When talking about American bar culture, one cannot separate the intrinsic cultural influence of individuals of color. What are considered classic cocktails have deep roots in African American communities, dating back to post-slavery and the subsequent Great Migration. The communities formed in larger northern cities became epicenters of culture, where libations flowed freely until the onset of Prohibition. During Reconstruction, and following the Civil War, African American communities strove for civic participation and political equality. By 1875, sixteen African American congressmen represented their communities. Unfortunately, a brutal campaign of racial terrorism aimed at re-establishing white supremacy in the Democratic South, coupled with the introduction of Jim Crow laws, stripped these newly freed communities of their representation and ushered in an era of segregation.

Despite ongoing racial pushback, these communities created spaces to come together. Writers, intellectuals, and musicians found refuge and camaraderie in neighborhoods like Harlem and Pullman, Chicago while enjoying culturally creative libations — though Prohibition loomed on the horizon. Many African Americans worked in hospitality, particularly in renowned venues like the Savoy Ballroom and The Cotton Club. Change, however, is often fueled by curiosity. The elite of New York’s fascination with jazz and swing culture drove revenue both before and during Prohibition. Cocktail culture itself began in dark, cozy private clubs during the early 1900s.

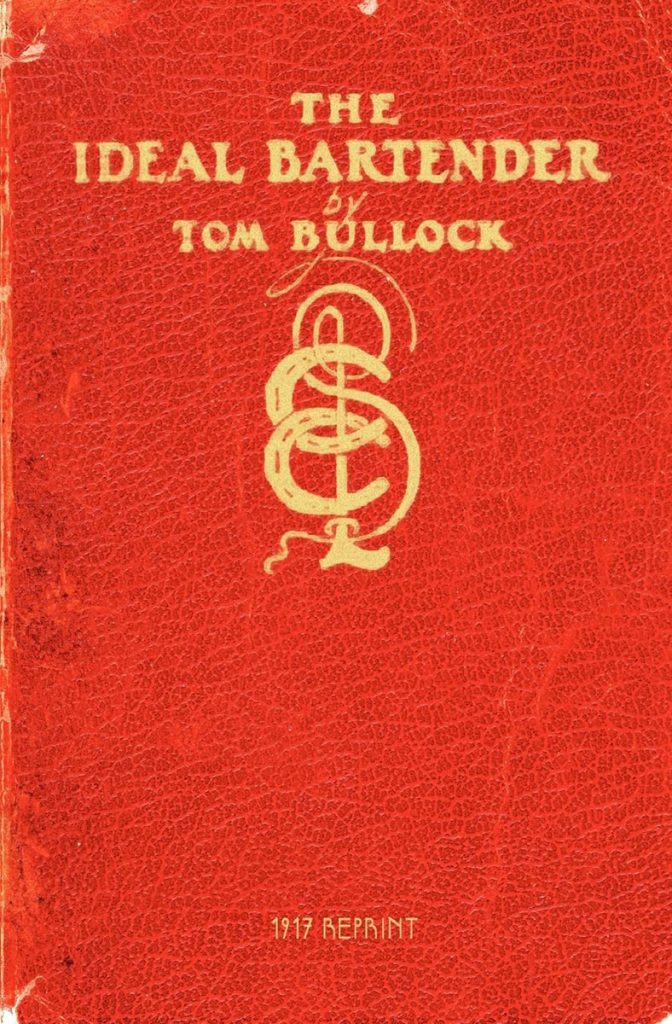

As Tom Bullock famously wrote in the dedication to his cocktail book, The Ideal Bartender, “To those who enjoy snug club rooms, that they may learn the art of preparing for themselves what is good. Is it any wonder that mankind stands open-mouthed before the bartender, considering the mysteries and marvels of an art that borders on magic?” These words remain as true today as they were then. The Ideal Bartender is credited as the last cocktail book published before Prohibition. Tom Bullock, a trailblazing African American bartender, worked at notable establishments such as the Pendennis Club, the Kenton Club, a railway car bar, and most famously, the St. Louis Country Club.

Below are two un-familiar favorites penned by Tom and, edited for modern application:

BLITZ ROYAL RICKEY

½ Lime or Lemon

4 dashes Raspberry

1 pony(ounce) Vermouth

¾ jigger Gin (1.5 ounce jigger)

Fill with imported ginger ale and stir, dress with fruit and serve.

PINEAPPLE JULEP (for 6 in a punch bowl)

1 Quart Sparkling Moselle (Sparkling Riesling, a forgotten classic)

1 Jigger (1.5 oz) Cusenier Grenadine

I Jigger (1.5 oz) Maraschino (liquor)

1 Jigger (1.5 oz) Sir Robert Burnetts Old Tom Gin

1 Jigger (1.5 oz) Lemon Juice 1 Jigger (1.5 oz) Orange Bitters

1 Jigger (1.5 oz) Angostura Bitters

4 Oranges Sliced

2 Lemons Sliced

1 Ripe Pineapple, Sliced and Quartered

4 Tablespoons of Sugar

1 Bottle Apollinaris Water (Sparkling Mineral Water)

Add a large square of ice to the bowl; dress with fruits and serve julep in fancy stem glass.

The Ideal Bartender is available free through project Gutenberg. Tom is only one piece of the tapestry of modern bar culture, for more information check out:

The Blacker the Berry: A Cocktail Recipe Book by Niki l. Brown

Black Mixcellence: A Comprehensive Guide to Black Mixology By Tamika Hall •