The four-story brick building has been a fixture between Allens Avenue and the Providence waterfront since 1899. Patrick Conley bought the turn-of-the-century building more than a decade ago, and later envisioned Conley’s Wharf as part of a plan to transform the north end of the waterfront into a mixed use area with restaurants, hotels and residences.

The four-story brick building has been a fixture between Allens Avenue and the Providence waterfront since 1899. Patrick Conley bought the turn-of-the-century building more than a decade ago, and later envisioned Conley’s Wharf as part of a plan to transform the north end of the waterfront into a mixed use area with restaurants, hotels and residences.

Conley’s company, Providence Piers, invested $7 million to transform the building, including a spacious fourth-floor meeting room overlooking the Providence River.

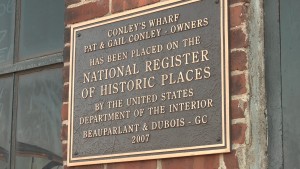

When it was finished, the building, which received state and federal tax credits, went on the National Register of Historic Places and began to attract tenants. But in late 2011, Sims Metal Management bought land adjacent to Conley’s property and began stockpiling scrap metal.

When it was finished, the building, which received state and federal tax credits, went on the National Register of Historic Places and began to attract tenants. But in late 2011, Sims Metal Management bought land adjacent to Conley’s property and began stockpiling scrap metal.

It’s a familiar sight to anyone travelling on Route 95 north the past five years: a scrap heap that sometimes rises as high as the four-story building next to it.

“They actually closed (on the sale) and dumped their scrap right on the land itself, without even putting down a concrete pad, which they’ve done since,” Conley said.”They just dumped the scrap in October, November of 2011 and they built the scrap pile initially up to a height of almost 80 feet. Millions of tons of scrap.”

And that, Conley said, had an immediate effect on his building. “All of the sudden cracks started to appear throughout those additions, totaling 8,000 or 9,000 square feet, to the point where they had to be vacated because they were unsafe. Because that area could collapse at any minute because the cracks are an inch or two wide and getting wider all of the time.”

And that, Conley said, had an immediate effect on his building. “All of the sudden cracks started to appear throughout those additions, totaling 8,000 or 9,000 square feet, to the point where they had to be vacated because they were unsafe. Because that area could collapse at any minute because the cracks are an inch or two wide and getting wider all of the time.”

Providence Piers filed a lawsuit in U.S. District Court in Providence, seeking injunctions to stop Sims, all of which were denied. Sims maintains that it is not responsible for any of the damage and that Conley’s building was settling anyway. And the company’s attorney refused to speak with us about the case.

The situation has also caused an exodus at 200 Allens Avenue. “And because of the arrival of Sims, the damages that were caused, particularly the lower level of the building where many of the artists’ studios were located, toxic emissions, particulate matter from the scrap pile, they decided not to renew their lease,” Conley said. “So we lost our main tenant. And then some of the other tenants moved out as well.”

The situation has also caused an exodus at 200 Allens Avenue. “And because of the arrival of Sims, the damages that were caused, particularly the lower level of the building where many of the artists’ studios were located, toxic emissions, particulate matter from the scrap pile, they decided not to renew their lease,” Conley said. “So we lost our main tenant. And then some of the other tenants moved out as well.”

Conley says Rhode Island’s Departments of Transportation and Environmental Management have both dropped the ball. DOT, he says, is ignoring a law that regulates junkyards within 1,000 feet of a federal highway, such as Route 95.

“We were able to preserve it, make it economically viable and place it on the National Register,” Conley said. “So it’s an historic site. And yet, the state has shown no interest whatsoever in protecting[it]. If you went up to Benefit Street or somewhere else and started trashing an historic property, there’d be an outrage. This is an historic property, no one cares.’’

Conley says he’s simply asking for his day in court, but understands why the defendants don’t want to see the case go to a jury. “There will be a verdict in our favor for damages. They’ve caused damages — it’s incontrovertible that the building has been damaged in some way and to some amount by the activities of Sims. It will be up to a jury, guided by the judge, of course, to make a determination of the extent of the damages. We certainly would want to bring the jury over for a view, for a visit, and walk them through that building to make their own decision as to whether these millions of tons of steel within 100 feet of this building could have caused the damages that they will witness.”

Conley says he’s simply asking for his day in court, but understands why the defendants don’t want to see the case go to a jury. “There will be a verdict in our favor for damages. They’ve caused damages — it’s incontrovertible that the building has been damaged in some way and to some amount by the activities of Sims. It will be up to a jury, guided by the judge, of course, to make a determination of the extent of the damages. We certainly would want to bring the jury over for a view, for a visit, and walk them through that building to make their own decision as to whether these millions of tons of steel within 100 feet of this building could have caused the damages that they will witness.”

The Hummel Report is a 501 3C non-profit organization that relies, in part, on your donations. If you have a story idea or want make a donation go to HummelReport.org, where you can also see the video version of this story. You can mail Jim directly at Jim@HummelReport.org.