As our world inches closer to nuclear war than it has in decades, we prepare to observe the anniversary of the Allied victory over Japan ending World War II, finally brought about by the first (and, so far, only) use of atomic weapons in combat.

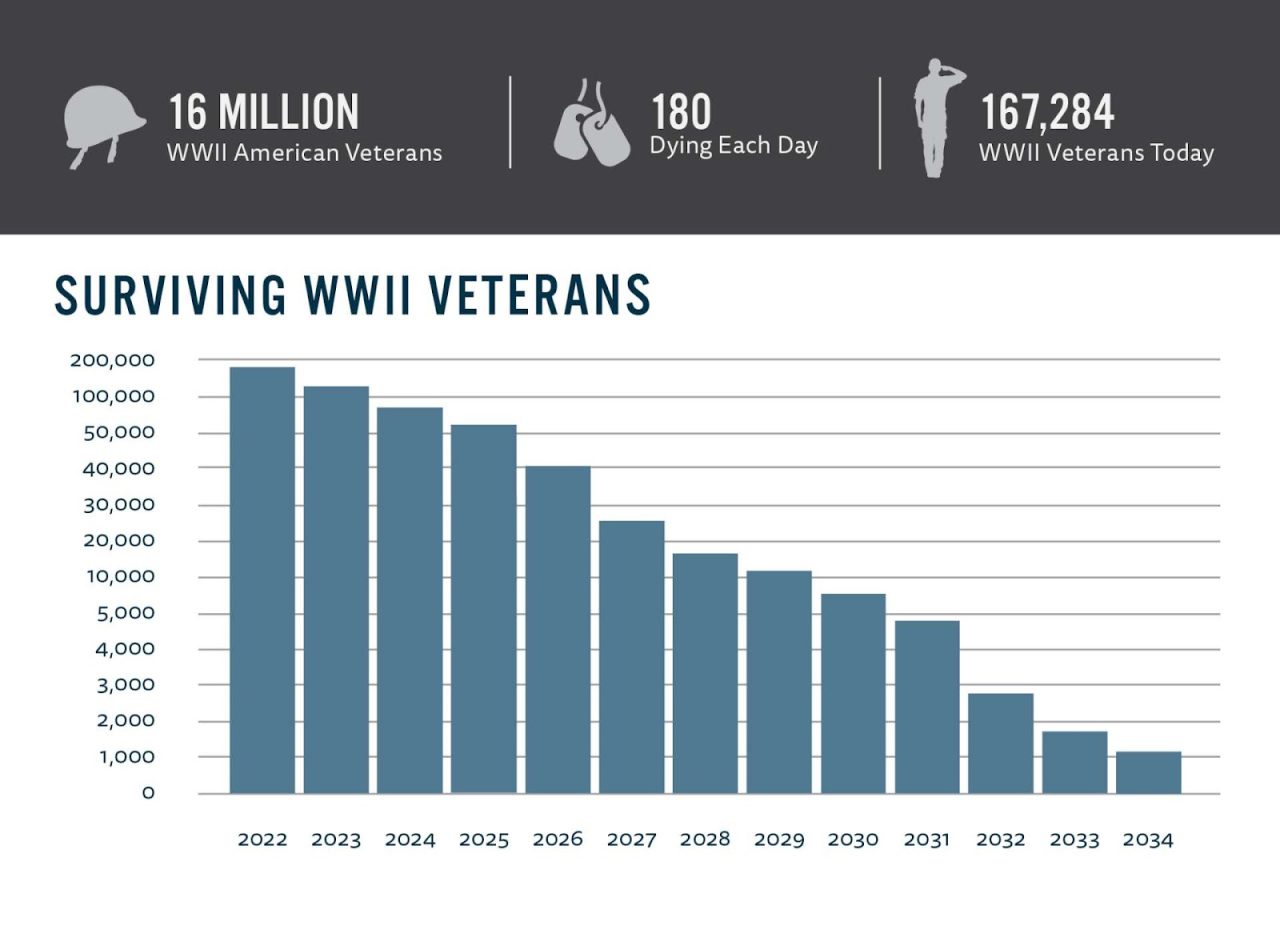

Rhode Island is the sole state where this once widely-recognized observance remains a holiday, Victory Day, legally enshrined (§25-3-1(5)) on the second Monday in August, one of only nine (like July 4th and Christmas) entitling employees to time-and-a-half pay. RI created the holiday in 1948, but as of 1975 every other state has taken it off their books. Despite repeated efforts to abolish it amidst allegations that it is a triumphalist celebration of the killing of several hundred thousand people, it survives as a state holiday due, it is generally understood, to its fortuitous position during the good weather of the summer in August and to an unwillingness to offend veterans of the war. In 2023, of the 16 million American veterans of World War II fewer than 160,000 survive, about 1,000 of them in RI, so the origins of the holiday are fading from living to historical memory.

It was clear to everyone that the war was coming to an end, and after the surrender of Germany on May 8, 1945, the conflict ceased in Europe leaving Japan the only member of the Axis still fighting. The Allied powers involved in the Pacific war (the United States, the United Kingdom, and China) on July 26 issued the Potsdam Declaration, an ultimatum demanding the unconditional surrender of Japan and threatening “prompt and utter destruction.” Ten days earlier on July 16, a secret test was carried out in New Mexico successfully proving the new American atomic bomb worked.

(Photo: Army Signal Corps Collection in the U.S. National Archives via Wikimedia Commons.)

Although running out of everything from food and fuel to soldiers, on July 29 Japan communicated its rejection of the Potsdam Declaration and an intention to continue the war. That led to decisions by the United States to use an atomic bomb on the city of Hiroshima on August 6 and on the city of Nagasaki on August 9. At the same time, unaware of the secret agreement by Russia at the Yalta Conference in February to declare war, desperate Japanese hopes for diplomatic intervention by the still-neutral Soviet Union were dashed by the invasion of Manchuria. The Empire of Japan began the process of surrendering, finally broadcasting a radio message to the Japanese people by the emperor at noon on August 15 that has come to be regarded historically as the moment ending the war.

The current controversy about the appropriateness of continuing to observe a holiday is motivated almost entirely by the moral questions raised by the atomic bombings. For many years, it was accepted that without them the war would have dragged on for at least another year with concomitant loss of life greater than from the bombs, but that came to be disputed by some historians. The effect of the bombs on convincing Japan to surrender has also been disputed, but Emperor Hirohito himself cited them in his radio address, noting “the war situation has developed not necessarily to Japan’s advantage” and explicitly saying, “Moreover, the enemy has begun to employ a new and most cruel bomb, the power of which to do damage is, indeed, incalculable, taking the toll of many innocent lives. Should we continue to fight, not only would it result in an ultimate collapse and obliteration of the Japanese nation, but also it would lead to the total extinction of human civilization.”

Evan Thomas published The Road to Surrender in May and he summarized the criticism: “In more recent years, scholars of World War II have argued that it was not necessary to drop the atomic bombs on Japan, or that it was not necessary to drop more than one, or that the Japanese might have been moved to surrender if the United States had staged a demonstration of the bomb’s power on a deserted island. That argument has gained popular currency.… In school and college, many had been exposed to books and scholarship that argued that, by August 1945, Japan was ready to surrender, and that America’s real motivation in dropping the A-bomb was to intimidate Russia in the earliest days of the Cold War.”

But, he continues, “The facts are otherwise. On the morning of August 9, 1945, after the United States dropped two atomic bombs and Russia declared war on Japan, the Supreme Council for the Direction of the War, the group of six leaders who ran Japan, deadlocked on whether to surrender. The vote was a tie, three to three. The most powerful leaders, the ones who ran the army, wanted to keep on fighting. For five more days, Japan teetered on the edge of a coup d’état by the military that would have plunged Japan into chaos and extended the war for many bloody months.… The problem for [the Allied leaders] — the looming, intractable, seemingly unsurpassable obstacle — was that Japan was unwilling to surrender. By the summer of 1945, the empire appeared to be defeated. Japan’s ships had been sunk, its cities burned, and its people were on the verge of starvation. But its military leaders, who commanded 5 million soldiers under arms, as well as greater citizen armies equipped with pitchforks and scythes, seemed bent on mass suicide. To attempt to defeat them by invading and seizing territory seemed sure to produce the greatest bloodbath of all time — and the Japanese, or at least their military leaders, beckoned the Americans to it.”

After the deeds were done, doubts quickly emerged. Thomas writes, “In November 1945 J. Robert Oppenheimer, the chief scientist in charge of developing the bomb at the secret laboratories of Los Alamos, appeared in the Oval Office and cried out to President Truman, “’Mr. President, I feel I have blood on my hands!’” Truman said later that he called Oppenheimer a “cry-baby” and responded, “I told him the blood was on my hands – to let me worry about that.” Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson suffered a minor heart attack when he brought Truman photos of Hiroshima and a major heart attack a month later when he brought the first plans for the control of atomic weapons.

The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, which devotes its July issue to Oppenheimer, in January set its symbolic “Doomsday Clock” that measures the notional time to the end of the world through human action at 90 seconds to midnight, as close as it has ever been in its 75 years of existence. Oppenheimer is being brought back into public prominence by a new Hollywood blockbuster movie released on July 21, based on the 2005 book American Prometheus by Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin, their title inspired by the ancient legend: “Like that rebellious Greek god Prometheus – who stole fire from Zeus and bestowed it upon humankind, Oppenheimer gave us atomic fire. But then, when he tried to control it, when he sought to make us aware of its terrible dangers, the powers-that-be, like Zeus, rose up in anger to punish him.”

For the first time in decades, the invasion of Ukraine by Russia and the ruthlessness of Russian President Vladimir Putin has political and military leaders talking about the possible use of nuclear weapons in combat. US National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan was quoted a few days ago by Robbie Gramer in Foreign Policy: “I think that there are two caricatures in the discourse about the threat of the use of tactical nuclear weapons. One caricature is the Biden administration is paralyzed by the nuclear threat and therefore won’t support Ukraine sufficiently. I think that is nonsense. The other caricature is this nuclear threat is complete nonsense. ‘Don’t worry about it at all. It’s to be completely discounted.’ That also is wrong. It is a threat. It is a real threat. It’s one we need to take seriously. And it is one that does evolve with changing conditions on the battlefield.”

A few years ago, I witnessed an exchange as a Providence club was closing at 2:00am, open an extra hour because of the Victory Day holiday. The DJ was of Japanese ancestry (as his stage name emphasized) and, after stopping the music, delivered a political tirade about how evil the US had been to drop those atomic bombs. A close friend of mine, a patron on the dance floor, loudly challenged that version of history and shouted, “Take your garbage remarks to China and see what they think.” This was a reference not only to the current communist government of China that is unfriendly to free speech, but also to the grave mistreatment by Imperial Japan of its Asian neighbors, including China and Korea. The DJ seemed shocked that anyone could disagree with him. The exchange stayed purely verbal but it is easy to imagine that ranks might have formed up on each side because of the strongly opposing views, proof of William Faulkner’s observation, “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.” People deeply care about this.

Thomas explained in an interview with Terry Gross on Fresh Air that the Japanese knew they were defeated but, “They believed that if they could make the Americans bleed enough, suffer enough, take enough casualties, then the Americans would give them terms that they wanted.” War is hell, and we forget that at our peril. No one knew what the atomic bombs would do in practice, and its creators were surprised that about half of the deaths happened weeks after the explosions, as they had neither contemplated nor understood the consequences of radiation or psychology. Only in August 1946, a year after the bombings, did Americans begin to understand their effects when The New Yorker devoted an entire issue to a book-length report from John Hersey in Hiroshima.

It is difficult to understand the mindset of the American people in 1945: the war started in September 1939 with the joint invasion of Poland from the west by Germany and from the east by Russia, but America remained neutral until the Japanese surprise attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941. It is estimated that between 70 and 85 million people died in connection with the war (including the Nazi Holocaust), about 3% of the pre-war population of the planet at the time. Japan lost 2.5 – 3.1 million, about 4% of its population. The United States lost 420,000, about 0.32% of its population. Although America came through relatively unscathed in comparison, the years of privation and uncertainty took a toll, especially as no one knew which of their family, friends, and neighbors would be among those hundreds of thousands killed. The Providence Journal estimated that 50,000 people filled the streets of Providence in a spontaneous celebration on the day of the Japanese surrender.

Japan today is a prosperous democracy, committed to the cause of peace, and thoroughly abjures its militaristic past. Japan holds a solemn commemorative ceremony every year on the date of the surrender, the National Memorial Service for War Dead (officially “the day for mourning of war dead and praying for peace”). They are not spending the day grilling hamburgers and hot dogs, but their different circumstances demand different observance.

Is our celebration of the end of the war morally wrong? Were the atomic bombings the wrong decision? After substantial examination of the historical evidence, I believe both questions should be answered in the negative. There were no good options, only options that ranged from bad to worse. We must judge the people of 1945 according to what they knew and could have known.

In the modern world, we must make every effort to avoid the use of nuclear weapons, especially because their enormously increased power makes possible not merely the destruction of a city but the destruction of a continent. Accomplishing this requires an honest appreciation of history.