Bilow’s Law of Twitter: “No worthwhile ideas can be expressed in 140 characters, and even fewer in 280.”

My public journalist Twitter account (@MikeBilow) was created in 2015 by which time Twitter was fairly mature, although still long before the 2016 election and 2020 pandemic that saw social media sink into a swamp of misinformation and disinformation. For several years, I’ve been the maintainer of the Motif Twitter account (@MotifMagRI) that is an important on-line presence for the magazine.

I created my private personal Twitter account in 2008 when the service was less than two years old and mostly seemed to cater to attendees of the South-by-Southwest Festival. In those days, few had mobile web access and most users interacted with Twitter via text message. More than 14 years later, since what was by technology standards the paleolithic era, the ice age has ended and the glaciers have receded.

To give some sense of time scale, Twitter antedates both the Apple iPhone (2007) and Google Android (2008), which brought mobile internet to the masses. Although mobile internet existed before then – I had a Windows Mobile “Pocket PC” in 2006, replacing a Palm VIIx used for years earlier – it was an inconvenient rarity. For example, web sites were only accessible on the Palm if a “Palm Query App” was designed specifically for the site, and I wrote the PQAs for both The Providence Journal and The Boston Globe. By 2009, either I gave up on Windows Mobile or it gave up on me, and I switched to early Android then at version 2.0.

Nobody had any idea then where social media would go. The sector was dominated by MySpace (founded 2003) from 2005 to 2009 and then by Facebook (founded 2004), but neither was mobile-friendly. Early competitors dropped away: LiveJournal (founded 1999) was sold to a Russian media owner by 2007.

The model for most social media was the “blog,” shortened from “web log” and occasionally even spelled with a leading apostrophe (‘blog) to indicate the elided letters. A blog entry was an essay, usually at least a few hundred words, formulated with thought, care, and editing. Readers could subscribe to someone else’s blog and reply, usually in full sentences formed into paragraphs. LiveJournal turned this into an automated formula where everyone subscribed to the blogs of their friends and could interactively reply.

What Twitter revolutionized was that it was the first social media site intended to be used primarily on mobile, limiting the size of each post to the emphatically anti-blog-like 140 characters of a text message. Go to a show or a concert, or happen to be present at a newsworthy incident at the right time and place, and the place to tell others about it has been Twitter. Everyone with a cellular handset that could handle text-messaging could be a Twitter author in an age before mobile apps, let alone before app stores. By 2020, mobile internet access was so ubiquitous that text-message access to Twitter was discontinued in most of the world.

By emphasizing text as its medium, Twitter was going against the grain from inception. Multimedia seemed the wave of the future, with MySpace and its fellow travelers embracing music, photos, and videos. Eventually entire non-text competitors developed such as Vine, an antediluvian precursor to TikTok with content limited to six-second looping videos, that was bought by Twitter in 2012 and shut down in 2016.

A lot of ideas just collapsed in failure, and the Wikipedia category for defunct social media lists 134 named entities, surely a gross undercount. Quibi, for example, yet another video microblogging service, had the misfortune to launch at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic and burned through $1.75 billion of investor money before shutting down after only six months. Yet Twitter has survived, despite being consistently unprofitable during its entire existence.

Financially, investors have been losing confidence in Twitter, with its market capitalization (the stock price multiplied by the number of shares outstanding) crashing from $54.91 billion on Jun 30, 2021 to $34.55 billion on Dec 31, a 37% decline in the value of the company in only six months. A major reason for that lack of confidence is operating losses in 2020 of $1.14 billion and in 2021 of $0.221 billion. More seriously, long-term debt tripled from $1.76 billion at the end of 2018 to $5.32 billion at the end of 2021. The financial community knew this was not sustainable and the depressed stock price made it an attractive target to be acquired by a buyer, preferably one who was willing and able to shovel vast amounts more money into keeping it afloat.

Enter Elon Musk who announced on April 25 a deal to acquire the entire company for $44 billion. He is, among other things, the 7th most-followed user on Twitter (@elonmusk, 86.3 million), neatly squeezed between Taylor Swift (@taylorswift13, 6th, 90.3 million) and Lady Gaga (@ladygaga, 8th, 84.5 million). Widely recognized as the richest person in the world with an estimated net worth of $252 billion according to the Bloomberg Billionaires Index (well ahead of Amazon founder Jeff Bezos in second place at $164 billion), Musk has been involved in running numerous businesses ranging from electric car maker Tesla to aerospace contractor SpaceX. However, he has also too often made public comments that called his judgment into question, including tweeting that children are “essentially immune” from COVID-19, an objectively false statement that almost resulted in his Twitter account being suspended. Musk’s consistently strange tweets were themselves recently the subject of an article in The Guardian, a well-respected UK newspaper, under the headline “Chaotic and crass: a brief timeline of Elon Musk’s history with Twitter.”

Notably, Musk successfully defended himself in a libel trial brought by Vernon Unsworth, a diver who had been instrumental in the rescue of boys trapped in a cave in Thailand, whom Musk in a tweet called a “pedo guy.” According to Reuters, “…the jury was apparently swayed by the arguments put forth by Musk’s attorney, Alex Spiro, who said the tweets in question amounted to an off-hand insult in the midst of an argument, which no one could be expected to take seriously. ‘In arguments you insult people,’ he said. ‘No bomb went off.’… U.S. District Judge Stephen Wilson had said the case hinged on whether a reasonable person would take Musk’s Twitter statements to mean he was actually calling Unsworth a pedophile.” The legal community considers the dispute precedent-setting as the first jury verdict about the consequences of a tweet.

Musk took advantage of the depressed price of Twitter shares and began buying up stock in January 2022, disclosing in a required filing with the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) (known as a Schedule 13D) only on April 4, after the end of the quarter, that he had acquired 9.1% of the company for $2.64 billion, making him the largest shareholder. By keeping his activity secret as long as he could until the required disclosure, Musk got a huge bargain, implying a market capitalization of only $29.0 billion. Presumably the entity created by Musk to finance the purchase of the company at a reported total price of $44 billion would pay 9.1% of that, or $4.00 billion, to Musk for his existing shares, allowing him to personally pocket a cash profit of $1.36 billion.

The SEC previously fined Musk for what he considered a cannabis-inspired joke in 2018 that he would be buying up all outstanding shares in Tesla to take it private at $420 per share, an announcement that many investors took seriously enough to move the stock price. Musk and Tesla each paid a $20 million fine and were required to vet in advance through lawyers any future statements that could affect the market. Just this morning (April 27), a federal judge came down hard on Musk who was seeking to get out from under what has come to be known as his “Twitter sitter” restriction, writing that “Musk, by entering into the consent decree in 2018, agreed to the provision requiring the pre-approval of any such written communications that contain, or reasonably could contain, information material to Tesla or its shareholders. He cannot now complain that this provision violates his First Amendment rights. Musk’s argument that the SEC has used the consent decree to harass him and to launch investigations of his speech is likewise meritless and, in this case, particularly ironic.”

Twitter has spent years trying to navigate between what should and should not be acceptable to post on the site, a few weeks ago being drawn into a controversy about Adm. Rachel Levine, the head of the US Public Health Service, who identifies as a transgender woman and is the first openly transgender American to hold commissioned four-star rank. The Babylon Bee, a Christian-themed satire web site, tweeted that Levine was their “man of the year,” and their Twitter account was suspended when they refused to delete the tweet; at the same time, Twitter allowed a tweet from Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton that said “Rachel Levine is a man.” Such inconsistency has exposed Twitter to substantial criticism and accusations of hypocrisy.

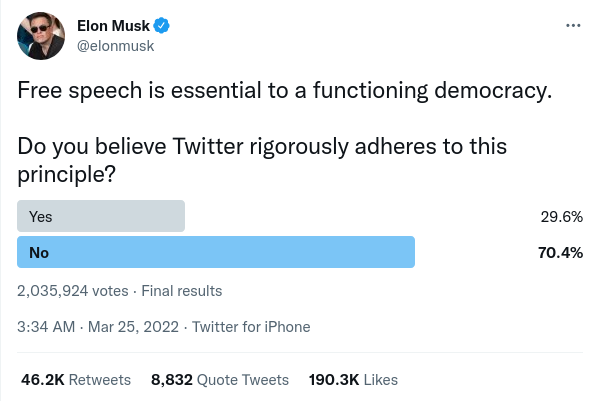

On March 25, shortly before disclosing his large acquisition of shares, Musk posted a poll: “Free speech is essential to a functioning democracy. Do you believe Twitter rigorously adheres to this principle?” resulting in 29.6% yes and 70.4% no with 2,035,924 votes. The next day he replied to his own poll: “Given that Twitter serves as the de facto public town square, failing to adhere to free speech principles fundamentally undermines democracy. What should be done?”

No one is entirely sure what motivated Musk to buy Twitter, but it is generally assumed that he wants to dial down its content moderation policies. “If you’ve been paying attention to how things work in our plutocratic society, this turn of events won’t surprise you. The arsonists routinely cosplay as firefighters,” wrote Anand Giridharadas in a guest essay for The New York Times.

Musk appears to have already breached the non-disparagement clause of his acquisition agreement with the board of directors by publicly attacking two of the top lawyers at Twitter. Getting the deal to completion requires jumping over a number of hurdles, including convincing regulators to allow it and the basic task of convincing shareholders to accept his offer price, and to accomplish both he needs to maintain sufficient self-discipline to keep his mouth shut. The current stock is trading below Musk’s offer price, a clear signal that the market has grave doubts that the deal will really happen: in theory, someone could buy the stock today and wait for it to be acquired at the higher price, which would be a slam-dunk as long as the acquisition goes through.

Serious concerns about privacy and security have been expressed from the tech community about what seem to be Musk’s intent to de-anonymize Twitter users and publish internal algorithms as open source, according to Carly Page on Techcrunch. The Electronic Frontier Foundation, a leading advocate for personal liberty in technology, called on Musk to reaffirm the previous commitment by Twitter to the Santa Clara Principles, published in 2018 to protect the transparency and accountability of “content moderation at scale,” also endorsed by Apple, Facebook (Meta), Google, Reddit, and Github.

I’ve been outright threatened on Twitter because I said that I thought it was reasonable for schools to require students and employees to wear face coverings in the pandemic, and this resulted in claims that I therefore supported “child abuse” and deserved to die. I don’t throw around terms such as “hate speech” lightly, but if that doesn’t qualify then nothing does. Telling me that I deserve to die may not technically be an illegal threat, but is at best on the very edge skirting First Amendment protection and arguably is outside it. Just because an incitement is not criminal does not imply it is harmless: It would be absurd for the standard of review to be the same for criminal charges and social media bans. While I recognize that someone saying that I deserve to die is not necessarily a criminal threat and may be protected by the First Amendment, it can have very bad real world consequences that justify it being prohibited on social media.

Such incitements can motivate people to undertake clearly criminal acts. While the decision to progress to crime is primarily the responsibility of the one committing it, the party making the incitement has responsibility it would be wrong to ignore. Conspiracy theorists who claimed that a pizza restaurant in Washington DC was a front for senior Democrats including the Clintons abducting children to extract adrenochrome from their blood to be used as an elixir of youth, commonly known as “Pizzagate,” did in fact motivate a man to cross state lines and show up with a rifle in a deluded quest to rescue children held captive in non-existent subterranean tunnels, for which he ended up in federal prison. A woman who believed that the Sandy Hook shooting was a hoax, encouraged by conspiracy theorist Alex Jones on InfoWars, made death threats against the parents of the dead children, for which she also ended up in prison.

Twitter is particularly important to journalists because it is their primary means of interacting with each other. I have regular exchanges with writers and academics, and this is very useful and valuable. The key to effective use of Twitter is to be aware of the sources: I know the difference between getting updates from the Kyiv Independent (@KyivIndependent), an extremely trustworthy and reliable on-the-ground news reporting service, as opposed to random trolls. Official entities are on Twitter, ranging from the ministries of foreign affairs for both Ukraine (@MFA_Ukraine) and Russia (@MFA_Russia) to embassies of countries to each other. Both the Israel Defence Force (@IDF) and the al-Qassam Brigades of Hamas who launch terrorist rockets from Gaza are on Twitter (using various accounts that are often suspended), sometimes interacting with each other to exchange public messages directly. From a news point of view, there is no substitute for this stuff.

At one point I considered joining Gab.ai, an alternative to Twitter that explicitly claims no censorship or restrictions of any kind. In theory this appealed to me, but actually looking at the site made clear that is a refuge for those thrown off Twitter, with the practical result that most of the traffic is from literal fascists, neo-Nazis, white supremacists, and similar people with whom I have no desire to be associated and even less desire to interact. Twitter is valuable to me because it is not Gab.

I understand that for someone who is an infrequent user of Twitter, it seems to be a flat swamp of people screaming at each other. Much of my responsibility as a journalist is to learn how to tell these apart and sift through these sources, applying my own knowledge and expertise. Just because there are some crazy people (or even a lot of crazy people) does not mean they are all crazy people.

Whether Musk ends up owning Twitter or not, substantial backing away from content moderation would likely destroy it, running it into the ground and rendering it as worthless as MySpace. Economists see the value of social media in the “network effect,” meaning that each user finds it more valuable because of the presence of other users. The term originated with the invention of the telephone: What value is a telephone unless there are people to call? In Musk’s utopian libertarian free-for-all model of social media, all of the sane users would be driven away.

I remember exactly where I was on August 9, 1995, because that was the day of the first dot-com initial public offering: Netscape. By chance I was attending a cookout, and everyone wanted my opinion on it as the “internet expert.” My advice was that I could not understand why the market had valued the company at $2 billion when it had no business model to generate income, and its sole activity at the time was to make software, the web browser, they gave away for free. It took about five years of riding the roller-coaster, but eventually the market figured out that I had a point.

Twitter is a private company owned by its shareholders, and if they want to sell out to Musk then this is their right. Certainly the world has no reasonable expectation that investors will continue to throw money into the firebox indefinitely to keep the fire lit. But there is no law of conservation of money: it can be created or destroyed.