As the new year rolls along, still chock full of anxiety and loneliness, a seafaring music genre that peaked in the 19th century has become an unlikely star on TikTok. The trend started when 26-year-old Scottish mailman Nathan Evans posted his version of the sea shanty “Wellerman,” a whaling song with origins in New Zealand. That triggered a full-blown frenzy, with hundreds uploading their own riffs.

Sea shanties are maritime songs sung to accompany various ship deck tasks like sail hoisting. They combine the rhythms of African work songs with lyrics that are Anglo-Irish, often in 4/4 time with simple melodies that make them a good fit for mass consumption.

Some say the popularity of the sea shanty, meant to be sung together in support of a common goal, speaks to the desire for connection during these dark times. On the other hand, Vox contributor Rebecca Jennings sees it as the next in a series of random crazes driven by the social media hivemind: “The quarantine-era internet just makes us cycle through obscure niches of culture faster and faster,” said Jennings.

So what is it about these sea shanties? I spoke to local expert Mark Lambert of Providence’s Sharks Come Cruisin’, who specialize in sea shanties, about his experience with the unique genre.

Lambert grew up playing in punk and hardcore bands in Providence. His band, Return Around, fizzled out at the end of a long tour at which point he took an extended break from music. He wanted to start playing again in the early 2000s, but wasn’t sure what shape it would take. “A lot of my peers from the rock scene were gravitating to country or blues, which didn’t really seem all that authentic to me.”

One day, Lambert was watching the movie Jaws, which features a few shanties, and was immediately taken. “I heard Quint’s version of ‘Spanish Ladies’ — I knew there was something very New England about the sound, and it felt very close to home for me,” he said. After borrowing some sea shanty LPs from the library he dug in further, working out the songs and playing local open mics. SCC started to take shape once he got a bassist and drummer involved.

On a musical level, the appeal for Lambert makes sense. Three chords, an everyman spirit and a supremely singable nature make shanties not unlike punk rock. “The melodies are all very familiar — even if you don’t know them, you kinda do,” said Lambert.

The call and response element, which helped shiphands stay in sync when performing heavy-duty chores, was another big draw for Lambert. “It reminded me of exactly where I grew up at hardcore shows — the singer was singing and the audience screaming back at them.”

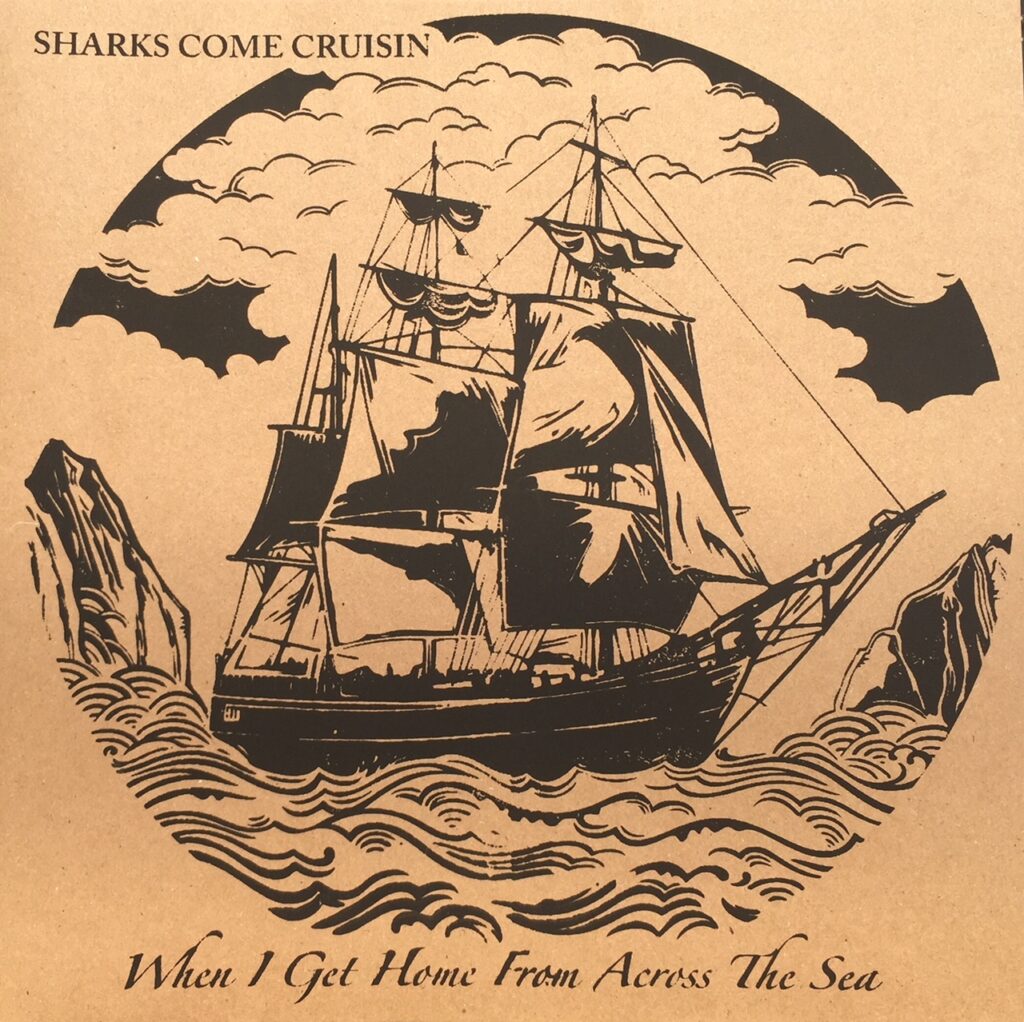

SCC, to date, has two full-length albums, along with various EPs and live recordings mostly consisting of traditional shanties and the odd original mixed in. Lambert’s punk background really shines through in songs like “South Australia” and “Donkey Riding” off their album When I Got Home From Across the Sea, which are uptempo, semi-rocked out shanties. Instruments like banjo, fiddle and accordion round out the sound.

The band has also become known for the monthly Shanty Sing at the Parlour, the rare family-friendly evening gig. Lambert came up with the idea and pitched it to then part owner Aaron Jaehnig, and it ended up being a major success. SCC had been doing virtual shanty sings at home remotely until this month. “It is a little unfortunate that this popularity comes in the middle of a pandemic, when no one can actually come together and do the real thing,” said Lambert.

Lambert, who says he’s had many articles around the “Wellerman” craze sent to him by friends, isn’t so sure that the craze is related to the pandemic. “I think it’s more a matter of this guy in Scotland putting his own spin on the song (which I had actually never heard), with a great hook that happened to resonate with a wide audience. And now, it’s great to see others who are continuing to make it their own.”