There are a lot of things to like in Vault, the new crime film about the legendary 1975 Hudson Bonded Vault robbery from director Tommy DeNucci and producer Chad Verdi. The heist netted an estimated $31 million of loot from organized criminals who stored it in private safety deposit boxes. The acting is superb, the script is tight, and the production values are high, but ultimately Vault is a love letter to Providence as it was in the 1970s. It’s well worth seeing on the big screen while it runs at the Showcase in Providence and Warwick.

On the one hand, I felt really old at the premiere at the Showcase Cinema Warwick on June 6 because I seemed to be one of the few present who was alive during the 1970s, let alone remembered the decade. On the other hand, the accuracy of the sets and costumes was impressive, down to the ridiculous but historically accurate brown uniforms of the Providence Police, part of a misguided effort to make the cops seem more friendly. Seeing a coin-operated, rotary-dial telephone in a booth was a hoot. The classic cars, including a Ford Thunderbird and Chevrolet Camaro SS, were a treat. News footage, both real and simulated from the non-existent Providence “Channel 7,” opens the film. The music is outstanding.

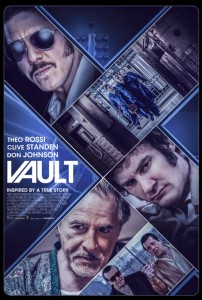

In the lead roles, Theo Rossi as Robert “Deuce” Dussault and Clive Standen as Charles “Chucky” Flynn are charming petty criminals who have known each other since their teenage years. They’re a great team, with the hotheaded Chucky often hiring the methodical Deuce to plan and execute complicated tasks – such as the Hudson Bonded Vault robbery.

Historical criticism aside, detailed below, Vault is highly entertaining. Samira Wiley in the role of Karyn, Deuce’s girlfriend, turns in an Oscar-worthy performance. Especially if you know nothing about the real history of the robbery, the film is a gripping crime caper with larger-than-life personalities, evoking a bygone era of romanticized mafiosi, wise guys, and “made men” that dominated organized crime – and it makes a plausible case for why that era ended as discipline broke down, the code of silence was successfully eroded by the feds, and organized crime became, for lack of a better word, disorganized.

Don Johnson is a chilling Gerry Ouimette, especially when his usual smile is traded for a momentary flash of anger. Chazz Palmintieri is an eerie Raymond L.S. Patriarca down to his mannerisms and distinctive staccato speaking style; Patriarca would say literally anything in the same emotionless tone, speaking just a bit more slowly than anyone else likely would, deliberately making it impossible to tell whether he was pleased or angry, something he consciously exploited to unnerve those to whom he spoke. In one critical scene, Ouimette asks to be “made” a full member of the Patriarca Crime Family, and is told that will never happen because he has no Italian ancestry, explaining Ouimette’s hatred for the Italians whom he knew called him “that fucking Frenchman.” (Through the 1920s organized crime followed ethnic lines with separate enterprises for those of Italian, Irish, and Jewish backgrounds; by the 1950s, the Italians had murdered enough of rival ethnicities to take firm control.) This is subtly referenced later in an ironic scene where Deuce watches the classic 1971 “People Start Pollution, People Can Stop It” television commercial featuring a crying Indian played by Iron Eyes Cody – who, it turned out, falsely claimed to be of Native American Cherokee and Cree ancestry although he was actually a full-blooded Italian. That sort of confident directorial touch and attention to detail (and occasional Easter Egg) run throughout the film.

Director Tommy DeNucci told me “we’re not making a documentary,” and that’s an understatement. Some of his deviations from historical accuracy are very wise: it helps the story to relocate the site of the robbery from its real location on the northern edge of South Providence to the city’s nicer looking and more picturesque downtown, with establishing shots of the landmark Turk’s Head Building and its Westminster Street plaza. That’s understandable in part because the original vault no longer exists, but also because it was little more than a visually unappealing glorified storeroom. Instead, as a proxy the film takes us into the huge vault complex under 111 Westminster Street, the now-vacant Industrial National Bank that is commonly known as the “Superman Building,” a much more elaborate setting that for good reason looks exactly like what one imagines a bank vault to be.

Some of the fictionalized elements are quite funny in-jokes. In an early scene, Deuce and Chucky are robbing a store when Chucky accidentally fires his gun and hits someone in the leg; in reality, it was Deuce who was so incompetent with guns that Chucky had taken to putting blanks rather than live cartridges in Deuce’s gun. The film shows, after the robbery, wise guys in the parking lot all implausibly claiming to be coin collectors, but at least one of the boxes in the vault was rented by William and Mildred Lamphere, who really were coin dealers the IRS was chasing for hundreds of thousands of dollars. Events inside prison are moved from the Massachusetts State Prison in Walpole to the Adult Correctional Institution in Cranston. The film character Gerry Ouimette, played by Don Johnson, is a composite of Gerry and his brothers John and Walter for narrative simplicity. In the film, the robbers call each other “Buddy” to conceal their real names; in reality, they called each other “Harry” – and they reportedly got the code name idea from the heist film The Taking of Pelham 123 released a year before the robbery.

By far the most problematic aspect of the script, in my opinion, is the complete fictionalization of Karyne Sponheim, the girlfriend of Deuce, for some reason renamed “Karyn,” dropping the final “e” from her name. In the film, they meet when Deuce robs a store where she works in Providence, and he invites her home for a meal home-cooked by his mother; in reality, Karyne was an expensive prostitute Deuce picked up in Las Vegas. In the film, Karyn knows from the beginning that Deuce is a criminal and she picks him up in his car when he gets out of a stint in prison in RI; in reality Karyne didn’t even know Deuce’s real name because he was using the alias “Dennis Allen,” and not only did Deuce not have a car but never learned how to drive because he spent most of his adult life in prison.

In the film, Karyn is played by the extremely beautiful – and African American – Samira Wiley, making their interracial relationship notably progressive for the 1970s; in reality Karyne was regarded as extremely beautiful – but she was white. (Nor were these people racially progressive in their outlook. At the trial, according to The Last Good Heist, defendant Jacob Tarzian said to assistant prosecutor John Austin Murphy, “Jesus, Murphy. I was sorry to hear… I hope it isn’t true. Your sister’s married to a colored guy.” Murphy responded, “That’s right. You don’t have to feel sorry.” Murphy also said defendant Jerry Tillinghast whispered to him, “Hey, Murphy. How’s it feel to have those nigger kids running around your house?”) The cultural gulf between the real Karyne and Deuce was vast: at one point they had an argument because he wanted to celebrate a classic Christmas with a tree and so forth because he missed that for years in prison, and he became upset that she did not share his enthusiasm because she was Jewish.

The film only briefly hints at something else: in reality, the woman Deuce thought was his mother was his biological grandmother and the woman Deuce thought was his older sister was his biological mother, facts his family hid from him until adulthood, the discovery influencing his well-known distrust of women to the point of misogyny. In the film, Karyn and Deuce fall in love; in real life, there seem to have been honest feelings for each other, but he physically beat Karyne enough that she regularly had to use makeup to cover bruises on her face. In the film, she turns him in out of a desire to save his life; in reality, she had him arrested because he broke into her Las Vegas apartment and was lying in wait for her to return while she hid out at her mother’s. In the film, the epilogue says that Deuce and Karyn never saw each other again after she turned him in; in reality, Karyne testified against him at his trial before she was killed at age 30 as a pedestrian by a drunk driver.

I fully understand the need for literary license in telling a good story, and much of the fictional Karyn makes sense in that context, including the change of hometown, the change of profession, and even the change of race – but it crossed a line for me to erase completely the documented history of serious domestic violence; while Deuce was certainly a “bozo” inept in many of the basic skills of life, he was not, as director DeNucci described him, a “gentlemanly” bozo. Chucky was rumored to have murdered more than a few, but to what extent that was true or just image-making will never be known; in Massachusetts around Lowell, he was a small-time crime boss who controlled illegal gambling, extortion, and drug trafficking in his territory, being careful to stay far away from Rhode Island and Boston to avoid conflict with Patriarca.

And, despite my concerns about departure from the true history in a few cases, it is above all a good story well told.