As retail gasoline prices rise above $4.00 per gallon, a lot of misinformation and even disinformation is circulating purporting to explain this. Let’s try to get to the real reasons.

The historical peak for retail gasoline was in 2008 when the consumer price reached what would be $5.20 per gallon today, adjusted for inflation, and we are still far from that. According to the widely cited AAA tracker, as of Mar 9, the average retail price in RI is $4.287; it was $3.624 a week ago, $3.468 a month ago and $2.706 a year ago. Why?

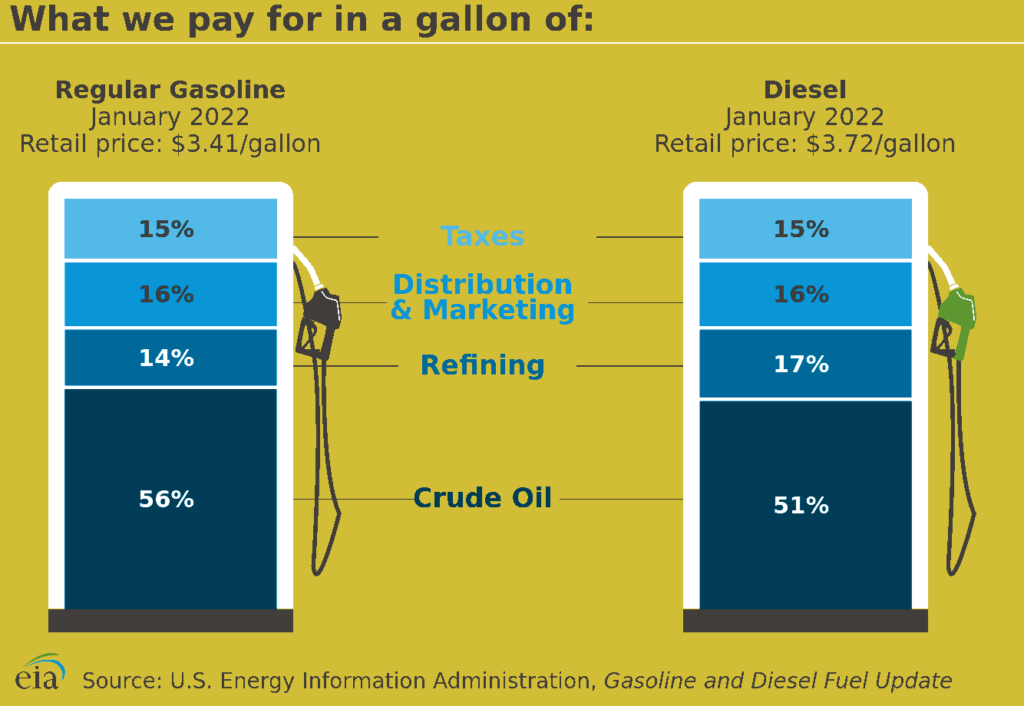

The gasoline price at the pump is 15% taxes, 16% distribution and marketing, 14% refining, and 56% crude oil, according to the US Energy Information Administration. (Diesel is about the same, although refining is slightly more expensive.) Crude oil, of course, is the big variable.

Crude oil is a commodity traded on the New York Mercantile Exchange (NYMEX) where its price is determined by open and public auction between buyers and sellers. Supply and demand causes the price to change: when there is an imbalance in favor of supply the price goes down; when there is an imbalance in favor of demand the price goes up.

In the market there are two main types of crude oil: West Texas Intermediate (WTI) and Brent, both of which are similar and easy to refine into useful consumer products such as gasoline. The primary difference is that WTI is the benchmark in the US and Brent is the benchmark everywhere else. Brent is the pricing benchmark for the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), an international cartel that tries (usually unsuccessfully) to manipulate supply. Sometimes one is cheaper than the other, but generally they track closely together.

Most of the trading action is in “futures,” which are contracts for the delivery of product some number of months in advance. Producers of crude oil can offer a contract now and buyers will pay cash to obtain the right to buy at a specific time and specific “strike” price. The cash can then be used to fund the production process, including exploring, drilling, mining, and transporting. Buyers are guaranteed future supply at a fixed price: if the market price of crude oil rises above the strike price specified in the contract, they can sell the contract itself at a profit.

What is essential to understand is that the price rises and falls based on the consensus expectations of the mass of buyers and sellers participating in the market. Trading futures contracts reflects not supply and demand in buying and selling of actual oil, but predictions about what the supply and demand will be in the future. Anyone can look up the current price of oil futures on the NYMEX. For example, at the moment, the contract for delivery of one barrel in April is $124.66 (-10.06% today), in May is $120.66 (-11.59%), in June is $116.50 (-11.96%), and so on. This means the instantaneous market consensus is (more participants believe) that the crude oil price will fall rather than rise.

Obviously, the recent invasion of Ukraine by Russia has spooked the oil market, but the actual cost of energy is not yet reflected in retail prices that are instead being driven by worries about the future.

The recent gasoline price spike almost entirely reflects market psychology and worries about the future. Existing markets have figured in the consolidated expectations of many buyers and sellers as to how difficult it will be to obtain reliable supply in the coming weeks and months, and distilled that down to price changes. Energy is inherently a worldwide concern and is fungible: Although the US has robust sources, shortages in Europe or Asia will drive up prices everywhere. No one can control the market, neither big oil companies nor governments.

Now that you know what really determines the price of crude oil, the major variable factor influencing the price of retail gasoline, what other oil-related ideas are true or false?

The US public assigns blame by preconceived assumptions, not facts

A YouGov survey asking “Who would you blame most for rising gas prices?” found that the public overall was evenly split, Biden 36% and Putin 35%. But there was enormous partisan polarization:

| Party | Biden | Putin |

|---|---|---|

| Democrats | 10% | 59% |

| Republicans | 70% | 16% |

| Independents | 40% | 30% |

The US is the world’s largest oil producer

About 15% of the world oil supply comes from the US, with Russia second at 13% and Saudi Arabia third at 12%. After that, Iraq is fourth at 6% and Canada fifth at 5%.

The US imports little crude oil from the Middle East and almost none from Russia

When the US imports crude oil, 61% is from Canada and 11% is from Mexico. Only 8% is from Saudi Arabia and 3% is from Iraq. Rounding out the top five sources of crude oil imports to the US, Colombia (in South America) accounts for 4%.

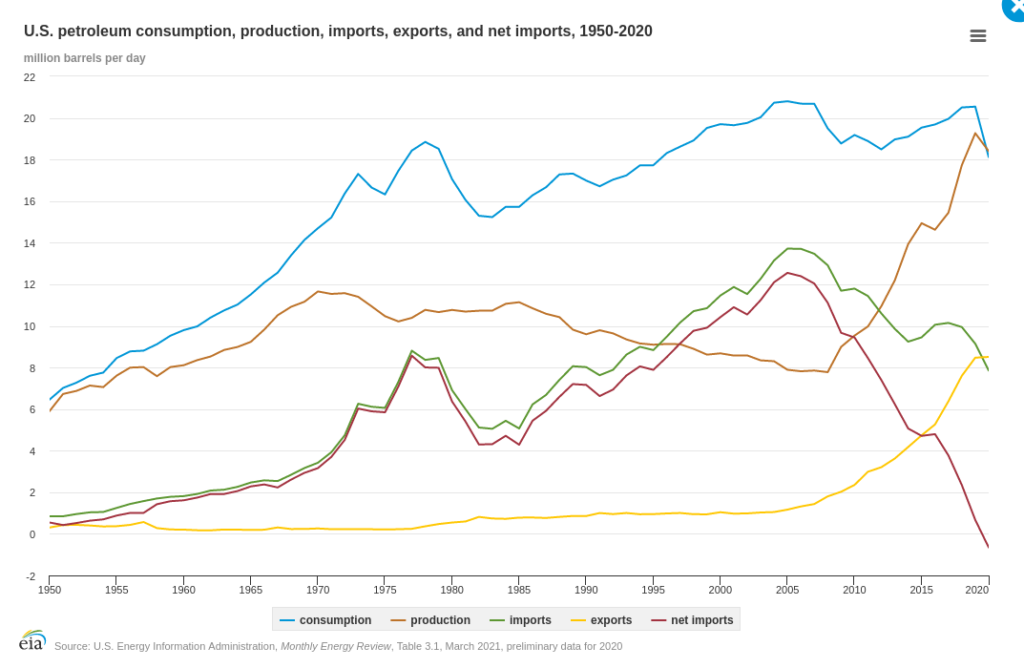

The US is a net exporter of oil and has been since 2020

Although the US imports more crude oil than it exports, so much of it is refined for export that overall the US exports more oil than it imports. In other words, the rest of the world is paying the US to employ its superior refining technology.

Different sources have different costs

Oil comes from a lot of different sources in different places. Some is harder to extract and some is easier, so the costs vary among these sources. As the market price falls, more expensive sources become unprofitable and are taken off-line; as the market price rises, more expensive sources become profitable and are brought on-line. The process of physically enabling and disabling sources of supply takes months, so it always lags behind demand.

There are also costs that vary geographically: labor is paid more in developed countries such as the US than in developing countries, so often leases remain unused for production simply because it is cheaper to produce oil outside the US. This is why, with crude oil prices at historical lows until recently, US oil production decreased.

Consumer behavior and demand is changed by price

When gasoline prices spiked in 2008, so many commuters in RI decided to switch to RIPTA instead of private cars that buses had to skip picking up passengers because they were already full. Unfortunately, much of RIPTA funding comes from the gasoline tax, so a decrease in demand for gasoline reduces funding for public transit.

Federal government policies have little effect on the price of energy

Criticism of the Biden administration for canceling the Keystone XL pipeline project, regardless of one’s view on whether the decision was correct, ignores the fact that no fuel would have passed through it until 2030 at the earliest, so far into the future that it has no current effect on prices or supply.

Similarly, controversy about shutting down the Canadian Line 5 pipeline under the Great Lakes has misrepresented it as a US federal government proposal somehow connected with climate change, when in fact it has been the State of Michigan concerned that the pipeline, in operation since 1953, poses a danger of leakage and widespread contamination of fresh water supplies.

Biden administration leasing policies are constrained by court orders

Ironically, a legal dispute over climate change has tied the hands of the Biden administration from issuing oil and gas leases. Estimating the “social cost” of carbon dioxide greenhouse gas emissions, the Trump administration set a valuation of $7 per ton on the grounds that effects outside the US did not have to be counted, while the Biden administration set $51 per ton after taking into account worldwide effects. Eleven states with Republican attorneys general sued to overturn the change, and a federal court blocked it. The practical result was to leave the federal government with no legally valid number, and therefore no way to evaluate applications, freezing the lease review process.

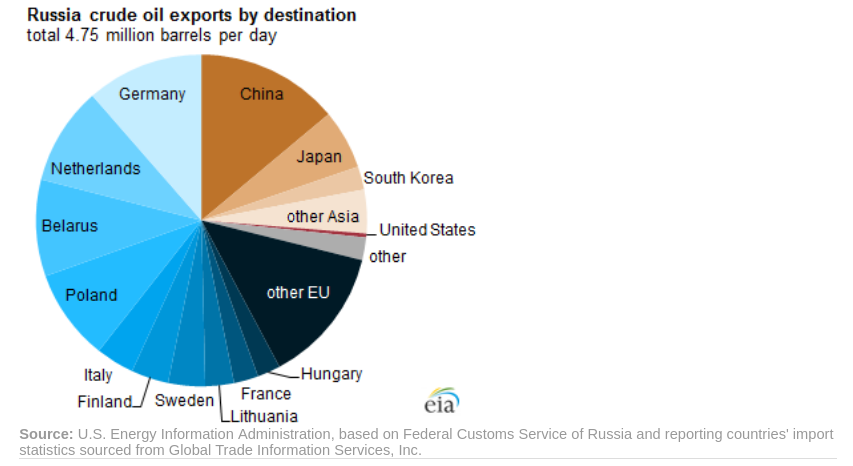

Europe has a huge problem because of dependence on Russian energy

While the US has the luxury of banning Russian oil imports as Biden did yesterday, Europe is far worse off depending on Russia for 40% of its natural gas and 25% of its oil. All European countries are not in the same position either: Russia supplies Poland with 67% of its natural gas but Ireland with only 5%. Experts estimate, that Europe could replace 85%–90% of Russian natural gas with some combination of imported liquified natural gas (LNG) shipped by boat, mostly from the US, and expansion of renewable sources. No one knows what the economic and political effects would be of a large cutoff that could result in sharp inflationary price increases and even rationing. Retail gasoline in most of Europe already costs more than the equivalent of $8.33 per gallon.

Russia faces economic devastation if Europe drastically cuts imports

Russia gets about two-thirds of its export revenues from energy, so any sizable reduction would result in severe damage to its economy, plunging the nation into real poverty well beyond what any sanctions could do by focusing on currency exchange and the banking system. The European Union’s stated plan to try to eliminate two-thirds of its energy imports from Russia by the end of this year is uncharted territory.