In 1925, while cyclists – with chattering teeth and shaking bones – raced ’round the pine-board planks of the nation’s largest velodrome, upwards of 13,000 fans roared from Providence’s East Side.

At one time, cycling was the most popular sport in the world. Indeed, at the same time robber barons were building their mansions on Bellevue Avenue, all across the globe folks were wild about the two-wheeled machine.

In 1879, the Providence Wheelmen were founded. Just a year later, Newport gave us the League of American Wheelmen. And a year before that, cyclist Marshall “Major” Taylor, the world’s first Black international sports superstar, was born.

Cycling fanaticism began with those silly, big-wheel bicycles. But with the advent of rubber tires and chain drives in the late 1880s, the modern bicycle (dubbed “safety bicycles”) absolutely exploded the cycling craze.

On May 31, 1880, Kirk Munroe and Charles Pratt founded the League of American Wheelmen in Newport, RI. The purpose of the League was to advocate for the growing number of bicyclists around the nation. They planned outings and casual gatherings – for Providence’s semiquincentennial in 1886, the League put together a parade of 1,500 cyclists down the roads of Rhode Island’s capital.

But they also engaged in political lobbying. One of the most famous achievements of the League was getting America’s roads paved. Before the nation’s cyclists banded together, most roads were either craggy mud trails or uneven confederacies of stones and trolley tracks. But by 1893, the League had pressured the federal government to open the Office of Road Inquiry, a precursor to the Federal Highway Administration.

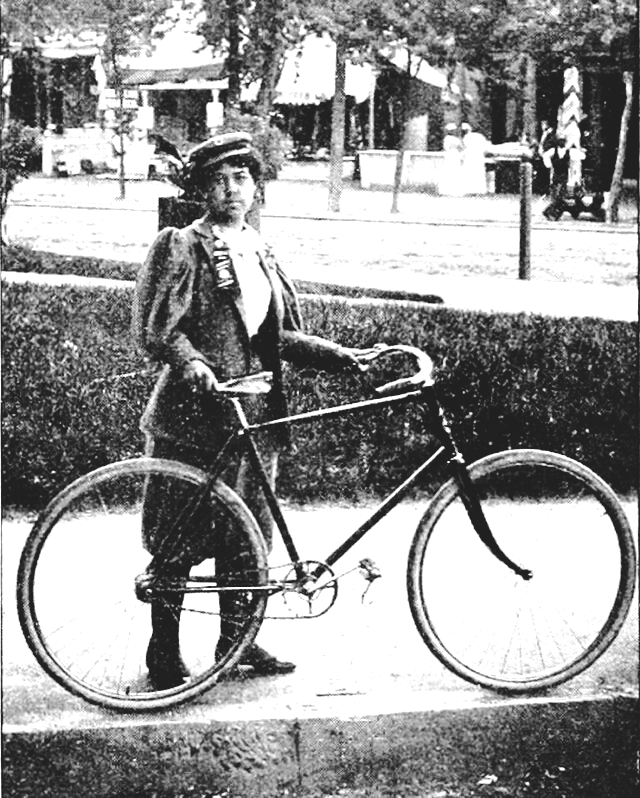

As roads improved, a rise in ridership followed. Bicyclists were mainly men, but women too saw the wheel as a tool of independence. Indeed, in 1894, Annie Londonderry – a Jewish Bostonian – became the first woman cyclist to circumnavigate the globe…on a dare! She began her tour only two hours after learning how to ride a bike and would rest after the first leg of her long journey, in Providence.

In reality, much of her story was vastly exaggerated, but that didn’t stop her from becoming international news. Annie certainly rode her bicycle on at least four continents for longer journeys than most will ever embark on in their lives. But she was also an excellent storyteller and knew how to excite public interest with tales of highwaymen, imprisonment, and communists.

Her story did wonders for women’s empowerment. And in 1896, Susan B. Anthony would say of the bicycle, “I think it has done more to emancipate women than anything else in the world. I stand and rejoice every time I see a woman ride by on a wheel.”

The gay ‘90s would reach the pinnacle of the bike-riding craze, but 1890 is also the decade of American history with the most recorded lynchings.

As Black cyclists grew in number, so too did anti-Negro sentiment within the League of American Wheelmen. And by 1894, the anti-Negro caucus finally convinced the League to bar Black cyclists.

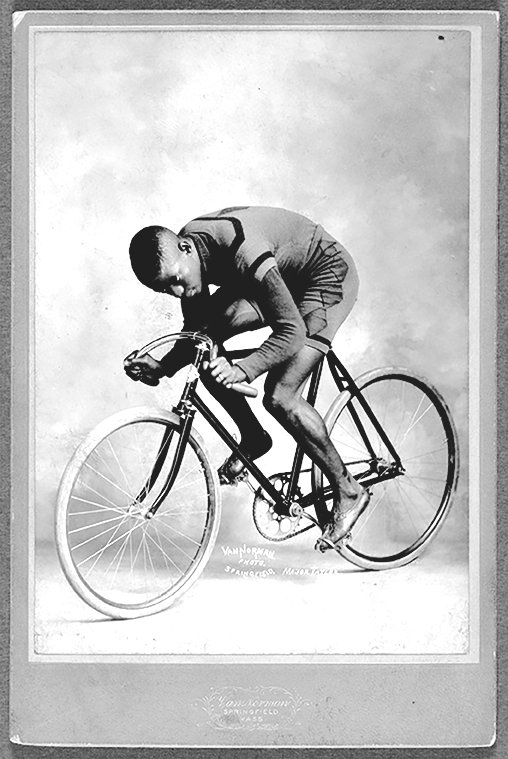

This was the culture in which the young, gifted, and Black Majorl Taylor became “the fastest bicycle rider in the world.” Born in Indianapolis, Major Taylor moved to Worcester, MA in 1895 to begin a career as a cyclist – competing on some of the first integrated teams in any sport in America.

Taylor would win early races at Providence’s Narragansett Park in 1896 and quickly became a globetrotting sensation. But that didn’t stop him from being chased around the track with a knife at one race or getting choked out after another. Still, by 1899, Taylor had broken multiple world records and would famously win the Montreal World Championship.

The League’s decision to bar Black cyclists was wildly unpopular. And although challenged by brave Black riders like Boston’s Kittie Knox, the League’s color-line was never officially repealed until, in 1999, Earl Jones made the League of American Wheelmen formally revoke its whites-only law.

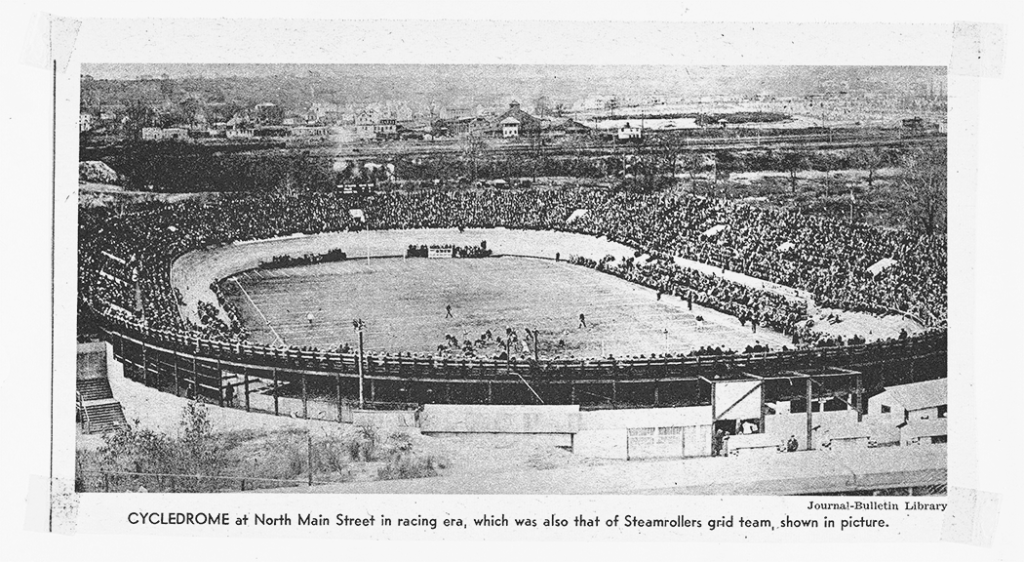

Before 1925, races in Providence were held at Narragansett Park. Cyclists would share the track with horses and motor-cars. When the Cranston track closed in 1924, Italian American entrepreneur Peter Laudati opened the Cyclodrome near the Pawtucket line. Technically it opened as the “Cycledrome” – as you can see in early signage – but “Cyclodrome” seems to flow from the tongue better, because later advertisements mostly preferred that spelling.

With a capacity of 13,000 spectators, the Cyclodrome was the largest bicycle track in the country when built – maybe even the world. For reference, that’s larger than Seekonk Speedway, which seats 10,000.

The Cyclodrome seemed to often feature Italian American riders, and even produced local stars like Vincent Madonna who raced on the track’s opening night.

And of course, the bike track was famously home to the NFL team, the Steamrollers, who would win a championship in 1928 and feature the NFL’s first Black player, Fritz Pollard – a Brown graduate.

Like many of his Black contemporaries, Major Taylor experienced the highest of human highs – and after retirement, the lowest of lows. Like Providence’s own Sissieretta Jones, who retired early from a career as a world-famous opera singer to take care of her sick mother, the record-breaking cyclist died of a heart attack at 53 and was buried in an unmarked grave until friends and family could gather the funds to give him a proper memorial.

Things end. But never forever.

Though the Providence Wheelmen are no more, they were reborn in 1971 and rechristened the “Narragansett Bay Wheelmen.” In 1937, the Cyclodrome was razed to make way for E. M. Loew’s Drive-In. And in 1977, the drive-in was torn down. Today, there’s an Ocean State Job Lot and a Chili’s where the Cyclodrome used to be. Though many Providence residents remain unaware of the city’s exciting history of cycling, our state’s role in cycling development has gone down in history.