Before 1952, Woonsocket was divided into five city council wards. After the 1952 Charter Commission finished its work, Woonsocket moved to the system it roughly has today, with seven at-large city council seats and an elected mayor. Instead of at-large seats, most cities use a district election model that ensures people from different neighborhoods will be chosen to represent the city evenly. How did Woonsocket get to this model, and 70 years later, what have been the effects of this change?

As Woonsocket entered the 1950s, it was a city in decline: The manufacturing base abandoned the mills and moved south to take advantage of workers in states and countries with more lax laws regarding worker safety and compensation. Woonsocket became convinced that their way of organizing city government was holding the city back. So, as Providence had done in the 1940s, Woonsocket formed a Charter Commission to modernize and streamline the government. This modernization would ultimately be accomplished by establishing a unicameral legislature of seven non-partisan, at-large city legislators and a “strong mayor” executive branch.

The establishment of a unicameral at-large city council was accomplished by doing away with the ward system. At present, all city council members are at-large, meaning that in any election, the top seven vote-getters become the city council. The candidates are also technically non-partisan in that they don’t have an official party affiliation.

Images compiled from data published by UpriseRI

As detailed in the Woonsocket Call on May 10, 1952, the chairs of the three political parties in Woonsocket presented their views on how to reconfigure Woonsocket’s government, with an eye towards redistricting the city. Surprisingly there was a broad agreement among the three party heads as to what was needed. Democrat John F. Doris, Republican Emile A Pepin, and Independent Kevin K. Coleman, as leaders of their respective parties in Woonsocket, expressed to the Charter Commission a series of good governance ideas.

These ideas included a “strong mayor” system of government (not a city manager) plus higher salaries for both the mayor, which should be a full-time position, and for city council members, as a means of attracting higher-caliber candidates, and several others.

Arguments against at-large elections, at least as they pertain to the school committee, were made by Thaddeus Piekos, financial secretary of the Woonsocket Teachers Guild, the teacher’s union. Piekos said that “at-large elections could result in the selection of five members from the same district with other school areas being overlooked as a result.” (Woonsocket Call, June 7, 1952)

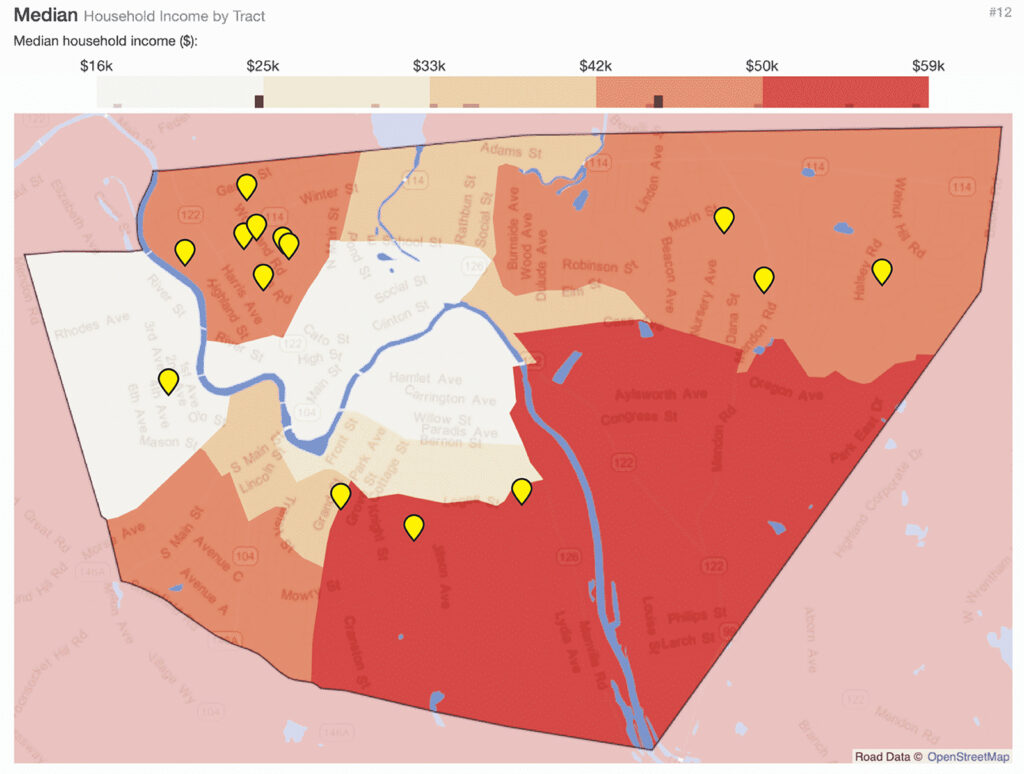

Sadly, the predictions of Piekos have been borne out by time. In the seventy years since the Charter Commission finished its work, political power has concentrated into three areas of the city. People of color and low-income people are not getting elected to office. Instead, wealth, power and whiteness dictate representation in Woonsocket.

The notes kept by the 1952 Charter Commission seem to have been lost to time. A records request made to Woonsocket City Hall yielded no results. The Woonsocket Historical Society has nothing about the 1952 Charter commission, and the Woonsocket Public Library was also unable to provide more than the Woonsocket Call articles and some historical books on the subject. All these organizations were extremely supportive in writing this piece.

[This version of Wealth, Power and Whiteness Still Dominate Representation in Woonsocket has been abbreviated; read the full version at UpriseRI.com]