It’s not surprising that academic researchers have tried to define and even quantify love, but it is somewhat surprising that they only have been doing so since tentative explorations in the 1970s and more substantially in the 1980s.

Leading researchers on the subject Clyde and Susan Hendrick devoted a chapter to “Love” in Liking, Loving, and Relating (1983), a book aimed at clinical therapists rather than researchers. It is difficult even to distinguish “liking” from “loving,” they write: “‘I love only you’ is considered highly appropriate when uttered in the right context to the right person. ‘I like only you’ would be considered by most people to reveal a stunted personality and an inability to relate properly to people. How would you feel if someone confessed that he or she liked only you in the whole world? Probably your desire to escape would be stronger than your feelings of flattery.” It is even possible to love someone you don’t like, a seeming contradiction but a fact borne out in practice.

Exclusivity in relationships has warranted its own research attention, notably in the anthropology best-seller Sex at Dawn: The Prehistoric Origins of Modern Sexuality (2010) by Christopher Ryan and Cacilda Jethá that asserts humans were non-monogamous before the invention of agriculture, a controversial claim that has been widely criticized on scientific grounds, notably by Lynn Saxon who wrote an entire book in refutation, Sex at Dusk: Lifting the Shiny Wrapping from Sex at Dawn (2012). Other than achieving status as a best-seller, it hardly broke new ground on matters thoroughly explored in the scientifically more respected The Myth of Monogamy: Fidelity and Infidelity in Animals and People (2001) by David P. Barash and Judith Eve Lipton: “In attempting to maintain a social and sexual bond consisting exclusively of one man and one woman, aspiring monogamists are going against some of the deepest-seated evolutionary inclinations with which biology has endowed most creatures, Homo sapiens included.”

The key insight from the body of research, however, is that there does not seem to be any single path of love relationships that can be taken as “normal,” but rather there is enormous variation among individuals reflected in even the most basic vocabulary: one person does not necessarily mean the same thing as another person when using the same words.

(Source: Kaitlindzurenko, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

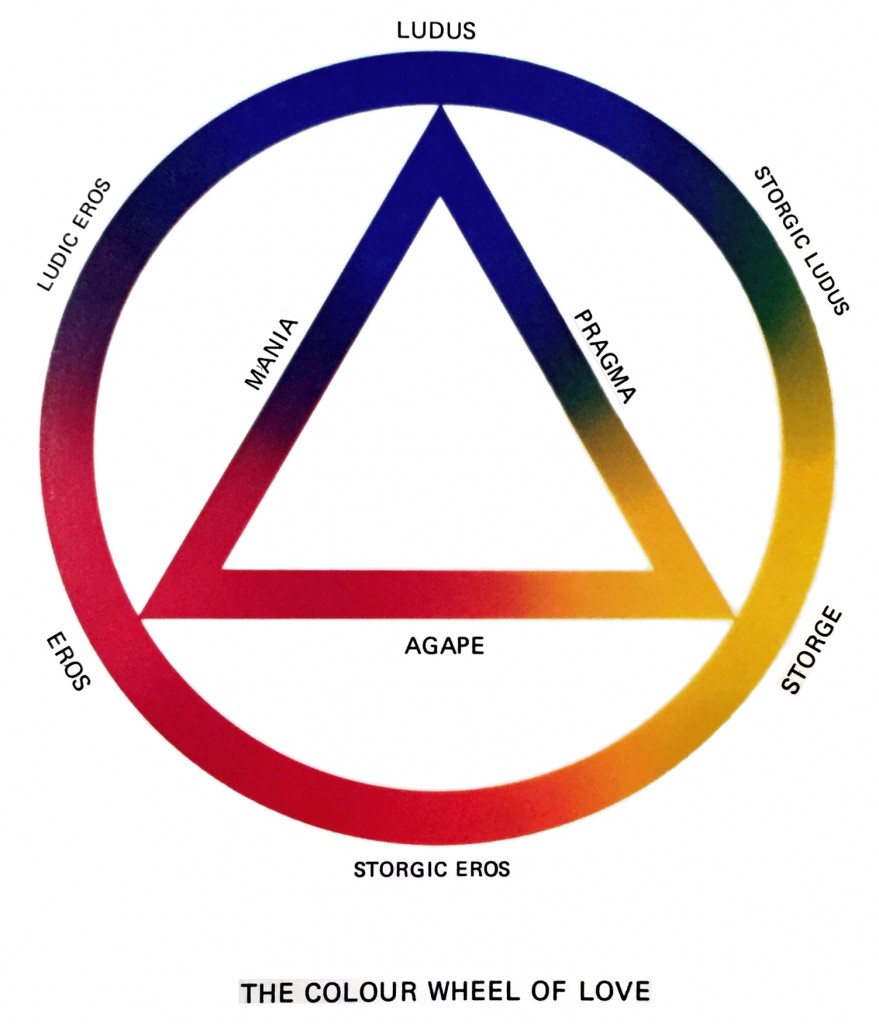

The seminal research was carried out by sociologist John Alan Lee and published in his The Colours of Love (1973) – he was Canadian, accounting for his spelling of “colours” – in which he invoked the metaphor of the color wheel, identifying three primary “love styles” that combine into either compounds or mixtures. Lee interviewed subjects about their experiences with romantic relationships, eventually formulating a standardized questionnaire that determined how an individual placed on a number of scales correlated with the primary and secondary styles. Lee’s model has three primary scales that, using various Latin and Greek terms, he named:

• Eros – intense physical and sexual attraction, wanting to be together as much as possible, comparing a partner to an idealized image, prone to “love at first sight.”

• Ludus – seeing relationships as play, often with multiple partners either serially or simultaneously, wanting to engage in activities together, prone to engaging in gamesmanship and maneuvering for advantage while “keeping score.”

• Storge – love as an extension of friendship, often developing unexpectedly, able to withstand substantial physical separation, sexual attraction as a consequence of commitment.

Lee’s secondary scales are based on the primary ones:

• Pragma (combination of Storge and Ludus) – emphasis on practical considerations, relationships as business partnerships, accepting arranged marriages.

• Agape (combination of Eros and Storge) – love as self-sacrifice and generosity, taking care of someone else.

• Mania (combination of Eros and Ludus) – worshiping and needing a partner to reinforce one’s own identity, feeling lost and purposeless without a partner.

Each of these traits has advantages and disadvantages, although some weigh more heavily to one side or the other. Mania, in particular, is almost always disadvantageous, leading to co-dependence and obsessive jealousy. Agape can turn into martyrdom and vulnerability to abuse and exploitation. Pragma often violates cultural norms, where one partner bringing an actual checklist into a relationship may be seen as logical by the one doing it but indicative of lack of genuine feeling by the other.

Clyde and Susan Hendrick in 1986 revised Lee’s model and dispensed with the color wheel metaphor, simply measuring the six scales (keeping his names for them) in what they called the “Love Attachment Styles” assessment consisting of 42 statements, each of which has five possible responses from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree.” The Hendricks, psychology professors at Texas Tech University until their retirement in 2015, established correlations between love styles and attitudes toward sexuality (developing their “Sexual Attitudes Scale” in 1987) as well as gender differences. Numerous researchers established correlations between love styles and long-term happiness, finding that Eros and Storge love styles between similar partners correlated with happiness, and Ludus correlated with unhappiness. The Hendricks provide a thorough overview of the subject, including a discussion of alternative theories, in their article “Romantic Love” in the graduate psychology textbook they edited, Close Relationships: A Sourcebook (2000).

Once becoming acquainted with these theoretical models of romantic love developed by modern psychology, it is easy to see examples in literature and cinema from decades and even centuries earlier. Mania is a particular favorite in fiction (Endless Love, Fatal Attraction) given its appearance in extreme form as dangerous mental illness. A good argument could be made that Shakespeare at some point employs all or nearly all of the six traits, such as Pragma in Macbeth, Ludus in The Taming of the Shrew, Agape in Hamlet, and Mania in Romeo and Juliet.

The most successful relationships are likely to involve partners who share similar love styles. When relationships go severely wrong, Lee’s model argues, often it is because partners have incompatible love styles. Having sex on the first date, a common characteristic of Eros who logically wants to avoid wasting time if physical attraction is absent, would be incomprehensible to Storge, who develops physical attraction only in the context of a relationship, and would be foolish to Ludus, who sees sex as an asset to be exchanged within the rules of a game. Just as first-date sex is almost defining for Eros, so is a partner checklist defining for Pragma and a “little black book” defining for Ludus. Partners with incompatible love styles literally are not speaking the same language.