When Elizabeth Rush arrived in Yangon, Myanmar, in 2008, she dwelled on the former capital’s colonial buildings. For nearly a century, the British Empire claimed and governed the city as Rangoon and its greater territory as British Burma. The independent union, federating more than 100 distinct ethnic groups and languages into seven states, fell with a coup in 1962 when a military junta established a dictatorship. For decades, nonviolent resistance and armed movements flared across the country, often suppressed. In Yangon, homes were collectivized and reassigned. “Slowly being eaten away by dampness and mold,” Rush wrote later in an essay for the Cook’s Cook, she saw their faded exteriors as “a poem in architecture.”

Browsing one of the Myanmar’s English-language newspapers, Rush paused over an article noting plans for the auction of state-owned assets, including residential properties in Yangon. Commitments to economic liberalization had followed years of unpredictability. The government relocated the capital 200 miles inland to Naypyidaw, a new, purpose-built city, and cracked down on nonviolent demonstrations against economic malaise, protests branded the Saffron Revolution. Then, in May 2008, Cyclone Nargis devastated the country. Nearly 85,000 people were killed and more than 50,000 went missing, raising the estimated death toll to 135,000, according to official figures cited by the International Federation of the Red Cross. The delta region at the mouth of the Irrawaddy River, most at risk from rising sea levels, bore the brunt of the storm.

On her walks in Yangon, Rush saw reminders of the infrastructure battered and destroyed by the storm, buildings reduced to rubble and roofing stripped clear of walls left standing. The sight of a young woman from the Irrawaddy delta finding refuge with her parents in the shell of an old theater left an imprint. For those whose residences remained intact, Rush couldn’t shake the realization that the planned auctions meant many of their homes were not only for resale, but also earmarked for demolition.

“You would have someone who sold soda on the corner living alongside a lawyer living alongside a teacher,” said Rush in an interview after moving into a new house in Providence, her first as a homeowner. “All those people are going to be displaced, and it’s going to be this really massive transformation.”

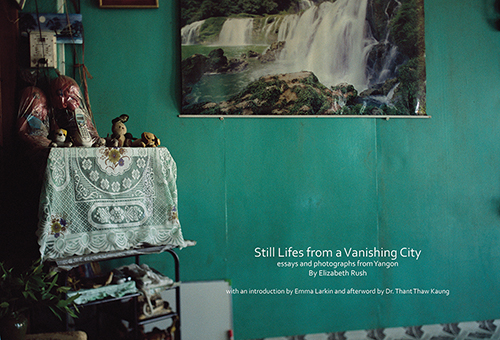

Rush returned to Hanoi, Vietnam, where she worked for a contemporary art gallery, and contacted Albert Wen, publisher of ThingsAsian Press, whom she had met at a work lunch. Wen asked if Rush had ideas for a book on Myanmar, and she proposed a collection of essays and photographs about the people being uprooted by the forthcoming auctions in Yangon. Wen accepted, offering an advance to assist with the project. For the next two years, Rush traveled back and forth to Yangon, at first from Hanoi and later from New York, for four weeks at a time, the maximum stay allowed on a tourist visa. A source in Yangon provided Rush with a list of addresses up for auction, and she went door to door with a Burmese translator. Having studied photography in high school and college, she captured snapshots with her Canon F-1 camera to pair with her writing.

In Granta, a literary magazine based in London, Rush described the undertaking as “an archive of sorts, an assemblage of the rich, full lives people built in the wreckage of an abandoned empire.” Her photographs revealed private scenes of coal sacks stacked in a kitchen, a nativity scene tacked onto a wall above a fish tank, generations of family portraits, an empty clothes line with orange plastic hangers bunched together on a rope, and other glimpses into constructions of life within the spaces each resident called home, certain to be lost even if not yet gone. Posed and poised against cracked walls, collapsed roofs, and pulverized brick were residents, both individuals and families, revealing a sense of comfort, knowledge, and pride in their place.

“What home was and what they wanted to maintain, through this big change — ” Rush said, seated in an armchair beside unpacked moving boxes in her new living room. “In some ways, that’s the question really at the heart of Rising also.”

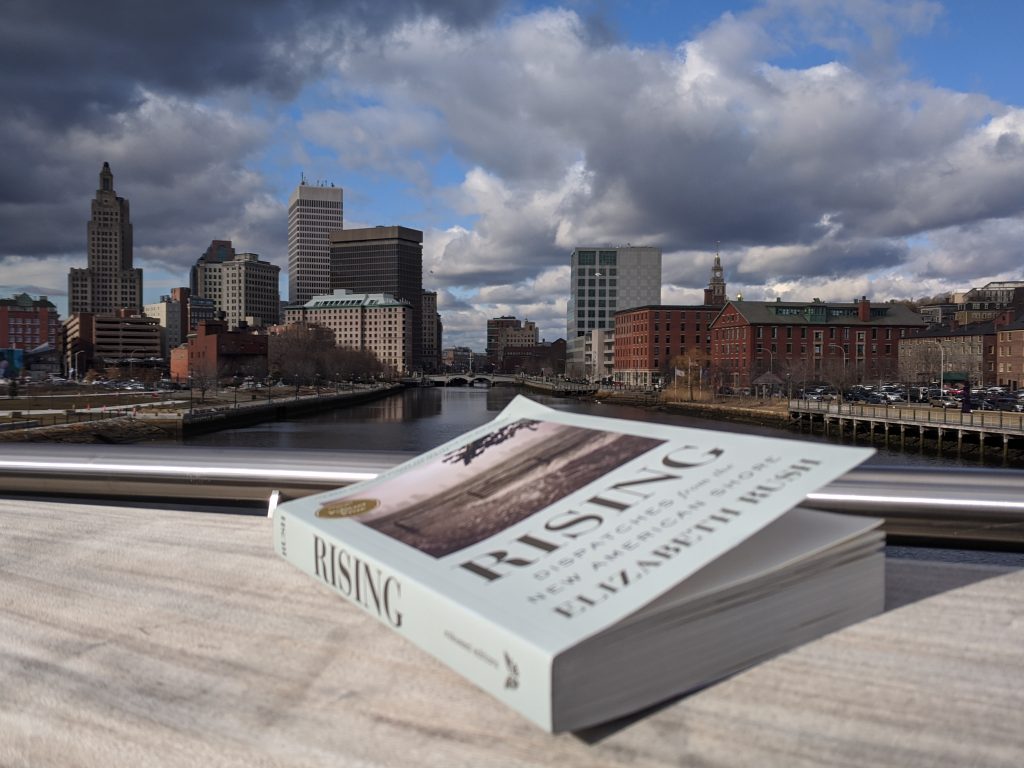

Far from Myanmar, Rush’s Rising: Dispatches from the New American Shore, the 2020 Reading Across Rhode Island one-state, one-book selection, surfaces the stories of coastal communities across the United States. She pens a requiem for the tupelo trees desiccated by increased salinity in Warren, Rhode Island, and travels to the disappearing bayous of Louisiana. She relives the wake of Hurricane Sandy on Staten Island and excavates the natural and built landscapes around one-time wetlands on the cusp of Silicon Valley and the San Francisco Bay. Rush’s reportage stitches science throughout vignettes and first-hand narratives to frame sea level rise within the contours of her home country, yet with an acute sense of how each individual account is but a brush stroke in the impressionism of a global reality.

“How I wrote Rising was very deliberate,” said Rush. “It doesn’t engage directly with climate-change politics because I wanted to write a book that would have a very wide door for people to walk into.”

“I was worried it would be a dull, didactic book on climate change, but I was hooked at chapter one,” said Kate Lentz, executive director of the Rhode Island Center for the Book, the nonprofit that manages the Reading Across Rhode Island program. “I ended up finishing the book in two days.”

Growing up in Beverly, Massachusetts, a waterside suburb north of Boston, Rush went to local beaches and visited the salt marshes of Plum Island on day-trips. In high school, she thought about the social dynamics of public and private beach access. Moving to Portland, Oregon, to study at Reed College, she traded the coast for the mountains around the Willamette Valley.

“I knew that I actually wanted to be an environmental writer,” said Rush. “But I also knew that, like, half of the state of Oregon also wanted to be an environmental writer.”

Graduating with a bachelor’s degree in English, Rush integrated her interests in literature, art, nature and travel. After waiting tables at a local restaurant, she packed a waterproof bag with clothing, notebooks and cycling gear for a solitary trek from Seattle to Alaska.

“I wanted to tackle another challenge, which at the time was learning to be lonely, learning to be alone,” she said.

Biking alongside the wilderness of Vancouver Island and ferrying her way through the straits, fjords and coves of British Columbia, after roughly 2,000 miles and more than two months, Rush reached Skagway, north of Juneau in the Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park.

Following her spell of solitude, Rush found work with Art Vietnam in Hanoi, writing marketing and editorial copy as the gallery hosted exhibitions critiquing colonialism, reflecting on exile and confronting nostalgia for lost childhood during a period of loosening artistic censorship. While Rush worked in Hanoi and traveled back and forth to Yangon for her book project, she enrolled in a Master of Fine Arts program at Southern New Hampshire University designed for remote students. Because her mother worked for the school, Rush received discounted tuition and was able to pursue her master’s degree without incurring debt. Rush moved from Hanoi to Brooklyn, and for two years visited campus in Manchester, NH, for two one-week stints each year.

While working on her MFA in nonfiction, developing her Myanmar project and ghost-writing somebody else’s memoir, Rush edited H is for Hanoi, I is for Indonesia, and M is for Myanmar, language-learning books for children illustrated by Nguyen Nghia Cuong, EddiE haRA, Khin Maung Myint respectively, and wrote articles as a freelancer. A reporting trip to Myanmar’s neighbor Bangladesh left her with an unshakeable realization of the significance of wetlands.

“At first, I was like, wow, those are boring,” said Rush. “I became way more fond of them.”

For Le Monde diplomatique, a Paris-based monthly, Rush covered India’s efforts to construct a fence along 2,000 miles of its border with Bangladesh. The reality was hazier, Rush found, as people and goods adapted around the structure as it was built. Water, she noticed, was one overlooked problem in the lives of residents on both sides of the border. A history of irrigation upstream and rising sea levels downstream conspired to turn a fertile region into one of failing crops in less than a decade. She started to view shorelines as kinds of borders, an idea that conjures promises of control, but in practice is defined by constant, malleable relationships.

“I was reluctant to play into one of the earliest climate change clichés, that of a drowning Bangladesh,” she wrote in Rising, about meeting a young man considering migrating to India as he struggled with a wilting patch of mustard greens in soil tinged with salt. “Instead I tucked the knowledge away and returned to the United States. But I was changed, haunted.”

“I became really interested in how wetlands are these liminal spaces that inherently change,” she said. “I started to realize that I had to write about wetlands to write a sea level rise book.”

When Rush returned to New York, she began to research the science of climate change, including glacial melt and sea level rise. In addition to writing essays on Myanmar, she turned to environmental reporting. A story for the Global Oneness Project brought her to Louisiana, and after Hurricane Sandy, she covered the storm’s impact on communities on Staten Island for Urban Omnibus and Al Jazeera. Rush taught writing courses as an adjunct professor at the College of Staten Island and international reporting at CUNY’s Graduate Center for Journalism.

In March 2015, ThingsAsian Press published Still Lifes From a Vanishing City: Essays and Photographs from Yangon, Myanmar. Art Vietnam, Rush’s former gallery in Hanoi, planned an exhibition of her photography. That summer, Rush moved from Brooklyn to Providence, when her now-husband Felipe Martínez-Pinzón accepted a position at Brown University as an assistant professor of Hispanic studies with a specialty in 19th-century literature. During Rush’s and Martínez-Pinzón’s first weekend in Rhode Island, they cycled to the state’s East Bay along a former railway bed repurposed into a bike path.

The peninsula holding Warren and Bristol forms a teardrop of land falling into the Narragansett Bay. Its earth is pocked with coaly shale and sandstone, with granite further south. Along the towns’ border lie two protected wetland sites. On the Bristol side of the line, the Audubon Society of Rhode Island manages a wildlife refuge, nature center and aquarium. In Warren, Jacob’s Point is protected land forged from private property granted between 1987 and 1994. Michael Gerhardt, president of the Warren Land Conservation Trust, called Jacob’s Point “one of the prettiest places in Rhode Island.” Rush found herself returning to the salt marsh regularly throughout the summer, photographing osprey and observing dead tupelos.

“I have come to think of the large leafless trees lining our marshlands as canaries in one giant coalmine,” Rush wrote in The Providence Journal after her visits. “Just above Jacob’s Point sit a handful of very fine homes indeed, which, whether they know it or not, are reliant upon the health of the wetland at their door steps.”

“When we talk about a 100-year storm, we’re not talking about 100 years,” said Gerhardt of the land trust. “We’re talking about a 1% chance of it happening in any given year.”

With the start of the 2015 school year, Rush left Providence to commute 200 miles back and forth to Lewiston, Maine, each week. Recipient of the Andrew Mellon Postdoctoral Fellowship for Innovative Pedagogy at Bates College, Rush taught nonfiction writing and revisited several of her past essays and articles, including her op-ed on Jacob’s Point. With interjections of memoir, she adapted and expanded her work into a collection of narratives around sea level rise.

In November 2016, Milkweed Editions, an independent nonprofit press based in Minneapolis, acquired the rights to the manuscript, then titled Rising: Essays from the Disappearing American Shores. The following year, Rush completed her fellowship at Bates, she and Martínez-Pinzón celebrated their wedding, and they settled together in Providence full-time as Rush began a visiting lectureship in the English department at Brown University.

Days before Rising: Dispatches from the New American Shore published in June 2018, Boston’s mayor Marty Walsh hosted the International Mayors Climate Summit at Boston University, seeking to connect the leadership of cities around the world on climate-related issues. Days later, Providence College and Salve Regina University joined the Sisters of Mercy, a religious order in Cumberland, and Saint Mary Academy – Bay View, a girls school in East Providence, to call for climate action alongside more than 500 signatories to the US Catholic Climate Declaration. At the same time, Rhode Island’s Coastal Resources Management Council introduced an online modeling tool to predict sea level rise and storm surges in communities across the state, designed to aid local governments and organizations with their planning.

Reviews celebrated Rush’s lens into changed and changing environments. In her publisher’s hometown of Minneapolis, The Star Tribune called Rising “a lovely and thoughtful book, so lyrical that you forget how much science it delivers.” In Rush’s new home, The Providence Journal noted “an exacting poetic certitude” while “picturing the current and future maelstrom of misery, dislocation, privation and suffering that even nominal sea rise will bring in the coming decades.” In The New York Times, David Biello, science curator at TED, wrote: “This is a book about language, first and foremost, a literary approach to a real-world problem.” Publishers Weekly gave a starred review, concluding: “In the midst of a highly politicized debate on climate change and how to deal with its far-reaching effects, this book deserves to be read by all.”

“It’s like learning to check my discourse at the door and listen,” said Rush about her approach to both her research and writing. “Then, invite the reader into that experience of listening.”

Rush was in Bogotá, Colombia, with Martínez-Pinzón when she missed several calls from her editor. Rising had been named a finalist for the 2019 Pulitzer Prize in general nonfiction, in company with Bernice Yeung’s In a Day’s Work revealing the sexual harassment and violence faced by female farm laborers, care providers and janitorial workers and Eliza Griswold’s Amity and Prosperity honing in on the effects of fracking in a Pennsylvania community. Online, the Pulitzer Prize featured Milkweed’s description: “Rising is both a highly original work of lyric reportage and a haunting meditation on how to let go of the places we love.”

In December 2019, the Rhode Island Center for the Book announced the Pulitzer Prize finalist had been selected as the nonprofit organization’s 2020 Reading Across Rhode Island pick. Started as a civic-engagement effort in the wake of September 11, 2011, the program was designed to bring communities across the Ocean State together through deep and sustained discussions of a single book during each calendar year. Past selections included What the Eyes Don’t See by Dr. Mona Hanna-Attisha, The Hate U Give by Angie Thomas, and Just Mercy by Bryan Stevenson. For Rising, the Rhode Island Center for the Book published a curriculum for educators and a resource guide to aid librarians, booksellers, book groups and other readers.

“We are really lucky to have a local author who has gifted us such lyrical prose and included the Rhode Island landscape in the narrative,” said Lentz.

In January 2020, Governor Gina M. Raimondo signed an executive order titled, “Advancing a 100% renewable energy future for Rhode Island by 2030,” in which she directed the Rhode Island Office of Energy Resources to deliver a plan by year-end mapping out initiatives to advance a renewable future for the state within the next decade, with initial steps in 2021.

“Yes, it’s great,” said Rush. “We should make our energy renewable. We also need to think about how you do a sliding scale and how do you help lower-income families pay for that?”

The U.S. Energy Information Administration ranked Rhode Island 46th out of all 50 states and Washington, DC, for average electricity costs in 2018. At a rate of 20.55 cents per kilowatt-hour, Rhode Island is 114% higher than Louisiana, the state with the lowest rate at 9.59 cents per kilowatt-hour. As a result, households in Rhode Island have the sixth lowest average monthly consumption of electricity in the country, yet remain in the middle of state rankings with the 25th highest monthly bills. Rhode Island households spent an average of more than $1,450 per year on electricity.

“We also have to look at why it’s so expensive and how can we maintain affordability for all residents,” said Rush.

“I feel both absolutely thrilled and excited that I can be part of a more local conversation about what climate change means in the present tense and how our growing awareness of it can help us advocate for real policy change,” she said.

An essential step, said Rush, is documentation. Compiling Still Lifes From a Vanishing City was a matter of preserving, not preventing, the auctioning and demolition of homes in Yangon. She may have written Rising as an open door into the human impact of rising sea levels, on the one hand localized and on the other unconstrained, but the questions of where, when, how, and whether policymakers themselves rise to action remain to be seen.

In Rush’s next book, The Mother of All Things, planned for publication in August 2022, again with Milkweed Editions, she seeks the center of the story, detailing a singular journey — hers, on an expedition with the National Science Foundation to the calving edge of the Thwaites Glacier, seeking to understand the ice shelf’s rapid melt as it births new icebergs. Entwined with her travels to Antarctica is her journey with pregnancy, as she anticipates an upcoming due date.

“This past year has been a miracle,” said Rush.

“I’m just really excited for it to be a springboard for a year of — or the beginning of a lifetime of — seeing real change around climate change in Rhode Island.”