Halloween was a war against the dark, the dead, and the deities. In Celtic Ireland, where the tradition began, many people were druidic. They focused their worship on the spirits and gods of the natural world that they believed held their fate. In a world where their entire religion was based on nature and appeasing the gods to stay alive, the darkness of winter must have seemed like a sinister punishment. Halloween was a time of ritual and sacrifice to ensure survival until the next winter. As Dr. Kelly Fitzgerald, Head of UCD’s School of Irish, Celtic Studies and Folklore, states, “Halloween is the time of year that we face our fears because we’re going into the darkness.” It was a one-night war against the army of darkness, spirits, demons, and the devil.

Samhain

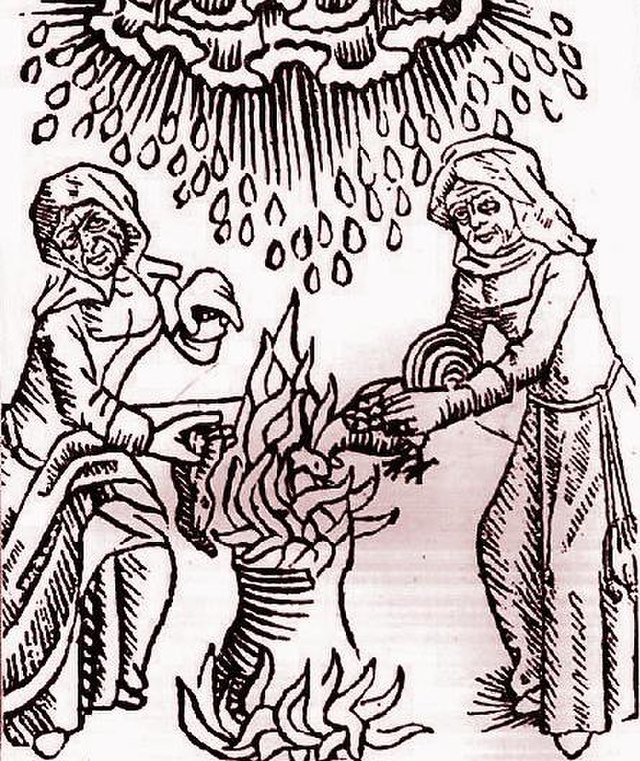

Halloween’s traditions began, around 2,000 years ago, with the Celtic festival of Samhain (pronounced sow-in). The pagan festival was intended to mark the end of harvest and predict if they would survive the winter. It was also a day when the veil between the corporeal world and spirit world became thinner. The shadows grow longer, trees converse in the wind, as though everything is preparing for the arrival of something darker. And it’s dark – oh, so dark. No wonder it felt like death and its demons had a chance to sneak into our world. Part of this was used as an advantage. The Druids believe that the presence of spirits among them could help Druids and Celtic priests predict whether or not they would survive the winter. They would use this time to give gifts to the gods. Large sacred bonfires were lit to fight against the dark. They burned crops and sacrificed animals to appease the Celtic deities. Costumes were worn, often with the skins or heads of animals, so that they would not be dragged to the world of death by an evil spirit. It was a war against the upcoming stillness of winter. When the celebration was over, they would relight their hearth with fire from the sacred bonfire to help protect them during the winter. Today, we protect our houses with smaller candle-sized bonfires, which we set in carefully carved gourds or pumpkins. We call these Jack-O-Lanterns, after a 19th-century Irish folktale, where an unfortunate fellow named “Stingy Jack” plays with the devil and loses.

Mixed Religions

As most traditions are in America, Halloween has become a mishmash of different historical celebrations. In 43 AD, the Romans conquered Celtic territory, and two of their celebrations began to mix with Samhain. The first celebration was a day in late October that the Romans called Feralia. Feralia commemorated the passing of the dead. The second was a celebration of Pomona – the Roman goddess of fruit and trees. Pomona is often represented by apples, which morphed into the practice of bobbing for apples. Around this time, people also visited from house to house, where they would pay respects to the dead ancestors of its occupants, in exchange for small cakes; similar to trick or treating today. The Catholic church took over some of the traditions of Samhain, seemingly trying to phase out the Pagan ritual. First, Pope Boniface IV designated May 13 to be All Martyrs Day, in honor of all Christian martyrs. Going as far as dedicating the Pantheon to honor them. In 1000 AD, the church designated November 2 as All Saints Day. Pope Gregory III expanded the original All Martyrs Day festival from May 13 until November 1, also designating October 31 as “All Hallows’ Eve.” From All Hallows’ Eve, the name evolved to Hallow’en, and what we know as Halloween.

Halloween in the US

Halloween was avoided by the Puritans who settled in New England. The new colonies had very rigid Protestant values that did not include ritualistic sacrifice and playing with spirits. In the early colonies, they began to have “play parties” to celebrate the harvest, tell fortunes, sing, dance, and tell stories about the dead. Even though celebrating autumn was popular, Halloween truly gained in popularity during the Irish Potato Famine when millions of Irish flooded into the US, bringing their Celtic roots with them. It wasn’t until the late 1800s that Halloween became more popular. Parties for fortune-telling, ghost stories, and pranks became far more common. By the 1920s and 1930s, Halloween became much like what we know it as today. Due to the baby boom of the early 1900s, the rituals became more child-centric, as commercialism came into play with its shiny candy bags and the rubber masks that your brain has inadvertently memorized the smell of. Halloween grossed approximately 12.2 billion dollars in 2023 in the US, making it the second-biggest holiday of the year, financially.

Though we center Halloween around children meeting strangers and accepting food from them, adults still love it, too. We wear costumes to scare each other, not the dead. We still bob for apples, though I doubt many know of the Goddess Pomona. In many cultures, like Mexico, with Dia De Los Muertos, the ritual is more tied to remembering your ancestors. Here in the United States, we eat candy, watch slashers, and stab pumpkins. To each their own. •

Image from Wikipedia Commons