“Hello? I just had a missed call from this number.” Shaena Soares calls me from her car. She just started driving for Uber. “I thought I had something to do today, let me pull over.” Soares apologizes and says her brain is scattered. “I’ve got five kids, two sets of twins and one in the middle.” In addition to driving for Uber, she makes jewelry and sells her artwork on commission. She also homeschools her kids. “ I wasn’t gonna allow my kids to keep learning about Christopher Columbus in school. So I decided to take them out and teach them myself. It takes a lot, but there are a lot of injustices that have been done, not just to the Native American people but to a lot of people who are Indigenous to their own parts of land. You know what I’m saying?”

Born and raised in Providence, a member of the Narragansett Tribe, and a lifelong doodler, Soares learned she could paint in high school.

“A lot of times I’d outlet through art, but it wasn’t until I was fifteen and went to The Met on Public Street and I came across somebody, his name was Sydney. He’s since passed, but was the driving force for me to take art seriously. He ran this art class after school; we started with acrylics, then we started doing airbrushing, a bunch of different things – pastels, charcoals, all that good stuff. Sydney was so encouraging; he said, ‘You can paint!’ And I was like, ‘I don’t really know how to do this and that.’ And he says, ‘No, you can really, really paint.’ So I started taking it seriously.”

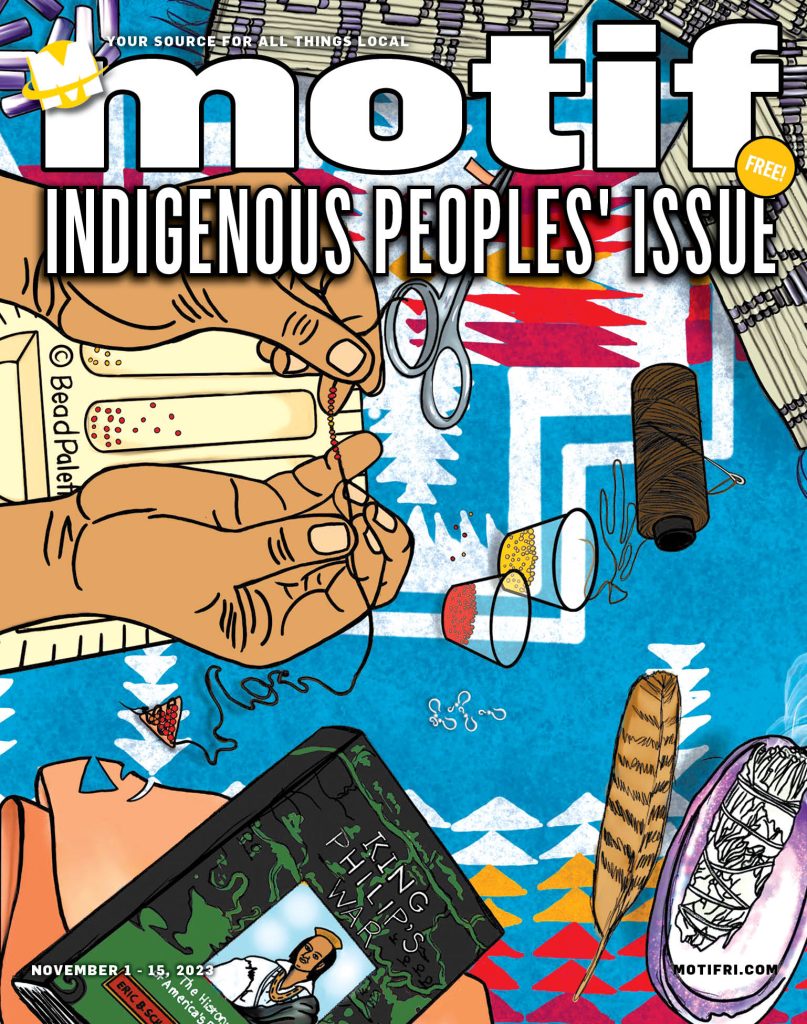

For this issue’s cover, Soares wanted to paint from the artist’s perspective, to show the viewer what she sees when creating, she calls it The Artist’s Eye. She shows us her desk covered by a traditional Native blanket; her bead palette with little cups of yellow and red beads, two colors of the Medicine Wheel — yellow for growth, red for the spiritual. We see her hands threading sinew through beads, the smudge stick she uses to balance the energy and begin her prayers, we see the wampum she holds the smudge stick in and a hawk feather to remind her of her sacredness. Along the top runs a wampum belt, at the bottom sits a copy of King Philip’s War: The History and Legacy of America’s Forgotten Conflict.

“I wanted to put the book in there because it is Native American Heritage Month and that book was taken out of a lot of school curriculums. More people should read it for the simple fact it brings to light what was going on at that time. Ancestrally, [Narragansetts] were part of King Philip’s War and it was something really huge in terms of how many of our people were lost. The fact they did what they did forced the hands of the Narragansetts because originally the Narragansetts did not want to be part of King Philip’s War. But when the settlers waged war on our lands, we were kind of forced into action to fight alongside Metacom.”

Soares refers to the Great Swamp Massacre, which has been described as “one of the most brutal and lopsided military encounters in New England’s history” (King Philip’s War: Civil War in New England, 1675–1676, James D. Drake) and yet many persist in calling it the Great Swamp Fight.

“It wasn’t a fight. It was a massacre — call a spade a spade. They came while the men were away and decided, ‘Okay, there’s no one but the sick, the elderly, and women and children, let’s do what we gotta do.’”

As a child, Soares used to have visions. Long before she knew of the Great Swamp Massacre, while driving with her family to powwow, she’d have visions of a massacre; she didn’t understand what they were and kept them to herself for fear of being called crazy.

“I should’ve been more willing to tell my mom, because she had dreams. And when I say my mom had dreams, I don’t mean my mom had dreams like the sky is falling. My mom had dreams that came to fruition.” When she was 17, Soares finally told her mom and learned her mom had them, too. “When I told her, she looked at my father, and he was like, ‘Isn’t that what you see?’”

Years later, Soares learned the location of the Great Swamp Massacre; it took place on the same stretch of land where she had her visions. She still doesn’t understand the purpose of the vision, but she still feels the outrage in her body.

“We are hundreds of years from the whole situation, and it’s still speaking to me. It didn’t physically happen to me, but it feels like it physically happened to me. I’m sure many people would say, ‘Well if we just took it out of the history books, then you would forget about it.’ And it’s like, no. Something doesn’t sit right energetically, it’s like you’re being lied to and you know you’re being lied to.”

In her mid-twenties, Soares was elected to the Narragansett tribal election committee, and every time she stepped foot on her reservation, she’d get sick.

“We had to sit in meetings once a week or so, and on my way home, I would get to a certain exit, and I would purge. I would come home every single time and, I would vomit. I never understood it.”

Recently, she had an epiphany: The ground needs a cleansing. “People may say, ‘You’re crying about spilled milk; you need to get over it. This is where we’re at now.’ I understand that. I try my best to pay homage to the injustices and I also try to be soft. I try to be balanced. I know that this is the world we live in, we live here, today. But like all things that make you sick, you must acknowledge the problem. I feel the unfortunate part of Rhode Island is we don’t always acknowledge the problem.”

To see and support Shaena Soares’ artwork, follow her on Instagram @wild_fire_creations_