In 1974, the Navy declared three parcels of Rhode Island land as excess to their needs, including the air base in Charlestown. The Naval Auxiliary Air Station Charlestown was developed in 1942 as a WWII-era military asset, training historical figures like former president George Herbert Walker Bush. When the base was disestablished in the early ‘70s, what ensued over the next several years was a heated debate between state government, local companies, organizations, and concerned citizens about how to use the land.

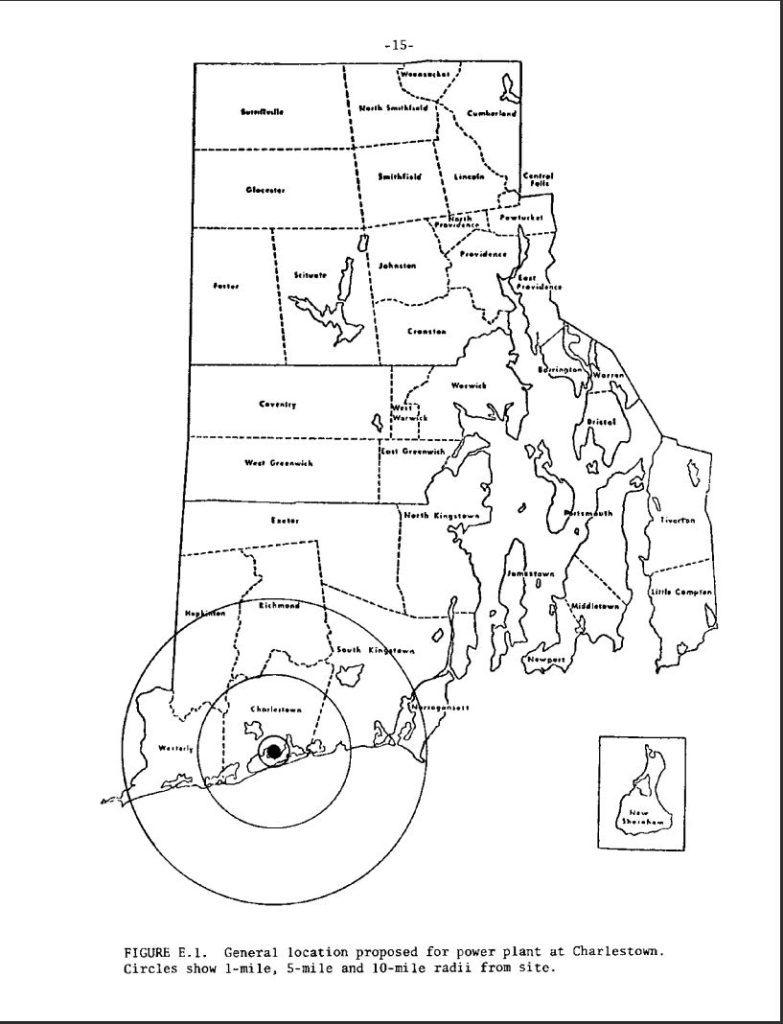

One company vying for control of the land was New England Electric System (NEES), who proposed using the land to build the first nuclear power plant in Rhode Island. Many opposed the construction of a nuclear power plant out of ecological conservation concerns, including Edwin Foster Drew (nicknamed “Frosty”), who led a coalition to fight the plant proposal.

As a child, Frosty contracted Polio, a year before the vaccine was created. The virus resulted in life-long physical ailments for Frosty; however, despite these health challenges, he went on to graduate from Brown University, pursuing interests in writing, ecology, and land use. In his adult life, he was the president of the RI Chapter of the American Littoral Society and chairman of Rhode Island’s Commission of Energy. Unfortunately, health complications led to his untimely death in 1976, at the age of 28, during the fight over the land use.

Three years later, after years of contentious debate within the Charlestown community, the land was deeded to Ninigret Park and National Wildlife Refuge. There would be no power plant, at least not on this plot of land. The building that had formerly housed the Chief Petty Officer’s residence on the naval base was repurposed as a nature center and named in memory of Frosty Drew. His efforts to preserve and appreciate the natural world were memorialized when the Frosty Drew Nature Center opened in 1983, later adding the observatory in 1988.

The air that had previously been used to train Hellcats and Avengers pilots, their planes slicing through the sky with military precision, now stood still, but for the golden eagle, the ruby-throated hummingbirds, migratory geese and waterfowl. In addition to admiring what was around them on Earth, people looked up through the observatory’s equipment, taking in celestial bodies beyond the naked eye. They saw the subtle, luminescent bands of Saturn. They could marvel at the oddity of deep space objects like Witch’s Head, a nebula that resembles the profile of a screaming (or laughing, perhaps) sorceress.

Today, the Frosty Drew Observatory boasts an extensive life list seen through their telescopes. There is as much to see in the sky as there is in the lush wildlife refuge that houses the observatory. Nearby, New England cottontails hop through tall grass, grazing. Swamp rose flowers along the bank. Sycamores and Red Maples sway in their silent magnitude. It could have gone so differently, and yet, the stars blink on.

Frosty Drew Observatory is open to the public on Fridays, weather permitting. Learn more at frostydrew.org.

MORE TO EXPLORE:

Ladd Observatory: 210 Doyle Ave, Providence, open to the public Tuesday nights. brown.edu/Departments/Physics/Ladd

Seagrave Memorial Observatory: 47 Peeptoad Rd, North Scituate, open to the public Saturday nights. theskyscrapers.org

Maragaret M. Jacoby Observatory: 400 East Ave, Warwick, open to the public Wednesday nights. ccri.edu/physandengr/physics/observatory