensian subplot — and boy did he love his subplots.

The woman between Darnay and Duque-Estrada is Lucie Manette, played eloquently by Rebecca Gibel. Dickens gives some of the other female characters in his story much more to work with, but Gibel manages to impart a great deal of dignity in Lucie, and her scenes with Brian McEleney, who plays Dr. Manette, are very moving. McEleney does double duty here in this production as an actor and the adapter of the novel. He does so well in the role, you wish he’d give himself more to do, but so much of the play is hindered by the trappings of the novel that you find yourself in the peculiar position of hoping they’d take more liberties with the source material.

Adapting a novel this expansive is no easy task, and even when done perfectly, inserting narration into a piece of theater can be tiresome, but here it’s done entirely too much. Characters seem to narrate nearly every entrance and exit, thoughts, feelings and major moments that seem like they should have been ripe for theatricalizing instead of speaking out loud. The result is that major events seem to get a passing glance while smaller moments are given far too much importance. Source material this large needs to jettison as much as it can, and that means making hard choices, but here, it seems as though McEleney was trying to keep as much as he could. It’s a noble effort, but it did more harm than good.

The same could be said of the direction by Tyler Dobrowsky, who has thrown everything but the kitchen sink onstage. With that approach, statistically speaking, you’re going to get a few hits, but the misses — like that paper cutter Guillotine — take the production dangerously close to camp. Some of the performances — like Matt Clevy’s Marquis and Rachel Dulude’s Miss Pross — ad a welcome bit of comedy to an otherwise deadly serious evening, but they’ve been directed in a way that causes them to venture so far from what some of the other actors are doing that it seems as if they’re not even in the same play.

And now we’re back to the library, because by the time the Revolution began, and books were flying from the shelves, actors were fighting invisible people in slow motion, and lines were just being thrown out in a way that I’m sure was supposed to seem chaotic, but really just played as comedic, I couldn’t for the life of me figure out who this production is supposed to be for. There are definitely very good reasons to mount this story, but setting it in this particular Providence location (similar to what Trinity did with The Crucible and Little Shop of Horrors — it’s starting to feel like pandering) seems to be championing the revolutionary power of books only to then … tear apart the books? The whole endeavor seems rather pretentious, and most of the tactics used to convey the bigger moments of the plot come across as tricks rather than organic innovation.

Listen, I love turning a table and a few chairs into a horse and carriage as much the next guy, but if that’s the way you want to go, you have to carry that through in every aspect of the show. The costumes by Toni Spadafora start out as street clothes as we open the show in the library and are led to think that this is the Elevator Repair Service method (their production of Gatz was eight hours long, set in an office, and featured a group of actors as characters reading The Great Gatsby as they performed it), but then we start seeing more literal machinations — period costumes, gorgeous lighting by Kate McGee, and other surprises that were welcome for their ability to keep us awake, but don’t help to create a cohesive production.

Trinity deserves some praise for not simply producing the region’s 87th production of Much Ado About Nothing, but I wish they had given this Dickens tome to one of the playwrights they have a relationship with along with instructions to modernize it or deconstruct it (or just set it on fire), or to a director who was more comfortable with letting the brutal parts of the story leave a longer-lasting mark than a paper cut. This production seems designed to make us feel something, but not very much of something. If you say you want a revolution, you’re going to need to be more specific.

A Tale of Two Cities runs until Mar 22 at Trinity Repertory Company. By Brian McEleney based on the novel by Charles Dickens; Directed by Tyler Dobrowsky. 201 Washington St, PVD. For tickets and more information, visit trinityrep.com or call 401-351-4242.