When society experiences a monumental shift in social consciousness, citizens of that society must pause to fully appreciate and understand the gravity of what just occurred. Mayor Elorza and subsequently, Governor Raimondo, were correct in removing the word Plantations from the state’s name on official documents. Plantation is a word engulfed in the cruelty of imperial history, and the associations with Black slavery are loud, clear and irrefutable. But even then, in a state that once saw more than 100,000 enslaved Africans come through our ports, the word Plantation still manages to conceal further cruel secrets that eventually merge paths with the greater trans-Atlantic slave trade.

In the 17th century, the word plantation referred to the ‘planting’ of voluntary immigrants in foreign colonies. It was a practice famously imposed, and mercilessly perfected, upon the Irish during the Ulster and Munster Plantations of the early 1600s. The intention was to claim lands not your own, and place upon them the race, religion and political belief system of the colonizing force, ultimately making that location homogenous with the outsiders – total cultural erasure. With actions come consequences, and the consequences of British Plantations was the cultural disintegration and genocide of those peoples who were being planted upon. The same can be said of the experiences of the Indigenous communities of Rhode Island.

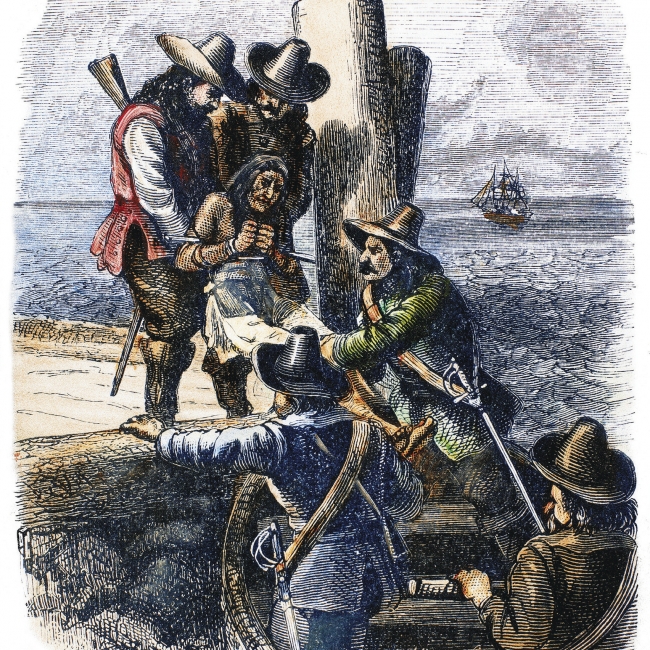

In 1600, what we now know as the Ocean State was home to the Narragansett people. Theirs was a life based around the seasonal movements of the forest, the rivers and the ocean, and upon the fields they planted with corn, squash and beans. Their world was part of an extensive interconnected society of Indigenous cultures stretching across the continent, an incredible network of thinkers, artists and pioneering agriculturalists. Few in that system had any real working knowledge of, or interest in, the intricacies of European religious discontent or their designs on colonization through settler plantations. When those European settlers came across the ocean and landed on the shores of North America, their single-minded intentions driven by religious zealotry and Eurocentric self-belief very much failed to take into consideration of those who already lived here. Roger Williams — whose letters show his request for an enslaved Indigenous child and whose son oversaw Indigenous slave auctions in Newport — may indeed have consulted with those people upon whose land he was settling, but that in itself was boldly presumptuous. It is not like Williams and the Narragansett had a pre-arranged agreement inviting colonists to plant themselves on Indigenous land.

Strong Indigenous leadership under Canonicus ensured that the Narragansett at least had peaceful relations with their parasitic neighbors, but the nature of a parasite is that it grows and behaves like a cancer. By 1675, the number of colonists had increased dramatically, and the locals found themselves increasingly pushed to the west, their vacant lands seized by the planters. With that came inter-tribal conflict as cultures encroached upon existing homelands, leading to even further Indigenous deaths. King Philip’s War of 1676 was the last – if desperate – throw of the dice for the region’s Indigenous inhabitants. Eight hundred colonists perished, but so did 3,000 Native people. Of those who remained, a mere handful escaped to join other tribes. The rest were sold into slavery.

That word again. Slavery.

Rhode Island’s past is blighted by the enslavement of people, both Indigenous as well as African. The first were those who had already endured extensive trauma in the form of land theft and genocide, and all were victims of the planters of the British Plantations.

So, what of Elorza’s and Raimondo’s decision? Removing the word Plantation from the state’s official documents is unquestionably the right thing. But doing so without also acknowledging the trauma endured by enslaved Indigenous people from the inception of the colony only serves to erase the Indigenous voice. Make no mistake — Rhode Island’s Indigenous people stand in solidarity with the Black community; this is by no means a diminishing of their suffering. But by changing the narrative, however good and honorable the intention may be, without including the Indigenous voice only serves to continue the age-old American narrative of sweeping that voice under the rug.