When Amie Souza Reilly and her family buy a New England home in August 2014, the real estate agent forewarns them about the two brothers next door. They were “nosy but mostly harmless,” the agent says. Reilly wonders, “Did she emphasize mostly?” The house promises suburban bliss. A tiny office with a string light. Hardwood floors. A patio of old bricks. Then Reilly writes, “For the first three years we lived here, we were stalked.” You read Reilly’s Human/Animal [WLU Press, April 2025] with the suspicion that something awful approaches. Then you realize something already lurks right next door. In the open window. On the edge of the property. Following you on the train. Banging on your car door. What follows is a slow escalation from mildly strange behavior to a three-year nightmare, breaking the boundaries we uphold in community. As the twists keep coming, reading Reilly’s experience is genuinely creepy — you can only imagine what it was like to live through the events themselves.

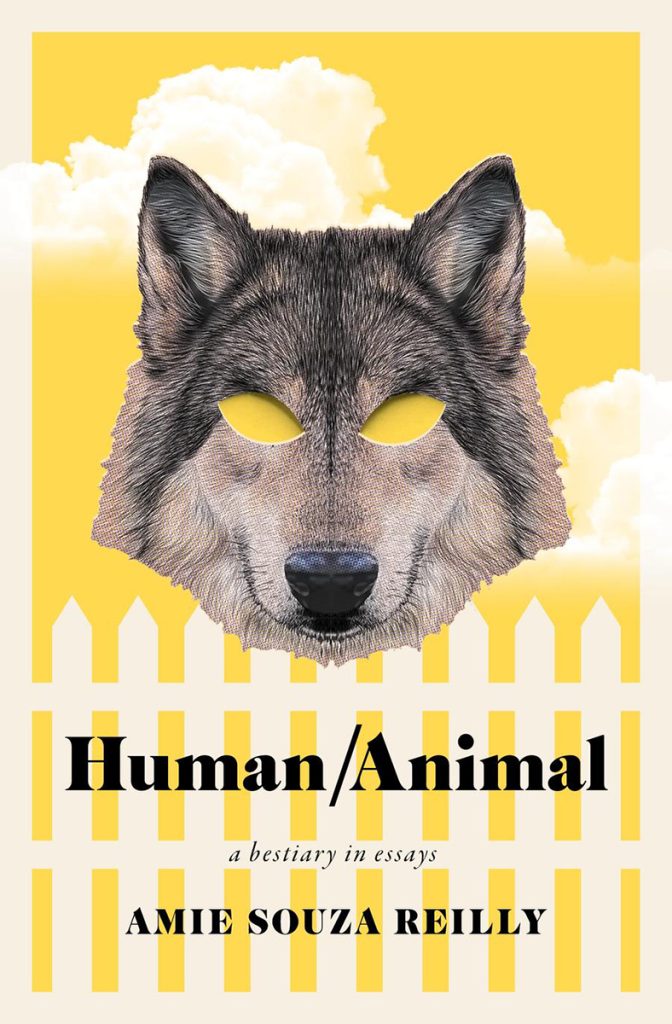

Reilly creates her work in nearby Connecticut as the Writer-inResidence and Director of Writing Studies at Sacred Heart University. As a visual artist and multi-genre writer, Reilly could offer horror on its own plate, but she delivers something much cooler. During COVID, Reilly talks about her family’s running word game, “making a list of all the animal names we use as verbs.” Human/ Animal replicates their game, weaving in Reilly’s beautiful animal illustrations as she redefines their names. A seal is more than a mammal, but also, Reilly defines “Seal: v. To close (with a seal)… In elementary school in the late ‘80s/ early ’90s, we swapped valentines stamped with the wet-sounding acronym SWAK, which meant sealed with a kiss.” Reilly keeps looking for hidden meanings, not only in the animal kingdom but in her fear. Even though her book focuses on violence, Reilly’s writing remains playful, collaging visual art and slowburn horror into its own strange creature. You thumb through Human/ Animal like an illustrated children’s book, except Freddy-Kruegerneighbors also haunt the edges.

Human/Animal is a clever assessment of American entitlement and male violence, while the two men in “matching red hats” pace around Reilly’s property and body. The brothers own another huge house, looming outside of town. But they want Reilly’s home, too. As the brothers stalk Reilly’s family, she questions her own behavior, second guessing her intuition while protecting her young child. Is she overreacting? Why is she afraid anyway? Reilly shows how the world shoulders women with the responsibility of those who hurt them, no matter who they are. She remembers her daily commute on the train when she was younger. The conductor points out a man who followed her, noting that they pulled him off the train for not having a ticket. He lectures her to be more careful, and she turns “red-faced with shame because I should have known better, and then I thanked him.” Like the final girl in Halloween, Reilly is made into “a woman scared of a man she should be afraid of, but no one, at first, will believe her. Until it’s too late.” Human/Animal shows how women are socialized into politeness, raised with the fear of overreacting, even when danger screams in your face.

Reilly describes the brothers alongside pop culture like The Texas Chain Saw Massacre and Marina Abramović’s performance art, then questions what it means to live among other people at all. We assume we live within solid boundaries, but what happens when someone disregards them? Who protects you? Reilly carefully spotlights the limits of policing, how our (friendly) neighbors help when wolves scratch at the door. But if Reilly wants to protect her home, she also wonders about the problem of owning property at all on colonized land. Reilly addresses American history, not only through the strange neighbors but through her own whiteness. When she tells her story, she also laments speaking in English, “[h]ow language can be violent, how mine is a language of exploitation, which means I cannot communicate without harm.” When she stares back at the people staring inside her house, Reilly wonders if there is any difference between her and her stalkers. Her insight is generous and sensitive, even while staring down violence. Her curiosity as a writer makes Human/Animal into a transfixing horror story, especially as nonfiction. I recommend her book to anyone who feels stumped at how to live alongside our wolves and remain deeply human. •