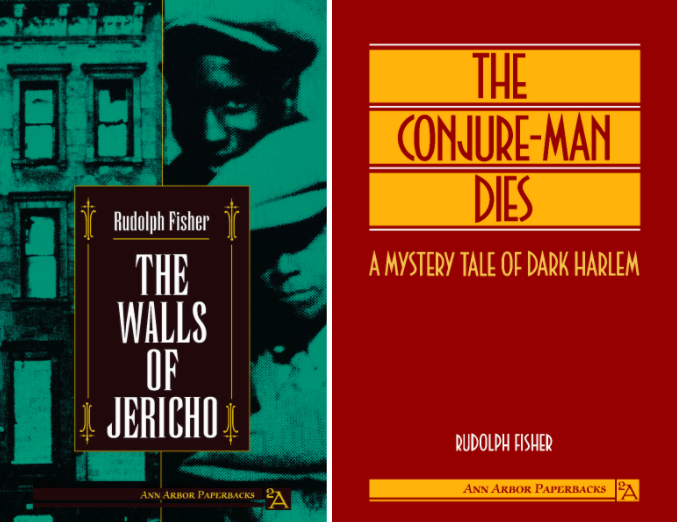

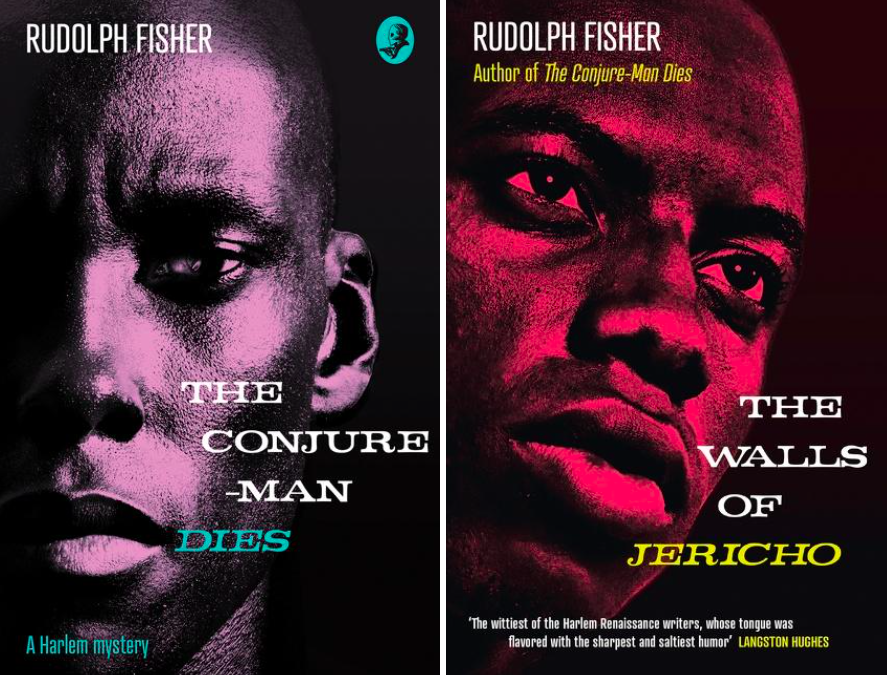

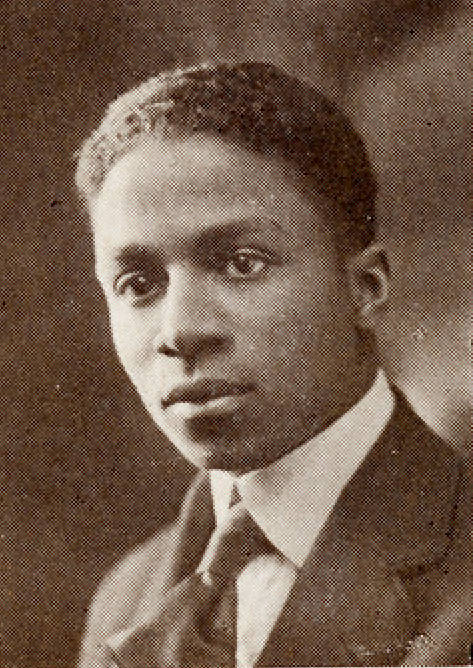

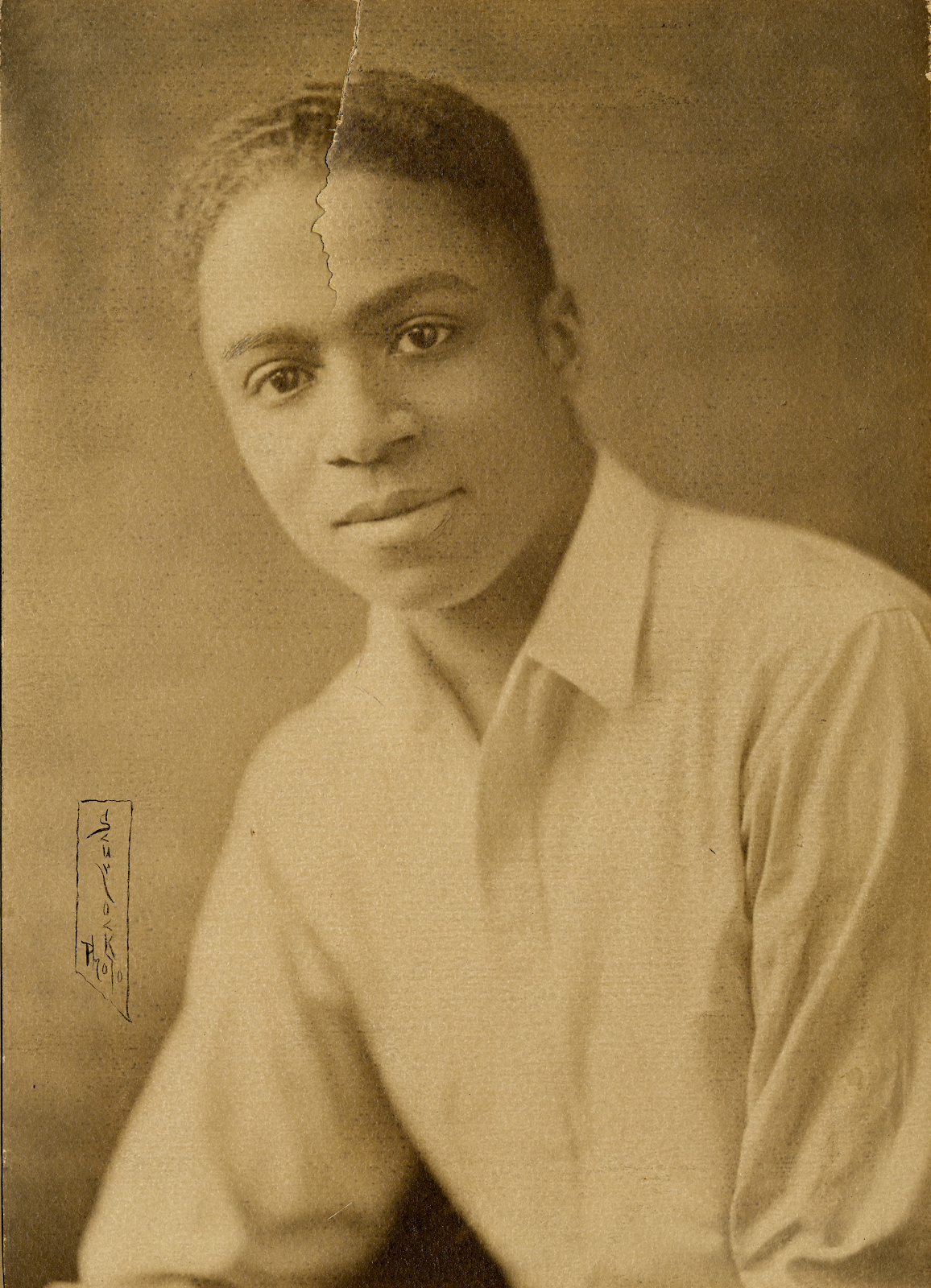

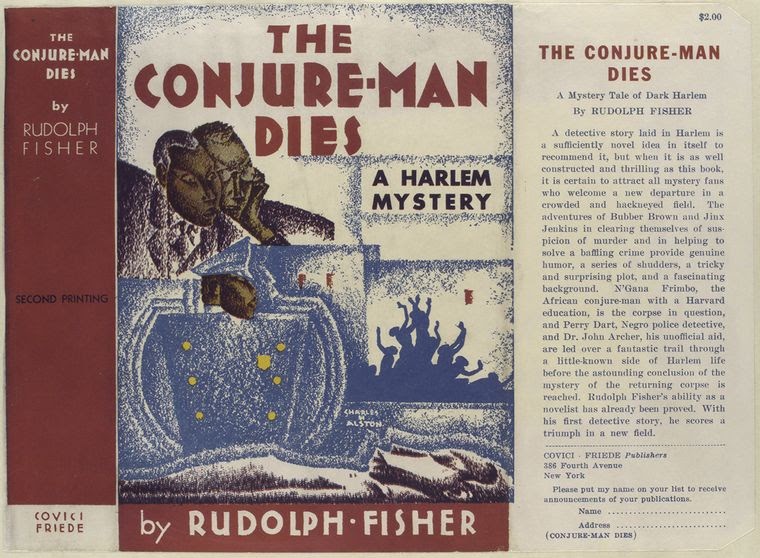

When, in 1932, Rudolph Fisher’s The Conjure-Man Dies was published, the journal Opportunity called the mystery “startling in its cleverness,” predicting the protagonist, a Harlem doctor with a detective’s eye, would reappear. That year, Agathie Christie spun her investigative hero, Hercule Poirot, into a seventh book and William Faulkner’s Light in August reflected the weight borne by a country whose stories were rife with racial classifications. Reissued this month by HarperCollins, Fisher’s work trod themes familiar to his contemporaries while breaking ground not only as the first known crime novel by a Black author, but also as the first to feature exclusively Black characters as they contend with a resurrected murder victim who promises, “He who knows completely the past and the present can deduce the inevitable future.”

An early witness to the migrations and voices that would later breathe life into his fiction, as a toddler Fisher shared a Manhattan apartment with his mother and father, a brother almost 20 years older who had served with the 25th Infantry Regiment, a Black unit given the military’s segregation, a teenage sister still in school, the ghosts of three siblings dead, and a waiter, houseworker, and bellhop from below the Mason-Dixon line paying rent as boarders. Within the tenement, Fisher’s neighbors were a mix of native New Yorkers and newcomers from the West Indies. Afro-Cuban essayist and editor Rafael Serra lived in the building next door. On the other side stood a lodging house of European immigrants, most of whom had arrived from Germany.

The New York Times described the stretch near West 33rd Street and 7th Avenue, one block from Broadway, as a “little principality” and “the despised ‘patch.’” Before his family arrived, a woman burned her roommate to death in an adjacent building, and a paperboy lost his leg when struck by an electric streetcar. Across the street, police raided the home of women dubbed the Three Musketeers for reportedly stage-managing thefts from “innocent wanderers” when rations were light. On the corner, a hotel offered a breakfast menu of English mutton chop, broiled quail on toast, and a side of Russian caviar, with Moët & Chandon Brut Imperial available by quart or by pint. After the funeral of a police officer, a white mob ransacked Black businesses, striking residents with clubs and clamoring for lynchings in the streets. Two avenues westward, the Thirty-Third Street Baptist Church preached salvation, and a local pastor wrote to the mayor for help on Earth: “The color of a man’s skin must not be made the index of his character or ability.”

With construction planned for Pennsylvania Station and railroad lines connecting New York with the South, tenement owners began to sell their properties, and many residents found themselves moving up to Lincoln Square and Harlem. Fisher’s father, a pastor, received an assignment farther north: in Rhode Island. When the Fishers arrived in Providence, electric streetcars shuttled along Broad Street, running between downtown and the city’s south side. In the shadows of the Union Railroad storage station, in September 1906 Rev. Fisher purchased a vacant lot for $10 (today: $2,900). On the site, he established the Macedonian Baptist Church.

As Rhode Island’s manufacturing economy surged, more than 100,000 new residents within a decade pushed the population above half a million for the first time. The state’s Black population increased by 437 to surpass 9,500 — fewer than the New York City neighborhood of Fisher’s early childhood. Of the dozen other houses on their Providence street, all but the next-door neighbors were white, mostly immigrants and children of immigrants from Canada, England, Ireland and Germany working as servants, bakers, box cutters and machinists. While Fisher’s father built the church, his mother worked as a dressmaker at home. By 1910, church records noted Fisher’s father’s efforts were “proving a vigorous offspring,” with a congregation of 60 members.

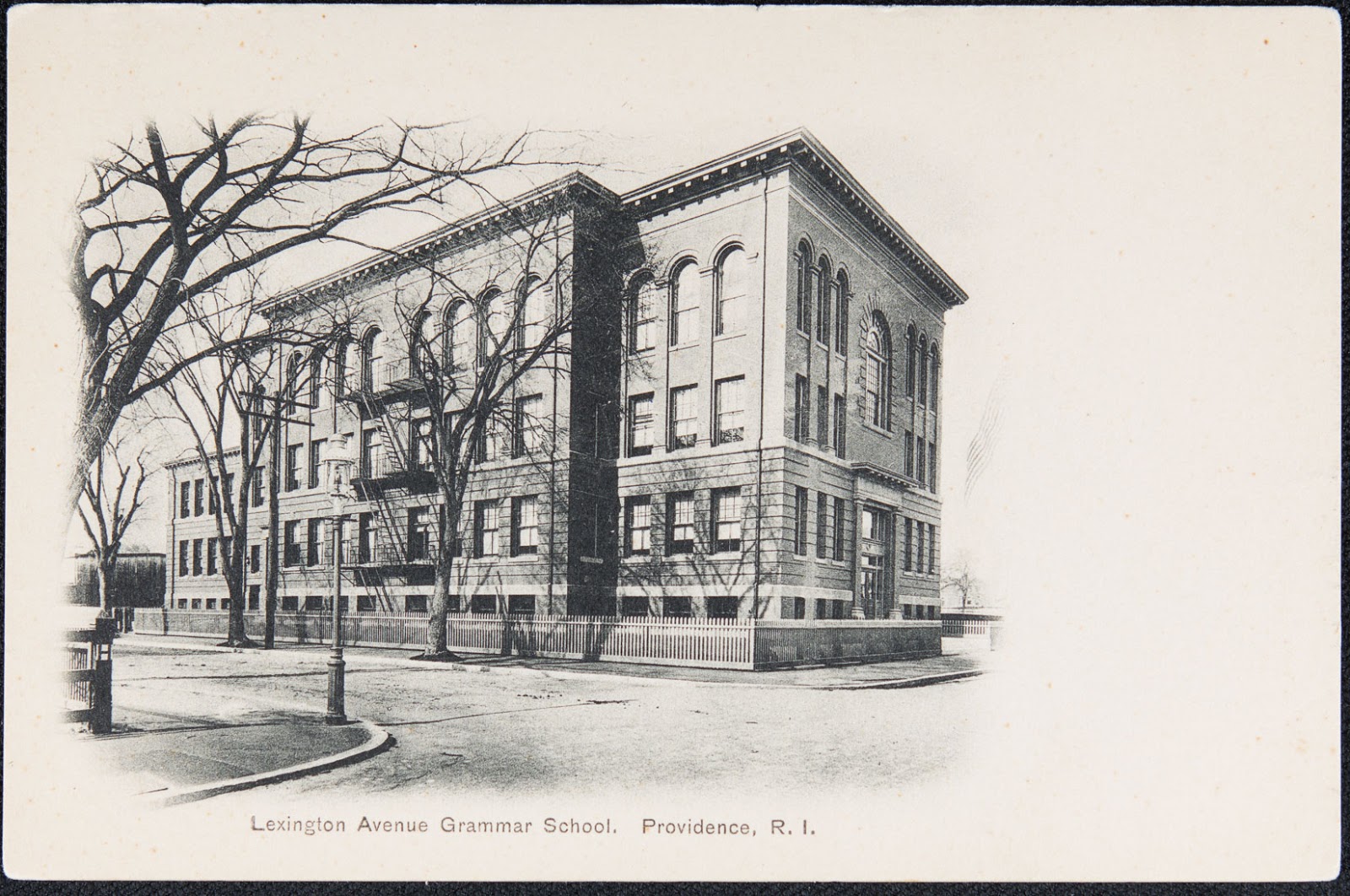

In the mornings, Fisher walked less than five minutes to a red-brick schoolhouse beside a gold and silversmith factory. As a student, he earned recognition for his writing, oration and music. At 11, to mark Abraham Lincoln’s birthday, Fisher recited in the main hall an ode to “a great soul passed from earth.” Three months later, he conjured the “tumult in the city” during 1776, rattling off verse about the Independence Bell ringing out for “glorious liberty.” With his school’s Glee Club, Fisher performed the works of Franz Schubert and delivered a solo recitative.

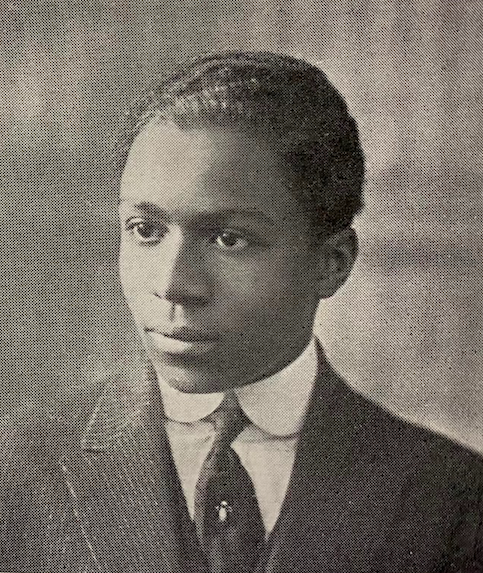

When Fisher entered Classical High School, the college preparatory program fell under the leadership of principal William T. Peck, a devout Baptist who had served as a delegate at a Rhode Island Baptist State Convention at the same time as Fisher’s father. At first, he avoided extracurriculars, but he returned to glee as a sophomore and added debate during his junior year. As a senior, Fisher served as treasurer of the former, president of the latter, associate editor of the yearbook and class poet. Of the languages taught at Classical, he opted for German over Greek, and expressed an intent to pursue medicine, hoping to study surgery.

Throughout high school, Fisher showed confidence on stage. At 16, he joined Rhode Island’s lieutenant governor to speak about Lincoln. At 17, he recited James Whitcomb Riley’s poetry at a school ceremony and led the debate team to win the state championships. At 18, he riled up his class dinner, delivering a speech The Providence Journal described as “replete with witty sallies, and enthusiastically applauded.” Other students dubbed him a “silver-tongued orator” and “the genius of the class — at least in extemporaneous brilliance.”

“The way apparently unpronounceable words flow from Fisher’s fluent tongue is indeed a revelation,” read his senior yearbook, “and it has certainly caused us unlimited worry to learn how he manages to swallow so much of the dictionary during the lunch period.”

Fisher’s principal urged the graduating class “to decide where to go in life and then get there.” Jim Crow laws limited how much Fisher could follow the same advice as his classmates.

Fisher entered Brown University as one of two Black students in his class. Pursuing a dual major in English and biology, he received the Caesar Misch Prize for German, placed first in the Thomas Carpenter Prizes for Elocution, and earned university scholarships for “exceptional scholastic ability” and being “the student with the highest standing in rhetoric, English composition, and public speaking.”

At a time when 1,800 Black residents of Providence marched in solidarity with silent parades held across the United States to protest lynchings and other killings on the basis of race, Fisher opened a civil forum on current issues with a musical program and hosted an afternoon lyceum to welcome public discussion.

After the United States entered the First World War, Fisher registered for the draft. Of the descriptions listed on his registration card — “White, Negro, Indian, and Oriental” — he crossed out three. Donning a khaki uniform and Montana peak hat, he drilled on campus with the Student Army Training Corps.

Weeks into Fisher’s senior year, the outbreak of the 1918 influenza pandemic led to Brown announcing a quarantine order and placing armed guards at the campus gates. Even as the war came to an end in armistice, commencement exercises the following summer bore a somberness given the dead and wounded overseas as well as the pandemic’s harm at home. A brass band led Fisher in the procession of graduating students down the hill from campus, as an honor flag displayed 42 gold stars, one for each of Brown’s former students and faculty lost in the war — more than half of whom had died from illness rather than in active battle.

Fisher served as orator during Brown’s commencement program and was selected as one of two class speakers. Noting his plans to pursue a medical degree, the Brown yearbook issued its own prescription: “Between soothing syrup and that glib tongue of yours, you ought to be a sure cure for anything.”

Less than six weeks after commencement, Fisher’s father died at home. His kidneys failed after a year of nephritis, a condition more likely following exposure to the 1918 influenza strain. Widowed, Fisher’s mother moved back to New York, finding work at the Colored Orphan Asylum in the Bronx. As a “Cottage Mother,” she helped with the care and education of nearly 300 parentless children classified as “inmates” in the 1920 US census. Fisher returned to Brown in the fall to complete a master’s degree, then enrolled in medical school at Howard University in Washington, DC.

Commuting to Howard from Baltimore, where his sister taught at the Colored Teachers Training School (today: Coppin State University), Fisher studied radiology; taught courses in embryology; led lab studies on chicken, pig and human embryos; and played fullback on an intramural football team. Under the banner of Howard’s motto, “Humanity First,” Fisher earned his Doctorate of Medicine as one of 27 graduates in 1924 and accepted an internship at the affiliated Freedmen’s Hospital, founded decades earlier as a Union Army barracks that provided medical care to those who had escaped enslavement or had been displaced by the Civil War.

Although Fisher told his Howard peers he planned to practice medicine in Egypt, he remained in Washington, DC, married his girlfriend, Jane Elsie Ryder, and began to submit short stories he had written around his medical work. In February 1925, The Atlantic Monthly carried Fisher’s first piece of fiction. The issue also featured “an original unpublished ballad” by Abraham Lincoln and an essay on the former president by an assistant secretary in his administration. Fisher’s “City of Refuge” captured the awe of King Solomon Gillis, a neophyte in New York who had “probably escaped a lynching” in North Carolina after he stepped off a subway in Harlem feeling “as if he had been caught up in the jaws of a steam-shovel, jammed together with other helpless lumps of dirt, swept blindly along for a time, and at last abruptly dumped.”

As other stories of Fisher’s began to appear, Alain Locke anthologized an excerpt from “The South Lingers On” in his definitive collection of the era’s Harlem literature. The Atlantic hailed the author’s “profound understanding of his race.” And The Crisis, the official magazine of the NAACP, selected Fisher as the recipient of its $100 Amy Spingarn prize (today: $1,500), judged by Charles W. Chestnutt, Sinclair Lewis, Mary White Ovington and H.G. Wells.

A National Research Council fellowship at Columbia University in 1925 gave Fisher reason to return to New York. The residence of his childhood had long since been demolished during the construction of Penn Station and rebuilt into Gimbels, a 12-story department store. With his wife, Fisher made a home in Harlem. While studying bacteriology and pathology at the College of Physicians and Surgeons, he also found friendship among other writers, musicians and artists. In May 1926, Carl Van Vechten welcomed Fisher with his wife and sister after dinner to meet publishers Blanche and Alfred Knopf.

When Fisher’s debut novel, The Walls of Jericho, fell into the hands of readers in 1928, Knopf trumpeted its latest voice from Harlem as a work in line with Nella Larsen, James Weldon Johnson and Langston Hughes. Bearing the title of a short story in Paul Laurence Dunbar’s 1903 collection, Old Plantation Days, and with reference to the biblical Book of Joshua, Fisher’s satire descended upon the nuance of race, class, labor and wealth. In an interview with Vincent McHugh for The Providence Journal, Fisher said he drafted The Walls of Jericho “in great haste.”

“Its impromptu form suggested that it had been done with the left hand but I had never before seen the evidence of a left hand so skilful,” noted McHugh. “I should like to see what Dr. Fisher’s right hand can do.”

During the preceding years, Fisher had managed a second fellowship from the National Research Council, practicing medicine at Mt. Sinai and Montefiore Hospitals. He conducted research into ultraviolet rays, co-writing papers with his findings for the Proceedings of the Society of Experimental Biology and Medicine and the Journal of Infectious Diseases. Fisher continued to contribute to The Atlantic and had fiction in the pages of McClure’s and reportage on white New Yorkers’ intrigue of Harlem in American Mercury. Amidst it all, he and his wife welcomed their only child, Hugh.

The end of the 1920s started for Fisher with the death of his mother. As the Great Crash ushered in the Great Depression, the private hospital where Fisher worked fell into financial trouble and changed hands. He continued in the role of superintendent under the new ownership of the facility, which too fell into bankruptcy. He paid $90 monthly (today: $1,350) to live in Harlem’s Dunbar Apartments, the first large-scale cooperative housing complex in New York built with a purpose of welcoming Black residents. Fisher’s brother, a postal clerk, and sister, a public school teacher, lived with him, his wife, and their son. They listened to radio broadcasts together, and Fisher wrote by typewriter for four hours in the mornings before work.

Fisher enlisted in the US Army as a member of the reserve medical corps with the 369th Infantry. And as an employee with the New York City Department of Health, he opened his own radiology practice at a family residence in the Jamaica neighborhood of Queens. The City Record, the official journal of New York City, misclassified Fisher as a veterinarian.

When Fisher’s second novel, The Conjure-Man Dies, was published in 1932, The New York Times called the follow-up to The Walls of Jericho “a puzzling mystery yarn which is at the same time a lively picture of Harlem.” The Crisis found it to be “a thrilling tale which is bound to be hailed the most unusual mystery of the year.” Opportunity, the journal of the National Urban League, argued that “firsts” like Fisher’s were “all very well indeed” and “should be noted” but instead of the work being “a good detective story” defined by the author’s race, it was all the more appropriate to conclude without qualifier, “it is a good detective story.” The reviewer predicted the protagonist, a Harlem doctor with a detective’s eye, would live on.

As Fisher conducted radio interviews, drafted an adaptation of the novel for the stage, published additional short stories, and continued his medical practice, a “stomach condition” led to multiple surgeries. While few reports surfaced about the precise cause or condition of Fisher’s health, The Crisis noted when he had received a diagnosis of “a heavy cold.” On December 26, 1934, as The New York Times reported on “the merriest” Christmas holiday since the Great Crash, Fisher passed away at Edgecombe Sanitarium in Harlem. He was 37 years old. The Times noted he had suffered “a long illness.” The Providence Journal reported it had been “a short illness.” Three days later, he was buried beside his mother in the Bronx.

Zora Neale Hurston transmitted a message by telegram to Fisher’s wife: “The world has lost a genius. You have lost a husband and I have lost a friend.” Langston Hughes later wrote, “I guess Fisher was too brilliant and too talented to stay long on this earth.”

Days later, a posthumous short story was published in Metropolitan, carrying Fisher’s detective-like doctor into another mystery. With support from the Federal Theatre Project of the Works Progress Administration, in 1936 Orson Welles brought The Conjure-Man Dies to the stage of the Lafayette Theatre in Harlem. Fisher’s wife and son kept his copyrights active, and his sister retained drafts of Fisher’s manuscripts, family correspondence and other records, which found their ways into the archives of Brown University, Emory University and the New York Public Library’s Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. But with time, Fisher’s legacy faded.

“He was actually one of the leading figures of the Harlem Renaissance,” said Delia Steverson, an assistant professor of African American literature at the University of Florida. “He characterizes this assertiveness, this pride, this independence, this unadulterated creativity.”

More than 50 years passed after Fisher’s death before the University of Missouri Press compiled a collection of his short stories. In the 1990s, the University of Michigan Press reissued both novels. A now defunct London publisher included Fisher as Black Classics, and Fazi Editore in Rome brought out an Italian translation, Dark Harlem. After a 2017 hardcover edition, in January HarperCollins released The Conjure-Man Dies as a paperback and e-book, with The Walls of Jericho due to follow in May.

“When these books are published, there needs to be fanfare,” said Ray Rickman, executive director of Stages of Freedom, a nonprofit that promotes Black cultural events in Rhode Island. “It needs to be orchestrated, and there’s no orchestra leader.”

Rickman features Fisher during Stages of Freedom’s cultural walking tours in Providence. The organization is fundraising to establish a museum about Rhode Island’s African American history, and Rickman said the nonprofit is in discussions with the Classical High School Alumni Association to produce a booklet and display on Fisher for students and libraries. In recent years, artist Sandra Smith stitched both of Fisher’s novels into a square on a wall quilt commissioned for Roger Williams University, and the Rhode Island Black Historical Society and the Rhode Island Historical Society have curated exhibits featuring the life of the author.

At the University of Florida, Steverson included Fisher among two dozen literary figures and publications for a Wiki Education project to improve the quality of Wikipedia entries related to the African diaspora. Students in her survey course on African American literature conducted research, presented their findings in class, and drew from 275 references to make nearly 800 edits to improve the Wikipedia pages of their assigned topics. Within two months of their semester’s conclusion, their updated entries were viewed almost 40,000 times.

“Work like Wikipedia is going to help to provide open access to knowledge and help to fill these equity gaps,” said Steverson.

“Fisher demonstrates how certain Black voices get lost throughout time,” she said. “What we don’t want is for Rudolph Fisher to be lost in translation for the next 50 years or the next 100 years.”