Graphic novel released in English

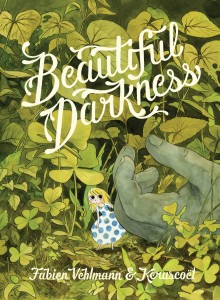

Beautiful Darkness, a 2009 graphic novel released in English for the first time this year by Drawn & Quarterly, is a study in contrasts. The book begins as a Disney-esque fairy tale in which the dashing Prince Hector comes to visit the lovely Aurora for tea. Chivalry and romance are in the offing until the world comes literally crashing down around our characters in the form of jelly-like organic droplets. Aurora, separated from her Prince and faithful servant, narrowly escapes drowning in a flood of viscous goo, only to emerge, along with a host of other characters from her fairy tale, out of the body of a giant girl who lays in the woods, freshly murdered.

Beautiful Darkness, a 2009 graphic novel released in English for the first time this year by Drawn & Quarterly, is a study in contrasts. The book begins as a Disney-esque fairy tale in which the dashing Prince Hector comes to visit the lovely Aurora for tea. Chivalry and romance are in the offing until the world comes literally crashing down around our characters in the form of jelly-like organic droplets. Aurora, separated from her Prince and faithful servant, narrowly escapes drowning in a flood of viscous goo, only to emerge, along with a host of other characters from her fairy tale, out of the body of a giant girl who lays in the woods, freshly murdered.

It is hard to know what the tiny characters emerging from the giant girl are thinking. Most are caricatures without depth, their one defining feature instantly recognizable as genre tropes. There’s a selfish Princess, a scheming servant, a fearfully shy wallflower, and characters who exist only for comedic relief. Detached from the mind of the giant dead girl, these characters are also cut adrift from the fairy tale narrative, free to exercise their virtues (of which they have few) and their faults (of which they have many) without fear of literary comeuppance.

The characters attempt to live in the woods around the body of the girl, but the local fauna, the bugs and the birds, and the natural elements, are not from the idyllic fantasy land they are used to. Unspeakable horrors befall the characters. When Aurora attempts to befriend the woodland creatures as might Snow White, she is instead greeted by feral, unintelligent and dangerous beasts. In her anger she is as cruel to the animals as the animals are to her people.

Slowly, the body of the girl begins to rot away. No one comes looking for the girl, save for a man who may or may not be the girl’s father, murderer or both. As the body of the girl fades away, as the real world ravages her youth and beauty, so too are the characters who formed the foundation of her fantasy life destroyed. The effect is terrifying, stomach churning, yet arresting and impossible to put down.

The art in this book is beautiful, delicate line work and watercolors that somehow blends the cartoonishness of the escaping fairy tale characters with the realistic depictions of insect, animal and plant life seamlessly. Each page is a miniature comic masterpiece, beautiful art that contrasts the horrific story being told. The artist, Kerascoët, (a pen name of Marie Pommepuy and Sébastien Cosset) maintains a website at kerascoet.fr, and there seem to be many more comic and illustration projects here that might be worthy of translation for a North American audience.

This is the story of innocence lost. Whatever happened to the giant girl is never really explained. There are hints and suggestions throughout the book, but the fairy tale characters, through whom the story is told, seem to have limited awareness. They do not always seem to understand the implications of their plight and seem to actively ignore the implications of what they do understand. They are forced into a fight for survival, and though some seem able to find a way to survive in this world, their small-mindedness makes them a terrible danger to each other.

On the back of the book other reviewers compare the work to Alice in Wonderland or Tove Jansson’s Moomin work, but neither comparison seems adequate to my mind. I would instead compare this work to the comics of Alan Moore, whose early work eagerly reinvented simple character in a modern, complex and psychological fashion, as in his Swamp Thing or Watchmen. But Beautiful Darkness goes deeper and darker than any of the work it’s compared to.

It seems an entirely unique creation.

This book is open to several different interpretations. At one point I suspected that the characters all represented various facets of the dead giant girl’s personality, and as the characters died, so did the girl’s presence fade from the world. On a second reading I began to suspect that the characters were more representative of the giant girl’s inner world. Again there is a contrast: narrative simplicity meets interpretative complexity.

This is a book of love, fear and transformation of character through horror. This is not normally my kind of book, and in lesser hands it would have been a chore to read. But the story by Fabien Velhman, based on an idea by Marie Pommepuy, held my fascination despite its existential bleakness, and as usual the publisher, Drawn & Quarterly, did a marvelous job putting the book together.