It’s 1966, and the North Providence High School football team’s out on the field for practice. One of the players, Len Cabral, looks down at a grass stain on his uniform.

It’s 1966, and the North Providence High School football team’s out on the field for practice. One of the players, Len Cabral, looks down at a grass stain on his uniform.

“Out, damn’d spot! Out, I say!”

His teammates look at him.

“Which of you have done this? Thou canst not say I did it: never shake thy gory locks at me.”

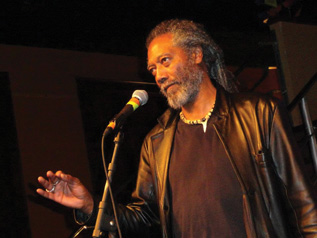

Before he became an internationally acclaimed storyteller, before a lifetime of traveling the globe, collecting and sharing its tales, Len Cabral was a Shakespeare-quoting football stud.

“I spent more time in the locker room than a library,“ says Cabral. But he was turned on to Shakespeare by an English teacher, and before long, had other teammates quoting Shakespeare on the field. Or he’d spout Bob Dylan songs, singing ‘‘How does it feel…?” to an opposing player while tackling them to the ground. “I had a lot of fun with language.”

Len Cabral was only beginning to find his voice. And often, it was a goofy one.

After high school, he went into the military. It wasn’t until he started working at a daycare in the early ‘70s that he began experimenting with storytelling in an attempt to keep the attention span of the very young children. Getting a sense for what he wanted to do, he attended Rhode Island College and took classes on theater, children’s literature, early childhood development, dance and mime. Knowing that the GI Bill wouldn’t pay for a full degree, when anyone bothered him about requirements or a specific class he was supposed to take, he’d just tell them, “Yeah, yeah, I’ll take it next year.”

Then, Providence Inner City Arts, an organization that Cabral was a part of and eventually president of, got a grant for two people to do creative dramatics in daycare centers in Providence. It was mostly theater at the time until about six or seven years later, when Cabral shifted his focus to storytelling and started traveling the country.

Forty years of storytelling later, and that focus is on FUNDA Fest, the annual storytelling festival put on by the Rhode Island Black Storytellers (RIBS). They have been performing at schools around the city all week, in addition to performances at various libraries and theaters. The festival has been going on for 18 years, and the Rhode Island Black Storytellers have been around even longer.

Because of the festival in late January, it’s a little bit busier of a day than usual, but not by much. After two high energy shows at the International Charter School, Cabral arrives at the next school early for his final show of the day. It is the end of the lunch break and Cabral is led to an auditorium turned cafeteria where he will be performing.

He walks in and the kids are sitting in strict rows of perfectly aligned beige tables. A man in a purple button-down stands at the center. He blows his whistle, referring to each table by its number. “Number 16” is told to proceed. They go single file to put down the trays from their pizza lunch, and when a soft murmur rises from this room of children, they threaten to take away their recess. “You want me to let you outside?” he hollers, in between shrieks of his whistle. Off to the side, another teacher pushes his chest out, raising his shoulders up and backwards at the child he is talking to, exerting himself.

He walks in and the kids are sitting in strict rows of perfectly aligned beige tables. A man in a purple button-down stands at the center. He blows his whistle, referring to each table by its number. “Number 16” is told to proceed. They go single file to put down the trays from their pizza lunch, and when a soft murmur rises from this room of children, they threaten to take away their recess. “You want me to let you outside?” he hollers, in between shrieks of his whistle. Off to the side, another teacher pushes his chest out, raising his shoulders up and backwards at the child he is talking to, exerting himself.

It’s a performance of power and intimidation, and Cabral is not impressed. At the first school, where he has been doing shows for ten years, he remembered the teachers, hugged them and stopped to chat. They showed off their students’ artwork. Now, he stands in the corner watching yet another, third man yell at a child for not sitting straight. For the first time in a busy day, Cabral loses his charismatic smile. In fact, he’s pissed off. “These kids should be having little conversations among themselves, telling stories,” he says. He explains that at schools like this, the kids look at him like he’s Santa Claus. “I’m not going to be another adult who is condescending to kids,” he said earlier in the day.

Cabral knows that telling stories is not a neutral act. “I got more concerned about having a story that has something to say.” he explains. “There’s so many things that make us disconnected in society … [Stories] help us with empathy and compassion.” So he makes an effort to find stories with female heroes, with elderly heroes, and tells stories from around the world, creating the opportunity for students to see themselves in the tale, or challenge a stereotype. “I try to find the right story for the right audience.”

Sometimes, when he gets to a school, especially all white schools, he goes straight to the library and sits on the ground, reading books. He knows that the kids are watching him, and wants them to see and hear things that will make them question assumptions they’ve learned from the media or their parents.

This school, however, is mostly students of color, and when they finally exit the lunch room, a new bout of power struggles occur as the fifth grade class enters. Once they’re seated, Cabral launches into his first story, a crowd favorite: “Old Man Winter.”

As he speaks, he gets a couple restrained giggles, so he goes bigger. A couple more laughs? The voice gets sillier and louder and his body starts stretching across the space in exaggerated movements.

If they’re getting restless he sits down, starts speaking more softly.

In between stories he does a variety of activities, from repeat-after-me activities, to poems, songs and jokes. In the morning, he started humming ever so quietly, and it was only a couple moments before the kids stopped talking and started humming with him, and then singing. He uses these more off-handed moments between stories to teach small tidbits about nutrition, or encourage the students to learn their parents’ or grandparents’ languages, if they haven’t already.

With this older and decidedly more cynical group, he decides to talk to them.

“I might be in the room right now with someone who will discover the cure for cancer. Or clean the atmosphere. Or write a book. I hope you have your sights set high.”

And like that, the room is silent. The young girl who, not long before, was rolling her eyes, whispering “This is weird,” to her friend isn’t saying a thing.

Cabral later admits that once, after a similar speech, a high school student almost made him cry. She approached him after the show to thank him, to tell him that no one has ever told her that before — that she could amount to something.

Who knows what this group will walk away thinking. Perhaps they will talk about Cabral’s stories to their parents, or remember one of his stories years later. At the very least, for 50 minutes these children were not being yelled at. They were not being physically intimidated by large men, not having whistles blown at them. Instead they were laughing and being told that they could do anything. They were dreaming of other places, other worlds.

Once the show was over and the kids rushed outside to go home, Cabral sighed.

“They were in need of a story.”

Len is top flight, a real Rhode Island treasurer!!!!