Leroy doesn’t have gloves. To protect his fingers from the cold – which is pretty intense today – he keeps his parka pulled down over his hands; it makes holding his cardboard sign difficult, and he shifts it several times during the time we spend, talking and watching cars go by, but he never complains. Complaining is one thing I didn’t hear from any of the flyers I interviewed.

“Flyers,” is what they call themselves – and when they’re working a corner, they call it “flying” – derived from the phrase, “flying a sign.” The practice has become more common in recent times of economic hardship, and received more public attention when recent ordinances were proposed in Providence, Cranston and Warwick to prevent people from either handing out or receiving fliers or money from the street or from medians.

Leroy was working the service road parallel to 95 on the West Side. Although that’s right in front of Crossroads, he actually overnights at Harrington Hall and has been a flyer for two years. Chester is an immigrant from Liberia. Complications around his green card (which is now properly up to date) led him to unemployment. He’s now looking for janitorial employment, and filling his time flying in between trips to the library’s job search resources section. Nate, who likes to work North Main St, used to get work “beating people up. Somebody would hire me for that, and I

was really good at fighting, so I’d do it. But then my freedom was at stake – the judge told me, if he saw me in court again, he’d send me away for 25 years. So I had to turn my life around. This is where I start, but I’m looking for work — any kind of legal work.”

I interviewed a half dozen flyers for this story. One refused to speak to me – here’s some of what the others told me.

How much do you make out here?

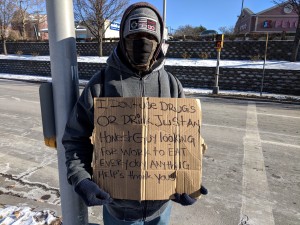

There was a lot of reluctance to answer this question, but the consensus seemed to be around $5/$6 an hour. I made $4 in my first hour; Megan Smith (an advocacy worker, see below) told us she made $2 and a granola bar on her best hour. She’s practiced a few times, but often her goal is to see if she’ll be harassed or get in legal trouble, not to optimize her profits). I questioned the math of one flyer who claimed he made $25/hr; in the half hour I was talking to him, he pulled in $2, but I may have been disrupting his flow. “Sometimes somebody rolls along, and you’ll get $20 from one person, and then you’re doing great, it changes everything,” said Chester. “Sometimes, you get some strange stuff too,” says Nate. “Yesterday, somebody gave me a full pizza. Not long ago, there was a woman who came three days in a row. She gave me sweatpants and socks and one time several shopping bags with whole chickens and rolls and soup and all kinds of food. That was more than I could eat, so I went around giving it to other people I knew were hungry,” he says. Nate is the only person I talked to who really seemed prepared for the weather, complete with a face shield. “Does that really help keep you warm?” I ask. “It’s not about that,” he answers. “There’s a lot of dust and exhaust out here. This helps me breathe in less of it.”

What do you do with the money you get? Is there something you save up for?

“Pancakes!” says Leroy with a slow, gentle smile, “I get pancakes at McDonald’s when I can. And transportation – getting across town.” Like most of the men I spoke with, Leroy is so soft spoken it’s difficult to hear him above the passing traffic.

Coffee was the primary purchase of another man who declined to share his name. “You don’t need that, but thank you for asking,” he said, of his name.

Nate says he uses the income mostly for clothes. At one point, a motorist stopped to talk to him for a while, and then offered him a job for the next day, when he’d come pick Nate up. Nate took what he’d saved for this occasion to get a new jacket and boots, to be presentable at the new job. The motorist never came back. “I also get food, and some cigarettes,” he admits, “but mostly I’ll do anything that might help me get a job.”

For Chester, who sleeps at Crossroads in Providence, the answer is also, “Food.”

Do people give you a hard time?

Everyone I spoke with agreed that hecklers are pretty rare. Drivers will mostly ignore the flyers, but will rarely be mean. Worst case, once in a while they’ll be flipped the bird. They also try to work during the day, so drunken shenanigans are at a minimum. “I’m not sure how long I work, but when it gets dark, I know it’s time to call it a day,” says Chester, a sentiment echoed by every flyer I spoke with.

What’s the hardest part of doing this?

Leroy just shrugs at this question. Chester struggles with staying patient: “The hardest part is that I really want to be finding a job. This isn’t getting me a job.” For Nate, the hardest part is that people he knows drive by. They notice that he’s out here, and he feels embarrassed that he’s not doing better for himself.

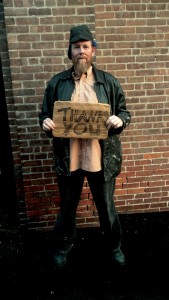

To get a better feel for flying, I spent an hour flying a sign on North Main St in Providence. Not wanting to lie, this non-homeless (for now) reporter’s sign simply said, “Thank you.” (That was probably my biggest mistake, Nate would tell me later – the sign is your communication to the world, “It’s got to be heartfelt and genuine, and say something,” he advises – see Nate’s sign in the photo).

The endeavor was mostly a waiting game. When the light is red, you have a shot. When it’s not, there’s not much to do. I found one light where I could amble slowly past the waiting cars on red, then walk back to the head of the pending line on green. I got some exercise. But I learned not to move too fast. Lingering, slightly but inoffensively, was the only way I managed to get any donations. I was flying for just over an hour and made $4, one each from four compassionate passersby [a ten-to-one match was passed on in turn by Motif to Crossroads, a local Providence homeless shelter]. The first person to give completely made my day – I’d been out for about 15 minutes with no one even willing to talk to me, so I may have looked a bit sad and depressed. He made eye-contact, then looked away. Then made eye-contact and looked away again. Then leaned sideways – a good sign that the driver’s reaching for a wallet – and gave me my first dollar. “I know it’s cheap, but this is all the cash I have. God bless you.” I was monumentally grateful.

For me, feeling like not-quite-a-human was the darkest part. People ignore you, when you know they’ve perceived you. They won’t look at you, and some went to fairly ridiculous lengths to look everywhere but where I was standing. “It’s their choice, you can’t let it bother you. They don’t know you, so it’s not personal,” suggests Nate. Still, I came to appreciate the folks who would look and nod, or the super bubbly blonde woman who waved and smiled like a displaced cheerleader, then made a larger than life sad face to indicate that she couldn’t give right now. Or the rough looking fellow who rolled his window down to say, “Sorry, buddy, I’m busted right now too.”

Next time I go out, I want to draw a sign that says, “Cardboard signs, $2” and see if I get any more play. My guess is I won’t – compassion, not humor, is the draw here; and even though I got four donors and over 200 no-eye-contacts, that dollop of compassion is uplifting in difficult times.

“You can’t care too much. There are good and kind people who go rolling by every once in a while, and you just have to wait. Be respectful – I never get out in traffic or try to get their attention. I just have my sign and my patience,” advised Leroy.

From inside the car, is it good or bad to give to the flyers? “There’s a study where they gave cash to people on the street and found it worked better than giving it to infrastructure,” said attorney Neville Bedford, referring to a recent study by economist James Sullivan of University of Notre Dame that followed a set of homeless and nearly homeless in Chicago, and which has yet to be replicated. The study found that giving directly to those teetering on the edge of homelessness has a bigger bang for the buck than funding infrastructural charities that help the homeless with services – a $1,000 direct investment and an investment of between $6,800 and $20,000 in a charity (depending on the organization) will produce roughly the same result.

But then there is a mixed bag in the flyer community – although many are looking to build their lives up, others are just looking for coffee and cigarettes to get through the day. Then there are the

ones working the system. “There’s a guy who works the corner up that way,” a source tells me, gesturing up North Main St. “He’s causing quite a stir around here, because he isn’t homeless. He lives in University Heights, and everybody knows he has a girlfriend who takes care of him. But he also has a problem with crack, which is why he’s out here, and where whatever he makes goes.”

Megan Smith, the outreach program manager for House of Hope in Cranston, is deeply involved in activism around issues relating to homelessness. “The two reasons I think panhandling is important,” she says, “are, first, it enables some people to meet their most basic needs in a really, really broken system … second is about creating societal dialog around poverty and inequality. To me that’s the most fundamental aspect of panhandling – the human transaction even more than the monetary one. I think if we don’t see an issue, we as a society can pretend it doesn’t exist – whether it’s racism or sexism or poverty. As long as there’s poverty, it’s important that poverty not be invisible.”

When it comes to the kind of laws Smith and her colleagues advocate against, Cranston leads in the state.

“Cranston has a statute called ‘Solicitation on roadways prohibited’ – an old law on the books,” says Smith. “When the new, majority republican city council come into Cranston, they took it upon themselves to create a new ordinance that had the same title but had details like, that you can’t panhandle on a street over 25 feet wide. On March 2, a group of us went out to challenge it (on Sockannosset Road near Emerald City). We got ticketed for defying that ordinance, and now we’re on the way to federal court to hopefully get the law knocked down as unconstitutional.”

All six defendants are represented by attorney Bedford. A temporary order has been handed down by the federal appeals court, preventing Cranston police from acting on the statute until those cases have made their way through the judicial process. So, right now, it is technically illegal to fly/panhandle in Cranston, but it is also illegal for the police to do anything about it if someone does.

Warwick and Providence seem likely to hold off on any similar laws until they see how things resolve in Cranston.

What else can you do to help? “Say hello to the people you see flying signs,” Smith suggests. “Whether you give money or not, roll down your window, smile, make eye contact. It’s fine if you don’t have anything to give – wish them well, say something encouraging. Any kind words. And then look at why we as a society have created an environment where this is the best option for people – where they can’t get what they need through programs like 211 or United Way. No one’s out there doing this for fun. It’s not fun. It sucks. Let’s use these examples to spark the larger conversation of having a social safety net that’s actually a social safety net.”

Other activities are offered in Providence – we talked to Victor Morente, press secretary for the mayor’s office, about the city’s attempts to deal with homelessness and related issues. “The mayor wants Providence to be a compassionate and forward-thinking city. One of the ways we’re doing this is [by working] with Amos House – the city’s allocated $200,000 for their [A Hand Up] program that provides opportunities for work to those who are homeless. They wear those nylon reflective vests and they do some type of cleaning; the Huntington Avenue has been cleaned by folks in the program. The mayor saw that as a good opportunity for those folks who need that little bit of extra assist to get back on the right path. There’s also a PVD gifts campaign … the focal point of that are the giving meters. Those are the orange meters (a map can be found at pvdgives.com). At the end, that money gets distributed to those non-profits that have a proven track record of providing services to those in need. We are also launching a service for those combating addiction, where you can walk into any fire station, 24/7, and receive addiction counseling; we’re launching that program on January 2. Last I checked – and that was before our drive on giving Tuesday, the new meters had reached about $500.”

Warming centers are set up on particularly cold nights in most RI area towns and cities – visit riema.ri.gov/warmingcenters for locations in RI. Massachusetts also has warming centers, but suggests calling 211 for their locations.

You can give to the House of Hope to support their efforts to help the homeless of RI at thehouseofhopecdc.org. You can find out more about Amos House programs at amoshouse.com

Follow-up (April 18, 2018): motifri.com/the-complaint-department