One week before COVID-19 caused Rhode Island to enter a state of emergency, the Cambodian Society of Rhode Island announced its plans for the Khmer New Year. Along the Pawtuxet River in Cranston, Buddhist monks from the state’s temples would bless attendees during a morning ceremony as local Cambodian families gathered to remember and honor their ancestors. At night, a Khmer dance troupe would perform as the featured act in an annual celebration intended to preserve a cultural heritage. With nearly 6,000 Rhode Islanders identifying as Cambodian in the 2010 U.S. Census and nearly 4,000 residents living in a household in which Khmer is spoken, their experiences differ across generations. The cancellation of the April event ushered in a year focused instead on community health and safety.

Between 1975 and 1979, an estimated 1.2 million to 2.8 million of Cambodia’s nearly 8 million people were murdered or starved to death under the Khmer Rouge. In the preceding period, from 1969 to 1973, the U.S. Air Force conducted covert bombing campaigns — Operation Menu and Operation Freedom Deal — which led to the deaths of an estimated tens of thousands of civilians. By 1980, half a million Cambodians were estimated to be living in limbo in refugee camps in Thailand. In a statement delivered to a U.S. Congressional subcommittee, a program director with the International Rescue Committee advocated for urgent assistance with their resettlement: “They are the survivors brought back from the edge of death… It would be too cruel and ironic a fate if they were to be abandoned and forgotten.”

In Rhode Island, thousands of Cambodian refugees found a new home, but little immediate refuge. Reports from the 1980s noted doctors declining appointments on account of language limitations and frequent victimization by landlords, employers and neighbors. Local community organizations started up to provide support and advocate for the new arrivals. Four decades later, Rhode Island today has the largest per capita Cambodian population in the country. At the start of another Khmer New Year, Motif’s Sean Carlson interviewed Andy Chao, president of the Cambodian Society of Rhode Island, about the organization’s evolution and community-based health outreach during the COVID-19 crisis.

Sean Carlson (Motif): From your beginnings as a resource for new refugees, how has the Cambodian Society of Rhode Island (CSRI) adapted to the needs of the community you serve?

Andy Chao: We were founded in 1982 to bring Cambodian refugees and their families together and to help them transition into life in America. As they began to stand on their own, we shifted more into cultural arts to help preserve and educate others about our Cambodian heritage. One thing that hasn’t changed over the years is our advocacy for members of the Khmer community. This past year, during the COVID-19 pandemic, we shifted our energy and efforts toward becoming a health resource as well. We now plan to further expand our mission to include more social work geared toward Cambodians locally.

SC: For those who came as refugees to Rhode Island, what effects have you seen from their traumas?

AC: The families who fled and came to the United States often missed out on their education and had undiagnosed PTSD after surviving genocide and war. In many cases, they were never taught how to effectively communicate with one another, and this only led to fractures and disagreements continuing for generations within our community. Families often don’t know how to handle conflict or find resolution, or how to use their communication skills to deepen how they understand one another. We see this worsened by the language barrier that exists today between Khmer elders and youth. We hope to be able to provide social workers who are bilingual in Khmer and English and can assist with therapeutic and meditative care. Our elders need closure. Many still live with the pain they experienced 45 years ago.

SC: This week marks the Khmer New Year. You usually celebrate the holiday with an event held at Rhodes on the Pawtuxet in Cranston. How have you had to adapt on account of the pandemic?

AC: Because of COVID-19, we haven’t been able to hold any community events or social gatherings. We cancelled our annual Khmer New Year celebration, annual community potluck, and annual community camping trip. These events usually bring in donations, so we’ve also faced financial struggles for the year. We’re fortunate to have an all-volunteer board so we’re able to function even with low funds, but the past year has been tough on everyone in our community so we haven’t expected too many donations. Thanks to the Rhode Island State Council on the Arts, we were able to acquire emergency funding to keep us afloat and upgrade our old technology to be able to host virtual meetings and events.

SC: But you’ve also taken steps to provide public health information and support within the community.

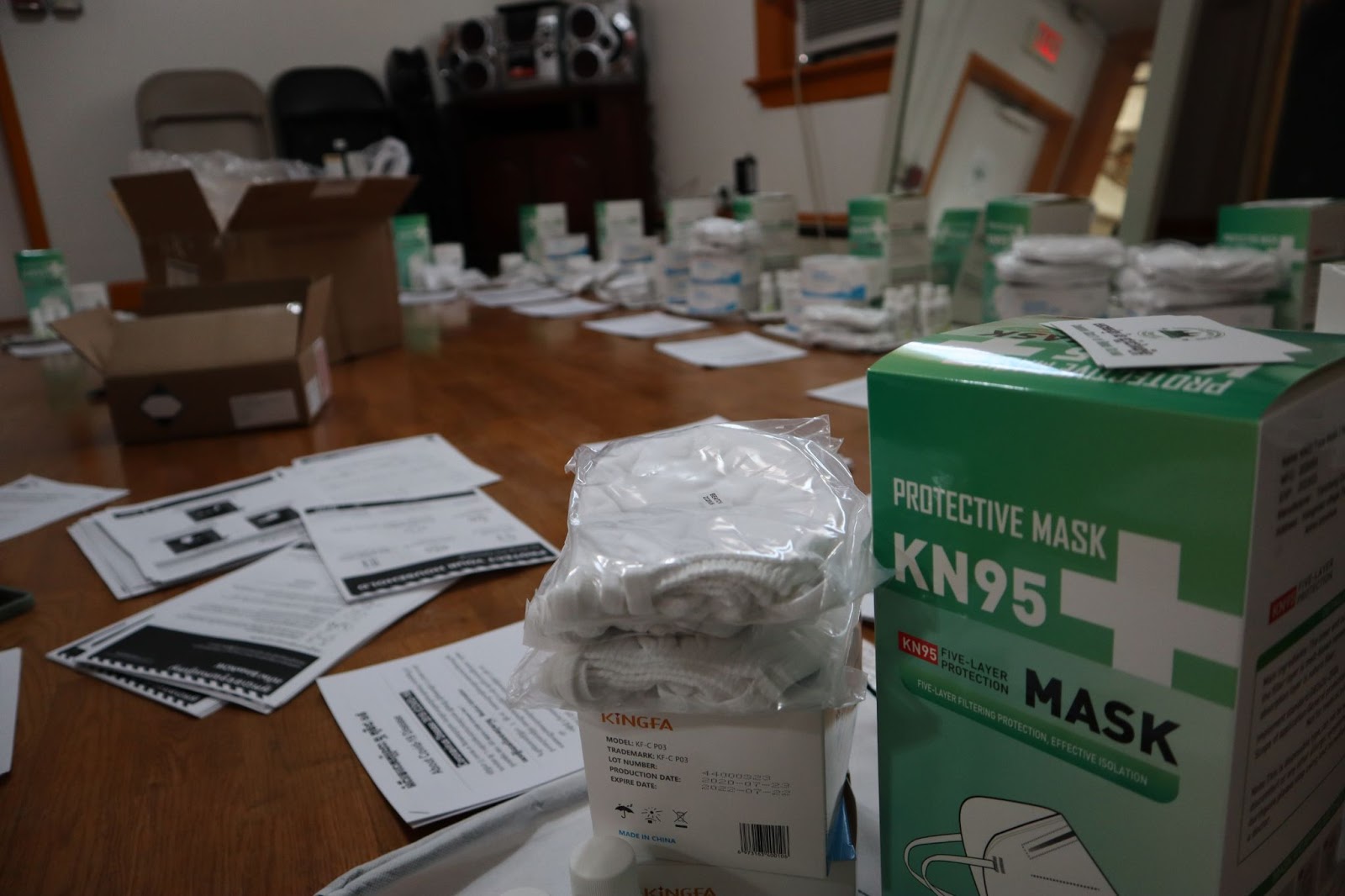

AC: We held multiple COVID-19 testing events at the heart of the West End of Providence. Collaborating with the West Elmwood Housing Development Corporation (WEHDC), we handed out almost 1,000 bags of adult masks, children masks and hand sanitizer within the Khmer community. One of our initiatives was to bring PPE to every Cambodian-owned business, and we counted nearly 60 — though we know we missed a lot. We translated the Rhode Island Department of Health’s flyers into Khmer, and we distributed hundreds of copies. We worked with Wat Thormikaram, the temple across the street from our office, to register Cambodian residents for vaccination appointments. And last winter we held a flu clinic as well.

SC: The COVID-19 testing events you’ve managed have been open to the public, not only to Khmer speakers or the Cambodian community. How did this initiative come together?

AC: One of our board advisors, Phanida Phivilay, acted as a liaison with the Department of Health. She connected us with the National Guard team who’s organizing COVID-19 testing, we chose a date and we set up our first testing event to welcome Khmer-speaking and other members of our local community. Every time we held another testing event, we improved based on what we learned from the previous one. Overall, we’ve tested around 400 people for COVID-19. Many Cambodian elders came into our office with no idea how to answer the questions required for testing. Without our translation and interpretation, it would have been difficult for them to be tested anywhere due to the language barrier. Being a center for the community, we were able to help folks who were scared to feel more comfortable.

SC: The Department of Health has published some COVID-19 materials in more than a dozen languages, including Khmer, but its testing and vaccination portals are available only in English, Spanish and Portuguese. What’s your process for sharing information in Khmer? How do you get the word out?

AC: We use the English versions hosted on the RIDOH website and hire translators to write up Khmer editions. We post these at local businesses and temples. We also include them with the bags of PPE we distribute. Word of mouth is especially important because that’s how news travels within our close-knit community. For many of our elders, because they left school early in Cambodia, they may not be able to read well even though they speak Khmer — and would rather learn from talking with others or listening to podcasts. It’s important that our flyers don’t only include words, but that our visuals speak for themselves.

SC: Are you also leading on any community initiatives around vaccination efforts?

AC: While we haven’t been able to provide vaccinations yet, we offer general support and answer any questions our community may have about the vaccination in general or about registering for updates or making appointments. We’re discussing with the Rhode Island Department of Health and the National Guard whether we can offer vaccinations, either at our temple on Hanover Street in Providence or in the West End Community Center’s gym since our office is so small. But we’re waiting on vaccine availability.

SC: What unique needs or sensitivities should be taken into consideration when discussing vaccination?

AC: We still see a stigma attached to Western medicine and practices. Some of this relates to drug abuse within our community as a way to cope with the PTSD and intergenerational PTSD of war. For refugees, medicines were not readily available when growing up in Cambodia. If they were available, they were expensive. As a result, many of the elders in our community weren’t educated about different types of medicine, and that lack of education can equal a lack of trust. We see that now with the COVID-19 vaccination. But the best way to address these hesitations is not just to force people to take it, but to help them understand what it is and how it works. We can’t look down on those who are uncomfortable with the vaccine and treat them like they are ignorant. This will only make members of the community less likely to ask the questions on their minds and eventually to warm up to the idea of getting vaccinated.

SC: We’ve discussed community outreach overall, but are there any personal stories you can share, too?

AC: One older Cambodian man and his family were referred to us by another organization who had difficulty communicating with him in Khmer. After being hospitalized with COVID-19, he had been discharged but didn’t understand what the next steps were with his care or how to get his vehicle back from hospital parking. We were able to speak with the hospital about his situation and ensure he faced no extra charges as a result of the confusion. Every two weeks, we checked up on him and his family and dropped off boxes of fresh groceries. Another time, a single mother with a toddler reached out to ask for help with getting masks for her child. Adult masks are easy to find, but you rarely see children’s masks.

SC: Given the difficulty of the past year, have any particular Cambodian-owned businesses stood out?

AC: While so many businesses have been shutting down during COVID-19, we want to highlight two new Khmer businesses: Pailin Cuisine (705 Cranston St., Providence) and We Stand Social Club (174 Taunton Ave., East Providence), which is a tattoo parlor and tea cafe. Both opened up despite the challenges and have been especially active in the community. We Stand even sponsored the West Elmwood Intruders youth football team and held a turkey and toy drive to help during the holidays.

SC: And how have you been processing recent incidents of anti-Asian vitriol and violence nationally?

AC: The recent spike in attacks toward Asians feels like history repeating itself. When Southeast Asian families came to the United States in the 1970s, we experienced a lot of racism, hate, and attacks — so much to the point where we even formed gangs to protect ourselves. It’s still not talked about a lot, and it’s a part of American history that many outside of our community seem to either forget or ignore. Anti-Asian hate is finally gaining mainstream attention, but our only hope is that we can see lasting action and support. When we were refugees, they had nothing to hate on us for, so focused on our physical appearance. Now, we’re scapegoated because of COVID-19. China is blamed for a pandemic that would have affected millions regardless of its origins, and somehow all Asians are facing repercussions.

SC: Thank you for sharing with Motif. Is there anything else you’d like other Rhode Islanders to know?

AC: We’re one of a few Southeast Asian non-profits that have long advocated for Cambodian and other communities: the Alliance of Rhode Island Southeast Asians for Education (ARISE), the Providence Youth Student Movement (PrYSM), and the Center for Southeast Asians (CSEA), which started out as the Socio-Economic Development Center for Southeast Asians (SEDC). Together with these organizations, we pushed for social justice and spoke up to represent voices that were going unheard. For decades, we’ve spread awareness and made steps toward reforming the systems that keep us marginalized.

More Posts by The Author:

Art in the Public View: Walking through RI’s street scenes

Some Latent Linguistic Irreverence: Alta L. Price on language learning while printmaking

At Home in the In-Between: Julia Sanches on migration and movement

The Power Wielded by Writers: Joanne Leedom-Ackerman on the fight for freedom of expression

The Nature We Build Around Us: A conversation with Connor Burbridge of Nuts & Bolts Nursery Co-op