For over two hours on Wed, May 13, Jim Skeffington, principal representative of the new owners of the Pawtucket Red Sox AAA-level minor-league baseball team, faced a critical but generally polite crowd of 30 to 35 people at an open forum organized and moderated by Greg Nemes at the Design Office in Providence. In his introduction, Nemes said that, while all issues including financing were legitimately on the table for discussion, his own interests were in the urban design questions implicated by building a large sports and entertainment structure on the bank of the Providence River. “Discussions of design of the ballpark may seem like putting the cart before the horse, but both discussions can be useful at this time,” Nemes said.

For over two hours on Wed, May 13, Jim Skeffington, principal representative of the new owners of the Pawtucket Red Sox AAA-level minor-league baseball team, faced a critical but generally polite crowd of 30 to 35 people at an open forum organized and moderated by Greg Nemes at the Design Office in Providence. In his introduction, Nemes said that, while all issues including financing were legitimately on the table for discussion, his own interests were in the urban design questions implicated by building a large sports and entertainment structure on the bank of the Providence River. “Discussions of design of the ballpark may seem like putting the cart before the horse, but both discussions can be useful at this time,” Nemes said.

To his credit, Skeffington stated his case effectively without being baited into disputes over matters of opinion. He opened by saying that he had worked as a lawyer for 14 years for the Boston Red Sox and became involved in purchasing the team on their behalf from the widow of long-time owner Ben Mondor, but the Boston organization decided that they had other uses for the capital and encouraged him when he expressed interest in acquiring the Pawtucket team himself through a consortium that he put together to fund the acquisition.

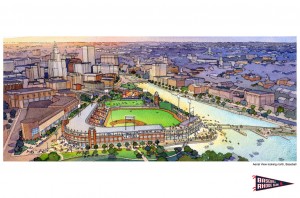

Because of the forum venue – the Design Office describes itself on its website as “a place for independent designers in downtown Providence” – the mix of attendees was heavy with architects and others, some identifying themselves as teachers at the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD), who strongly condemned replacing the planned public park with a large building and who asked about sustainability, energy efficiency, environmental footprint and even psychological effects of dividing the city and harming walkability. Skeffington defended the design itself, saying that about 3 acres would be “greenspace” that, except during actual game play, would be publicly accessible year-round. He also said that he would like to see the land between Point Street and Clifford Street used as a public park instead of other purposes such as an electrical power sub-station that he thinks would be very inappropriate in such a prominent location. If that additional land could be used as a park, he said, the resulting amount of greenspace would be only 1.8 acres less than what would result from not building the stadium at all. (In some rural towns in the state, 5 acres is the minimum buildable house lot.)

His response on the public park amounted to saying that, whatever its other merits, a “passive” use of space, such as a park, could not itself employ anyone or create economic activity. He was blunt that the alternative to moving the team to Providence would be to relocate it out of Rhode Island, saying that 400 or so jobs, amounting to what he estimated are 250 full-time equivalents (FTEs), would go with it. He explicitly said that the team had already received unsolicited offers from four out-of-state communities proposing total public financing of construction and relocation costs, which he said would be significantly more profitable if the team owners were looking primarily to maximize profit.

Skeffington repeatedly cited as examples Charlotte and Durham, both in North Carolina, where, he said, construction or renovation of minor-league baseball stadiums served as a catalyst for economic activity. He predicted that such secondary effects would produce “1,000 jobs across the street” much as he claimed had happened in Durham, where the presence of Duke University is comparable to the role of Brown University in Providence, but he conceded that there were “no guarantees” of such effects.

Of course, North Carolina is doing far better economically than Rhode Island in general, and the Charlotte metropolitan area (which extends across the state line into South Carolina) with 2.4 million people is the 22nd biggest in the nation, between Denver (21st) and Pittsburgh (23rd) that have seven major-league teams among them (MLB Colorado Rockies, NFL Denver Broncos, NBA Denver Nuggets, NHL Colorado Avalanche, MLB Pittsburgh Pirates, NFL Pittsburgh Steelers, and NHL Pittsburgh Penguins). Although the Charlotte Knights are a minor-league baseball team like the PawSox and compete in the same league, Charlotte is already an economic powerhouse that has been granted major-league sports expansion franchises three times in the last 30 years: the NFL Carolina Panthers in 1995, the NBA Charlotte Hornets in 1988 (that moved in 2002 and now play as the New Orleans Pelicans), and the NBA Charlotte Hornets in 2004 (that were first named the Bobcats when they replaced the original Hornets). In other words, Charlotte is something of a baseball outlier, and is arguably the largest metropolitan area in the country without a major-league baseball team. By contrast, the Providence metropolitan area, which extends into Massachusetts, with 1.6 million people is the 38th largest in the nation, behind Virginia Beach-Norfolk-Newport News (37th).

Skeffington said several times during his presentation that the strongly negative public reaction to the initial proposal – “Opinion: PawSox Stadium Proposal – Rushed and Opaque,” May 6, 2015 – meant that plan was now “off the table,” and that the team is in confidential negotiations with the state political leadership that he expects to be concluded within days. Although the negotiations are confidential until their conclusion, he emphasized that, if the negotiations are successful, the resulting proposal will be fully public and he would encourage open hearings and debate about whether it should go forward. He said that “if I were a betting man” he would set the odds about “50/50” that these confidential negotiations will produce any proposal at all. He said that of the 30 AAA-level minor-league baseball teams, 27 play in government owned stadiums (including McCoy), and the “typical” financing model for professional sports facilities was 20-30% private money and the remaining 70-80% public money. In response to my question whether the team would agree to put the proposal to a voter referendum, he said that time constraints would make that impossible because the team wanted to be able to begin construction by December 2015, and this required concluding a deal within the current General Assembly session expected to end in June or possibly at a special session shortly afterward.

I admit that Skeffington changed my thinking on major aspects of the project about which I have expressed skepticism in the past. A number of attendees at the forum clearly regarded the move out of Pawtucket as their main objection, holding preprinted signs expressing their desire to keep the team there and speaking about the strength of tradition at McCoy Stadium, citing the famous 33-inning longest game in baseball history. I have said – “Opinion: Questions Surround the PawSox Sale,” March 2, 2015 – that one important practical advantage of staying at McCoy is that it is already paid for, but Skeffington said that renovating McCoy was where the new owners started their thinking but rejected that option because their architectural consultants determined that it would cost $65 million to repair the old ballpark, essentially a complete tear-down and rebuild including foundation and girders, and even then he said it would be a much less than ideal facility. For example, his new stadium as proposed would have a capacity comparable to McCoy of about 10,000, but every seat would be “close to the action” with the first row no more than 12 feet above the field and the seating only 20 rows deep. The new stadium would also feature a “premium club restaurant” with about 150 seats, advanced medical facilities for Boston Red Sox players and other athletes undergoing rehabilitation and physical therapy, an expanded open berm where people could watch games from their own lawn chairs, and other amenities. An important concern, he said, is that about half of the attendees of games come from Massachusetts, so being close to the Providence railroad station served by the MBTA and other public transit would be an enormous advantage. He said that the consultants working for the team found that there were over 12,500 existing off-street parking spaces within a 10-minute walk of the proposed stadium site before counting an already-planned 2,000-car garage unrelated to the stadium project behind the Garrahy Judicial Center and a 650-car garage that would be part of the stadium project. I’m prepared to give him the benefit of the doubt on the unsuitability of staying in Pawtucket.

Skeffington said that Brown University is supportive of the new stadium, an absolutely critical matter because almost half of the land needed is owned by Brown and one of its buildings would have to be demolished as it would otherwise be situated in left field. Because the new stadium is designed to accommodate football and other sports as well as baseball, he said that Brown is excited to take advantage of the opportunity to relocate its five games per year from its facility on Elmgrove Ave in Providence, which is situated in a solely residential area that has produced much friction from neighbors. Likewise, he said that the University of Rhode Island is facing $20-30 million costs to renovate its existing stadium in Kingston, and could draw considerably more than the current 3,000 attendees per game by playing instead in Providence where they would be more accessible to alumni.

Ultimately, I think Skeffington made a good case for the location and design of the stadium, despite the ridiculous center-field replica of the Block Island Lighthouse that makes the entire thing look like a miniature golf course. The principal designer is Populous, whom he described as the acclaimed “guru” of the modern ballpark including Camden Yards in Baltimore and its prototype in Buffalo. I remain highly skeptical about whether a minor-league baseball team and stadium could be the “catalyst” for secondary economic activity that Skeffington claims to expect, and I regard the citation of the Charlotte and Durham examples as somewhat disingenuous because of the fundamentally different economic circumstances in North Carolina and Rhode Island. On the other hand, he could be right.

Without a concrete financial proposal, it is impossible to form, let alone express, any opinion about it. I am very glad that the earlier proposal, which I regarded as absolutely untenable, is completely out of consideration. If the ballpark is built, it has to be done in a way that makes economic sense on its own merits without wishful thinking about it being a “catalyst” for other development that could turn Rhode Island into North Carolina. Brown University and even National Grid may be on board, or at least not voicing objection, but the key stakeholders who have not yet been heard from are the taxpayers.

Pawtucket Red Sox official site for the new ballpark: http://supportoursox.com/ballpark-details/

The Design Office, 204 Westminster St, Providence, RI: http://thedesignoffice.org/