What will work be like in the future? Will people be replaced by artificially intelligent robots? If that happens, what kind of work will be left for people to do? And will universal basic income be necessary for survival?

The scariest part of these questions is not about potential trends in the future, but rather the thoroughly documented danger of what will happen if current trends merely continue. While there is a vast literature of economics papers published at least monthly for the past half-century, all pretty much in agreement, our society no longer bothers to notice.

Compensation Trends

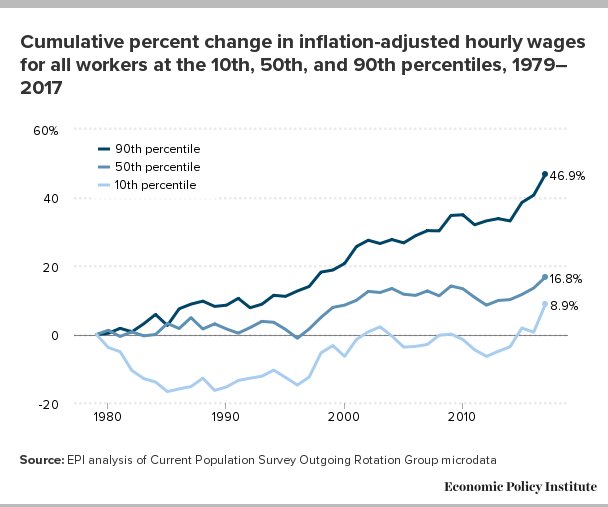

In 2018, John Schmitt, Elise Gould, and Josh Bivens of the Economics Policy Institute (EPI) published “America’s slow-motion wage crisis: Four decades of slow and unequal growth,” one of many such papers distinguished not by its data but by its unusually clear language of warning: “For the last four decades, the United States has been experiencing a slow-motion wage crisis. From the end of World War II [in 1945] through the late 1970s, the US economy generated rapid wage growth that was widely shared. Since 1979, however, average wage growth has decelerated sharply, with the biggest declines in wage growth at the bottom and the middle. The same pattern of slow and unequal growth continues in the ongoing recovery from the [2009] Great Recession.” Wage changes have been worse – even negative – for some, especially women, non-whites, and non-college graduates.

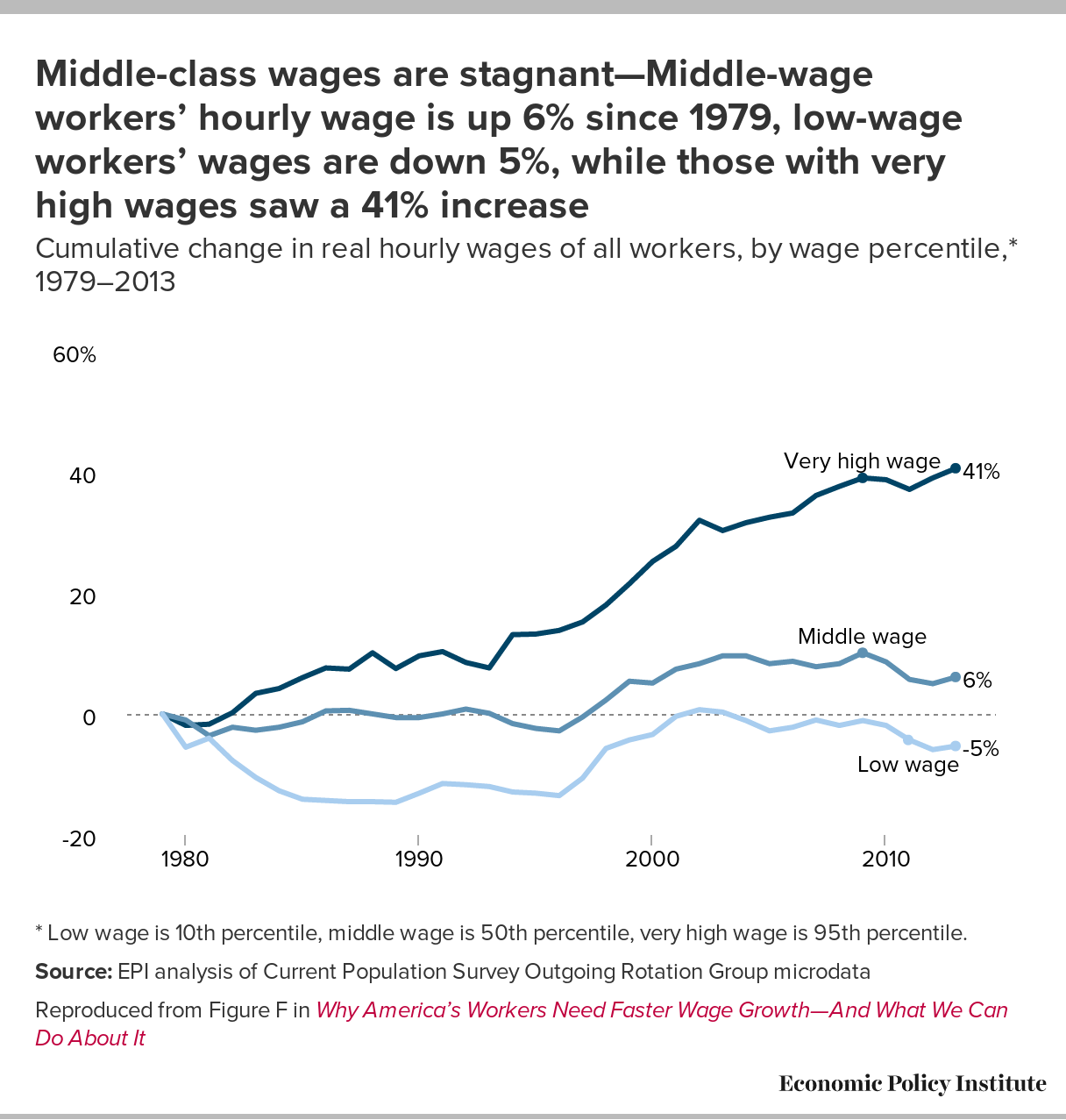

Three years earlier, in 2015, Lawrence Mishel, Elise Gould, and Josh Bivens of EPI published “Wage Stagnation in Nine Charts,” each labeled with such pithy summaries as “The US middle class had $17,867 less income in 2007 because of the growth of inequality since 1979,” “Middle-class wages are stagnant – Middle-wage workers’ hourly wage is up 6% since 1979, low-wage workers’ wages are down 5%, while those with very high wages saw a 41% increase,” “Wages of young college grads have been falling since 2000,” and “The minimum wage would be over $18 had it risen along with productivity.”

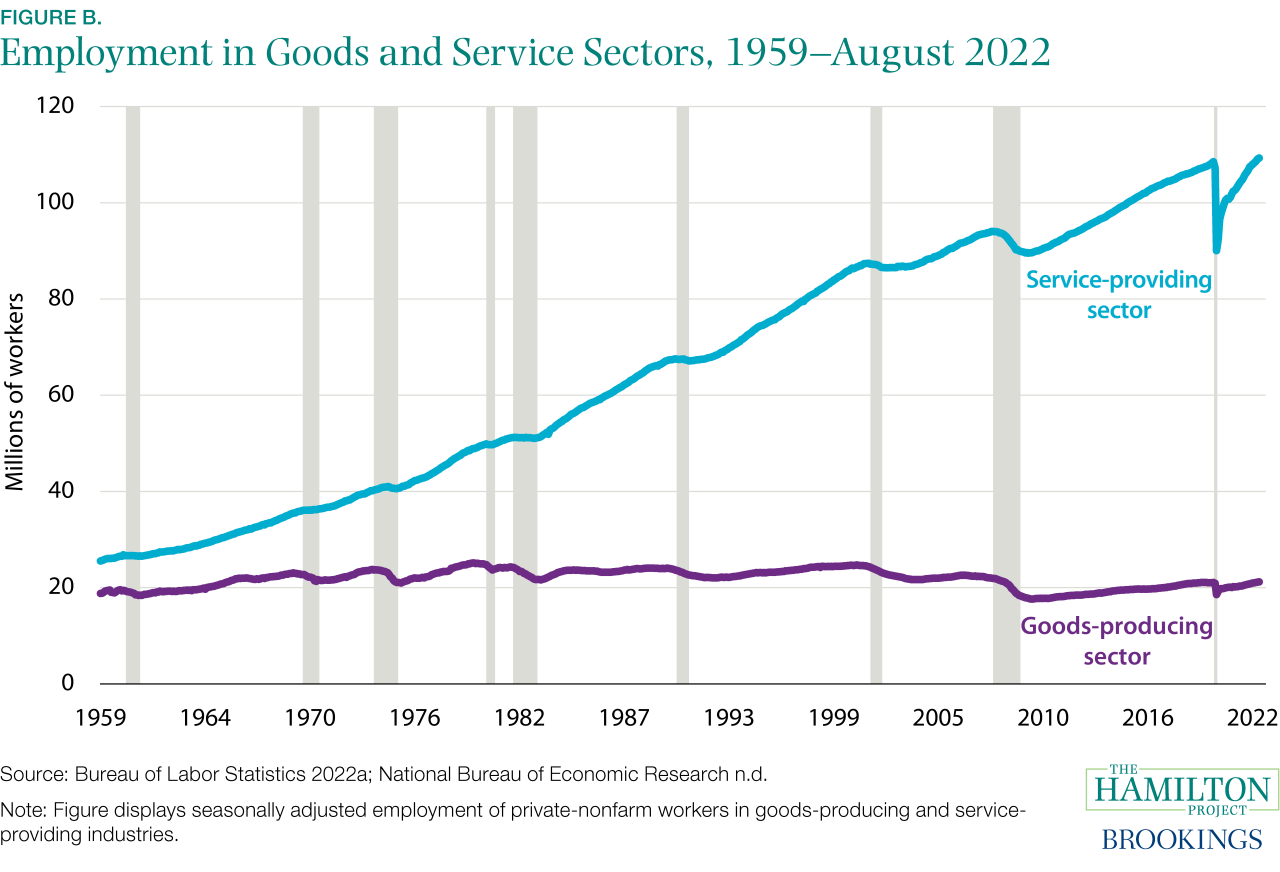

Why? One big factor is that the kinds of jobs Americans hold changed, as noted in 2020 in “Forty years of falling manufacturing employment” by Katelynn Harris of the US Bureau of Labor Statistics: “Despite being a leading driver of employment growth for decades, manufacturing has shed employment over the past 40 years as the US economy has shifted to service-providing industries. In June 1979, manufacturing employment reached an all-time peak of 19.6 million. In June 2019, employment was at 12.8 million, down 6.7 million or 35 percent from the all-time peak.”

The problem is not the expansion of the service sector: After all, we need doctors and nurses, grocery workers, and many other such jobs. The problem is the contraction of the manufacturing sector, explained Mitchell Barnes, Lauren Bauer, and Wendy Edelberg of the Hamilton Project at the Brookings Institution in “Nine facts about the service sector in the United States” in 2022.

“Is this bad? Of course not. The standard of living has clearly improved … Indeed, goods can now be produced with fewer people – thanks to technological progress and automation” wrote Christian Zimmerman in 2018 on the official blog of the St Louis Federal Reserve branch. But what happens to these workers as their jobs move offshore or are automated?

In 2017, I quoted then-Gov. Gina Raimondo explaining the RI Promise scholarship program: “When I was a kid, you could graduate from high school and get a good job with a good salary to support a family. But that’s not the case anymore. In Rhode Island, it’s estimated that by 2020, seven out of every 10 [new] jobs will require some kind of education beyond high school. But right now, less than 45% of Rhode Islanders have that.” While the optimistic view is that education can solve this, there is going to be an increasing share of the population who will become unemployable because jobs they once could have held will no longer exist. College is not for everyone, especially with its cost rising three times faster than inflation for the past 40 years; but we provide almost no alternative educational tracks.

Universal Basic Income

One idea is that we should abandon the centuries-old assumption that each individual must “earn” their living or be doomed to homelessness and starvation, and instead simply give every person enough cash to survive, a concept that has become known as “universal basic income.” There have been numerous political and economic attempts to test it, but only on small and limited scales, with inconclusive results confounded by external variables. The case for UBI has historical advocates, including Thomas Paine in the early United States (1797) and Joseph Charlier in Belgium (1848), and modern advocates across the traditional left-right political spectrum. In the 1930s, trade union advocates saw universal basic income as a remedy for grossly disproportionate bargaining power between capital and labor. In the 1960s, National Welfare Rights that united disparate factions in the civil rights movement, ranging from Martin Luther King, Jr, to the Black Panther Party, saw UBI as a direct solution to poverty regardless of race. In the 1970s, conservative economists such as Milton Friedman saw universal basic income, what he called a “negative income tax,” as a straightforward replacement for traditional welfare, eliminating all of the paternalistic rules that cost the government huge time and effort to apply. He reasoned that poor people would be highly motivated and best positioned to judge how to spend their allotment. Major economic organizations, notably the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund, have seen universal basic income as an effective way to address poverty. Democratic candidate Andrew Yang called UBI the “Freedom Dividend” and made it the centerpiece of his 2020 presidential campaign.

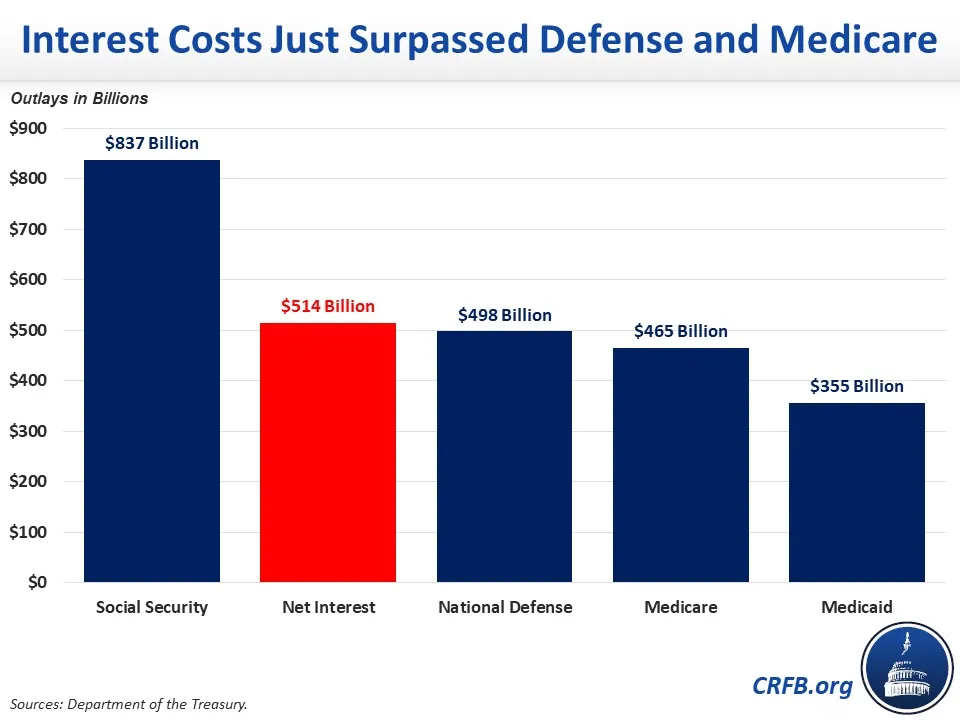

But can we afford it? The federal debt, the amount the government has borrowed on behalf of all of the people in the country, currently stands at $36.2 trillion and is increasing by $1 trillion about every 100 days. Most of the growth in debt has occurred in recent decades. As the US Treasury put it a few months ago comparing the gross domestic product, “The average GDP for fiscal year 2024 was $28.82 T, which was less than the U.S. debt of $35.46 T. This resulted in a Debt to GDP Ratio of 123 percent.” In May 2024, the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget reported that, for the first time, annualized interest payments on the debt ($514 billion) exceeded the cost of defense ($498 billion), Medicare ($465 billion), and Medicaid ($355 billion).

The Likely Future of Universal Basic Income

Worse, national policy has been going almost entirely the other way. As Chuck Marr, Samantha Jacoby, and George Fenton of the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities wrote in June (“The 2017 Trump Tax Law Was Skewed to the Rich, Expensive, and Failed to Deliver on Its Promises”), rather than trying to reduce poverty, tax cuts under Presidents George W. Bush and Donald J. Trump undermined the ability of the government to maintain revenue necessary to keep up with expenses: “In the three years immediately preceding the first Bush tax cuts, revenues averaged 19.5 percent of GDP, compared to 16.3 percent in the years immediately following the Trump tax cuts … according to [the Congressional Budget Office]. The revenue difference is stark: revenues in 2023, for example, would have been roughly $830 billion higher if they had totaled 19.5 percent of GDP as in the years before the Bush tax cuts.”

Former US Labor Secretary Robert Reich even predicts that the expanding debt will be exploited in a cynical political attempt to eliminate Social Security.

Motif contributor and college professor with degrees in economics and finance Maureen O’Gorman expressed the opinion to me as I was eating breakfast — I get all of my best punditry advice during breakfast — that the Baby Boomer generation has exceeded the willingness of any other to “eat its young.” That is exactly what is happening: the generation that has been electing octogenarian presidents has been borrowing profligately to give themselves tax cuts while sticking their children and grandchildren with the bill, not even stopping to worry about the profound changes likely in the next 20, 50, or even 100 years as jobs that cannot be automated become so demanding of cognitive skills and educational credentials that the average person will be unable to do them. The evidence is thin so far whether UBI will work as a solution, and it seems unlikely to be a reality in this country any time soon, but it deserves serious study and may be our best hope.