I am at DWRI Letterpress, and I am standing in front of a Linotype, the first automatic typesetting machine — a machine that Edison called the “Eighth Wonder of The World” — and over the whirring, clanking and spitting of its 3,000 moving parts, Dan Wood is explaining why it’s so wondrous, or in his words, “Completely insane! This started a whole new printing revolution: the second printing revolution after Gutenberg. Up until the 1880s, everything had to be handset — this machine made school textbooks affordable, and suddenly instead of two- or three-page newspapers you could have daily newspapers that were 20 or 30 pages long. It launched us into the information age.” At the turn of the century, the Linotype was a marvel of modern engineering; it was, in Dan’s words, “breathtakingly fast…and now it’s like, so, so slow.”

Dan would know. He’s the artist behind The Linotype Daily, and for 366 consecutive days (ending on Leap Day), he produced a new “print, card, pencil or other Linotype-created work” using this fin de siècle marvel. Dan’s website describes The Linotype Daily as “part diary, part news filter.” He had a number of print subscribers, and a spot in the World’s Fair Gallery,

but many encountered the project through the Instagram account @thelinotypedaily.

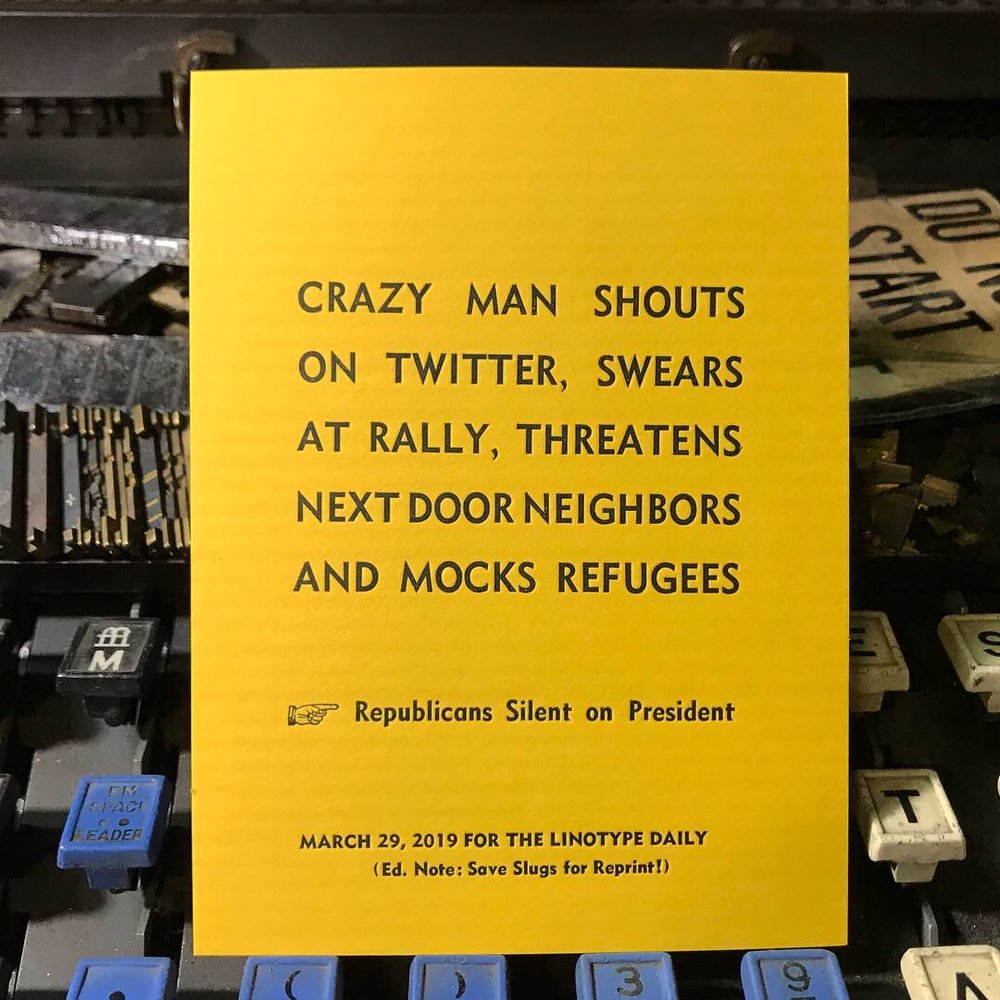

Dan’s daily posts toggled between the political (“PRESIDENT PARDONS WAR

CRIMINAL,”) and the personal (“TEENAGE WHISTLEBLOWER ALLEGES HER DAD ATE THE PEANUT BUTTER”), the local (“PRONK!”) and the national (“HONG KONG, BEIRUT, SANTIAGO! MILLIONS CONTINUE PROTESTS”). The voice of The Linotype Daily is that of a hard-nosed reporter of bygone days: authoritative and bombastic (“When you put it in print, people can’t hear my ‘every-sentence-is-a-question’ inflection”). The fonts, classic early-to-mid-century newspaper typefaces, carry a similar power, as does the printed word itself (“People think: ‘they wouldn’t print it if it wasn’t true.”).

There’s a wry irony in the juxtaposition between that authority and the content of the posts themselves, which reflect the dizzying, haphazard tone of our hyperactive news cycle (“THE WORLD IS STILL A MESS”). “It’s been such a weird year,” Dan says. “Day after day it’s worse and worse and everything is just so bizarre.” That absurdity comes out in the Daily,

sometimes as whimsy (a Democratic Debate scorecard modeled after an Olympic Figure Skating card), sometimes as despair (“I CAN’T KEEP UP!”), often as both.

Dan grabs a loose Daily from a nearby stack and passes it to me (“DEATH EATERS TRIUMPHANT! REPUBLICANS SILENT AS PURGES CONTINUE”). I run my fingers over the debossed letters as he muses: “I’m printing a hundred copies of this, but on the Instagram hundreds, thousands, whatever, all these people are going to see a digital replication of this

handmade thing, but because it’s handmade, they’re going to spend more time looking at it than if it were just, like, a meme. Which is a weird thing. But people like things that are handmade. The amount of time it took for you to make it seeps into its meaning somehow.”

Part of what makes The Linotype Daily intriguing is the allure of the tangible. The studio itself is a sensory playground: the lead bubbling in the crucible of the Linotype (in which old type slugs are melted and reborn); the chunk-chunk of the Heidelberg spitting out copies (“I can’t watch anyone using this machine because it looks like you’re sticking your hand in it,” Dan says, as he seems to stick his hand in it); the paper invitations and cards and posters that line the walls (including all 366 Linotype Dailies).

The studio is a veritable museum of archaic machinery, and the project is, to some extent, an ode to the analog. Making a single Linotype Daily took Dan between one and five hours: writing the post, setting the type, loading and operating the machines, selecting the typeface. Dan points to a card that says “IMPEACHED” — “This 96 point Gothic is a really weird typeface, it’s got this playful joy, it’s really strange.”

That so many people encountered and engaged with this staunchly old-fashioned art on social media adds a layer of irony that Dan seems both bemused and fascinated by: “It’s very, very strange.”

“[These days] there’s so much information that we’re not even capable of sorting through it … with the project it was kind of like … maybe taking the time to do this little thing will be a way to sort of navigate the information overload that we’re all living in.” Social media gave him a chance to turn that sorting, the processing of a chaotic year, into a dialogue with his audience. “I feel like speaking honestly is the artist’s only job,” Dan says. “Just doing that is creating some meaning. If you’re doing something you feel genuine about, other people will appreciate that.”

If you’d like to see The Linotype Daily irl, it will be part of a show at Galerie le Domaine (145 Wayland Ave, PVD), called “Our Ephemeral World: from Plants to Paper to Print,” on the first Gallery Night of 2020, March 19 from 6 – 8pm. The posts are also available for purchase through dwriletterpress.net