(Source: Facebook “Gothshooter Santana III” believed to be Jack Doherty, Jan 1, 2020)

A shooting on New Year’s Day that resulted in the death of Cheryl Smith, 54, at her home at 100 Baxter St, Pawtucket, has led to felony charges for murder in the first degree and conspiracy against Jack Doherty, 23, and Shaylyn Moran, 18. While homicides are uncommon in Rhode Island and extremely rare in Pawtucket, this one stood out even more because of reports that a firearm seized by the police in the course of arresting Doherty, the possible murder weapon, was 3D-printed. If so, this case would then appear to become the first known incident of a 3D-printed firearm being used in a homicide.

What is a “3D-printed firearm?” Using a computer file that describes the shape of a three-dimensional object, a 3D printer follows the instructions in the file to build up, layer by layer, a copy of the object described, from plastic polymer in less expensive printers up to metal in industrial-grade printers. An enormously wide variety of objects can be fabricated this way, from simple children’s toys up to custom-fitted prosthetic body parts — to, conceivably, parts for a firearm. The technology of 3D printing has revolutionized manufacturing and rapid prototyping, and the cost of a 3D printer has dropped in recent years to only a few hundred dollars. Many public libraries offer the use of 3D printers for a small fee.

While The Boston Globe (“Couple charged with killing mother in Pawtucket with 3D-printed gun”, by Amanda Milkovits, updated Jan 2, 2020, 3:11 pm) and The Providence Journal (“Pawtucket teen, N.Y. fiancé face murder charges”, by Mark Reynolds, posted Jan 2, 2020, 8:45am, updated Jan 2, 2020, 9:31pm) unequivocally state that the firearm used in the Pawtucket shooting was 3D-printed, investigation by Motif casts serious doubt on that.

(Source: Facebook “Gothshooter Santana III” believed to be Jack Doherty, Dec 22, 2019)

In response to our inquiry, Detective Sergeant Christopher LeFort of the Pawtucket Police Department Major Crimes Unit told Motif in an e-mail message, “As to the firearm, further examination and testing will be conducted to determine if in fact it is a 3D-printed firearm or some other make-at-home kit.” We located what we believe to be the Facebook accounts of the two defendants, both of which are still active as of this writing, with Doherty using the alias “Gothshooter Santana III” and Moran using the alias “Griselda Blanco.” We showed LeFort a photo from Doherty’s Facebook page, posted on Dec 22, of a handgun; he carefully replied, “The firearm found and seized from Doherty is similar in appearance and color as the one shown in the photo.”

(Source: Facebook “Gothshooter Santana III” believed to be Jack Doherty, Dec 11, 2019)

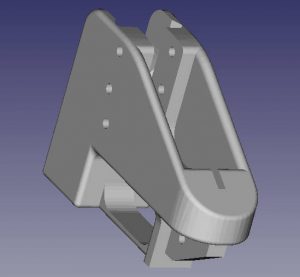

James Archer, a RI-based expert on firearms and the law, although carefully disclaiming that “my opinion is based solely on examining the pictures” and that “I may have a different opinion if I could examine it in person,” said “If the implication is that the gun was printed on a hobby [plastic] printer, then much of it could not have been. Also, 3D-printed guns typically work for a few shots and then fall apart. Assuming it’s true that the gun was somehow manufactured by its owner, it was more likely made from a kit…” Archer noted from the photos that the barrel is metal, not plastic, and “engraved with the caliber. No one is going to do that with a 3D printer.” He also noted that the slide was made from metal that had “blueing” worn off forward of the ejection port, and that the trigger had a safety lever that no one would bother to include with a 3D-printed firearm. “The receiver is plastic but that’s not uncommon in a commercial firearm. There is an extra hole above the takedown pin that’s badly drilled. There is a metal pivot pin and a metal takedown catch. The accessory rail is too perfect to be 3D-printed and in fact the stipling on the grip is too nice for a hobbyist 3D printer. I wish I had a pic under the rail where the serial number would be. That would probably answer the question. The kit guns have the indent where a serial number would go, but it’s blank. A 3D-printed gun would not have that.” Archer also pointed out that Doherty in a different Facebook post showing what seems to be the same gun wrote on Dec 11, “i made it today i had the day off,” a time frame inconsistent with 3D-printing a handgun, which would take significantly longer to print.

Under US federal law, per the Gun Control Act (GCA) of 1968, the “receiver” or frame is the only regulated part of a firearm, and unfinished receivers can be sold freely without restriction as kits for individuals to assemble their own firearms. According to the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives (ATF) web site, “Receiver blanks that do not meet the definition of a ‘firearm’ are not subject to regulation under the GCA. The ATF has long held that items such as receiver blanks, ‘castings’ or ‘machined bodies’ in which the fire-control cavity area is completely solid and un-machined have not reached the ‘stage of manufacture’ which would result in the classification of a firearm per the GCA.” It is possible for computerized machine tools to finish or substantially finish an unfinished receiver, but this is very different from 3D printing.

Considerable panic has surrounded 3D-printed firearms. Josh Blackman, now Associate Professor at the South Texas College of Law in Houston, in his 2014 Tennessee Law Review article “The 1st Amendment, 2nd Amendment, and 3D Printed Guns,” writes that so-called improvised low-tech “zip guns” have been around for many years, and he describes a YouTube video that “shows an improvised shotgun, which consists of two pieces of walled tubing, a nail, and a shotgun shell. It cost $7 of materials and took little time to make. It is quite lethal, and will likely not set off a metal-detector. While the notion of the homemade gun may make many uncomfortable, especially those unfamiliar with guns, this is not new technology.” Blackman argues, “The right to make arms for personal use, more so than commercial manufacturing, historically has been subject to virtually no regulations. It is deeply rooted in our nation’s history and traditions. The Second Amendment… protects three guarantees: the right to keep and bear arms, the right to acquire arms (for both the buyer and seller), and the right to make arms.”

Blackman cites the example of the “Liberator,” a one-shot handgun designed to be 3D-printed, the plans for which were posted on the web in 2013. Within three days, the US State Department ordered the plans taken down, saying the computer files were “arms” subject to export controls. However, as Blackman argues, “If Congress banned a book discussing how to build a handgun, which includes detailed blueprints and schematics of how the pieces should be assembled, it would be facially unconstitutional as a content-based prior restraint of speech. But what if Congress prohibited the same information, except rather than being printed on paper, it is shared in a digital format? This approach — how some propose stopping 3D guns — would similarly violate the freedom of speech.” But 3D-printed guns are not the purview of criminals, who have much easier paths to obtaining illegal handguns than investing a hundred hours and $10,000 to make one on a 3D printer, including all of the time needed for skilled hand-finishing.

Compared to 3D-printed firearms, kit firearms are far easier to obtain, although they are typically still more expensive than illegal street handguns. The facts are not yet known about the Pawtucket shooting, but our investigation, although admittedly based upon Facebook photos and other limited information, makes it very unlikely that initial reports are accurate that the firearm used was 3D-printed, although it is possible that part of it, such as the receiver, was finished from a kit by the defendant.