Walking into Nick McKnight’s neon studio in Providence, I immediately see the signature glow of neon. The studio, Night Light Neon, is warmer than the warehouse-type building it is housed in. The signs are kicking off heat. There is a sign on the opposite wall that demonstrates the different colors of neon in two columns, and I hear the voice of my elementary art teacher in my head teaching me about ROYGBIV.

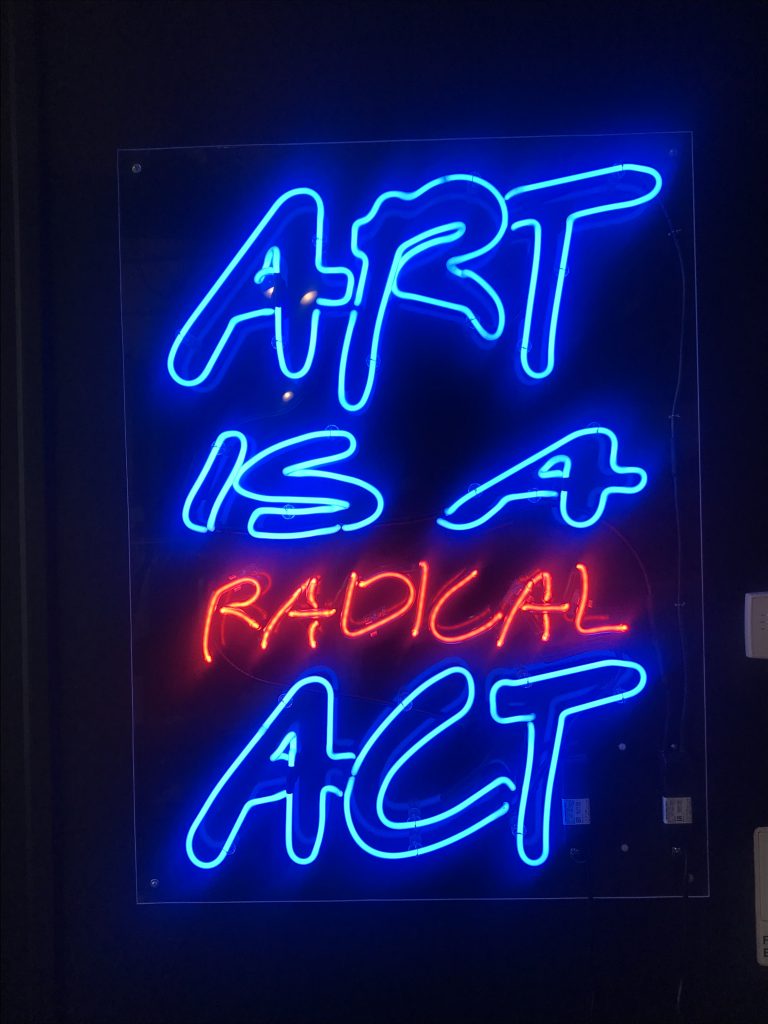

You don’t need mnemonics to remember the colors of the rainbow in here, in fact, there is a sweet little neon rainbow hanging on the wall, along with dozens of other neon signs that McKnight has either collected, made, or repaired. There’s a pig segmented into its parts, a butcher’s sign, a vintage-looking Budweiser logo, barber’s scissors hanging from the ceiling — their light turned off and their blades cocked open, ready to snip. There are simple words: “HOT,” “OFFICE,” and “DAIRY.”

The left column of the sign of neon color swatches is headed by the letters “Ar,” the right column is headed by “Ne.” Mcknight explains that the two columns represent the two most common gasses used in neon making. “Ne” colors are “clear glass with the gas of neon pumped into it. The other one is Argon with a dab of mercury in there.” He explains that the variations of colors are created using different phosphors, a different mix for each color. He notes, “The namesake is neon but most colors are argon.”

Outside, the colors are being mixed, too. I visit the studio on a bright blue day in late February. We joke about Punxsutawney Phil and his fuzzy prophecy foretelling of an early spring. Every year it comes as a surprise — new life on its way after another gray winter.

In the FAQ section of the Night Light Neon website, it states: “The name neon is derived from the Greek word neos, ‘new.’” While the novelty of neon feels as fresh as ever, the first neon tube lighting was unveiled at the Paris Motor Show in 1910 by French engineer Georges Claude. According to the Neon Museum of Las Vegas, following the patent of Claude’s invention, “the first use of a neon sign is believed to have been by a Parisian hairdresser in 1912.” Meanwhile, neon signage wouldn’t be used in America until the 1920s, where it spread like a wildfire of vibrant, larger-than-life advertising.

Noting the dwindling popularity of neon, McKnight says it’s “come in waves since the 50s. There’s been a decade of neon at its height then nothing. Another decade at its height, then nothing. We’re at the end of the heyday right now, but it’ll keep going back and forth.”

McKnight got his start as a neon artist, or “bender,” about 10 years ago. He had worked as an artist, in the event industry, and as an assistant to a glass artist, when he got the opportunity to work at a sign shop in Connecticut when a bender was retiring. He recounts, “I interviewed, and he had me come into the neon shop just to mess around. I was there for five hours. He came in and was like, ‘You’re still here?’”

Since then, McKnight has worked to become a master bender, eventually starting his own shop in Providence last August. He has recently done repairs for neon signs at Baba’s Original NY System and Olneyville NY System, working to restore and replicate their neon to its former glory. He also does rentals and commissions. If you watched Good Burger 2, you may have noticed his golden hamburger in the background of some scenes. His diver lady, clad in a red bathing suit and swimming cap, illuminated the window of World’s Fair Gallery on Broadway last summer, along with other featured works.

While the initial neon industry was male-dominated and insular — McKnight tells me that a lot of early benders were generational, with the art passed down from father to son — but neon benders nowadays work to share resources and support one another. In fact, McKnight is one of the co-founders of Neon Makers Guild, which is “an organization dedicated to the preservation of the craft of neon,” according to its website.

He walks me through the process of making neon, which begins with making a pattern that is inverted and flipped. He selects the diameter of glass tubing for the project and begins marking it alongside the pattern, indicating where he will bend the glass in turns. Next, he says “a cork is placed in one end of the tube, and a blow hose in the other. The bend is made, and I lightly blow into the tube to keep it from collapsing/keep the diameter of the tube uniform.”

Once the glass is shaped, he hooks electrodes to the ends and uses a vacuum that clears out any impurities in the glass tubing. He hooks the structure up to about 20,000 volts and heats it up. The tubing has to be completely clean and dry, with the electrodes heated up properly. Finally, he backfills the glass tube with the gaseous mixture of either argon, neon, or another noble gas, depending on the color.

“It’s never not stressful. You get into muscle memory, but I’ve wanted to quit hundreds of times over the years. It’s frustrating.”

So why neon, an expensive, frustrating art form with dwindling materials and a history of trade secrecy? To McKnight, “There’s nothing like it. It’s very energy efficient and if installed properly, it’s safe.”

As brightness emerges this spring — chartreuse buds glowing on the formerly bare tree branches and neon violets cracking through a hardened topsoil — keep an eye out for McKnight’s neon in shop windows and galleries among the other blazing colors of the world, something new and old at the same time.

For more information, visit nightlightneon.net or check out @nightlightneonstudio on Instagram.