[Because of the length of this review, this is the first of two parts: the first part provides an overview of the production and the second part provides some additional detailed historical analysis of the script.]

Judaism is ultimately about lineage: Every Jew stands at the current endpoint of more than 3,000 years of history, and almost nothing else still present in the modern world reaches so far back. Judaism is so ancient that it is defined by geography and kinship, antedating concepts of what would later seem indispensable to the worldview of modernity, such as race, ethnicity or nationality.

The word “genocide” was coined by international lawyer Raphael Lemkin, the principal advocate for the postwar Genocide Convention of 1948, to describe what Nazi Germany had done in Europe beyond murdering not only individual Jews, even by the millions, but the further attempt to annihilate the existence of the entire Jewish people: “The objectives of such a plan would be the disintegration of the political and social institutions, of culture, language, national feelings, religion and the economic existence of national groups, and the destruction of the personal security, liberty, health, dignity and even the lives of the individuals belonging to such groups.” The Nazis wanted to wipe out all traces of Judaism itself: The extermination of Jews, their children and their children’s children was a means to that end.

Before Kristallnacht in November 1938, it was possible for the Jews of Germany to believe Nazism was a political aberration that in time would pass and allow life to return to normal, but afterward even the most assimilated Jews realized that they needed to get out of Germany at the risk of their lives, although by then it was too late. The British government, despite a track record of obstructionism in Mandatory Palestine and at the Évian Conference, were persuaded a few days after Kristallnacht to accept children up to age 17 as temporary refugees, but only children who as a condition of entry were forced to separate from their parents and lodge with British foster families who volunteered for the purpose. Between December 1938 and the beginning of World War II in September 1939, about 10,000 children, nearly all Jewish, were sent to safety in Britain via the Kindertransport – “child transport” – and as a result survived what otherwise would have been almost certain death in Nazi extermination camps.

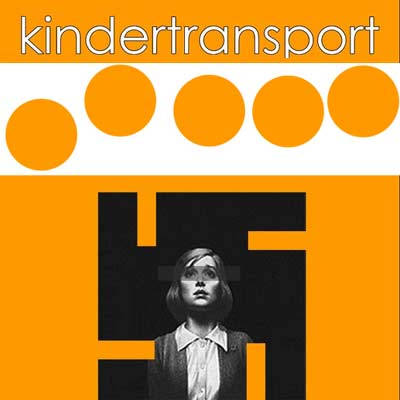

In this Your Theatre Inc. production, on stage right in the 1930s, 8-year-old Eva (Sabrina Guilbeault) is sent by her mother Helga (Margo Wilson-Ruggiero) to England as part of the Kindertransport, where Lil (Lucy Bly) becomes her foster mother; on stage left in the 1980s, Evelyn (Michele DeMary) is going through storage boxes with her college-age daughter Faith (Stephanie LeBlanc). The cast is all-female except for James Sanguinetti who plays a series of small roles: Rat-catcher, Nazi Border Officer, English Organizer, Postman, Station Guard. The two halves of the set are dressed with period furniture, emphasizing the half-century dividing them.

The cast does a very good job: Bly and Guilbeault are outstanding, and Wilson-Ruggiero is noteworthy. Bly is the only actor who regularly crosses between the halves of the stage representing a separation of 40 to 50 years, and the character is essentially the unchanging constant amid the chaos of war. Guilbeault effectively portrays a character who grows from an 8-year-old little girl with a thick German accent to a 16-year-old young woman whose English accent sounds as if she is a native of Manchester. Wilson-Ruggiero alternates between suppression and outpouring of emotion as she experiences, more than any other character, the horror of war.

It is not possible to properly review the play Kindertransport by Diane Samuels without introducing what might be considered “spoilers,” revealing what the audience is expected to figure out in the course of watching a performance. If you do not want to know these plot elements, then stop reading this review now.

The crux of the play is that Evelyn is Eva grown-up and Lil adopted her after the war, facts kept hidden from Faith until she discovers old papers, including letters from Helga. Just as Eva with the help of Lil was able to obtain the necessary paperwork to bring her parents Helga and Werner to England, the war began and shut down any hope of rescue. Lil, whom Faith knows as her grandmother, counsels her to forget the whole matter because it is painful to Evelyn to remind her of it. This is melodramatic and not skillfully handled by the script, but it is forgivable and probably occurred sometimes in real life.

Where the play begins to go off the rails is that Eva completely adopts a new identity as Evelyn, converting to Christianity at age 18 in the course of suppressing her prior identity as Eva. Where the play really goes off the rails is Evelyn’s revelation when confronted by Faith that her parents were sent to Auschwitz, and although her father Werner was quickly gassed to death, her mother Helga survived – a fact Evelyn concealed from Lil, who adopted her when both mistakenly believed Helga was dead. In a scene after the war, Helga comes to London to reclaim Eva and take her to New York, but Eva, 16 years old, tells Helga that England is her home and Lil is her new mother. Heartbroken, Helga leaves for New York and they never see each other again, Eva/Evelyn never even telling Helga of the birth of her daughter Faith.

Among the papers Faith finds are two books sent by Helga to Eva, one a children’s book about the Rattenfänger von Hameln (“Rat-Catcher of Hamelin”) and the other a Passover Haggadah, both heavy-handed symbols. The rat-catcher folktale is about all of the children of a city being stolen, a tragic circumstance that rips the heart out of the community. Passover is the central, defining story of the Jewish experience, the miraculous escape of the Jews from slavery and oppression in Egypt, but Evelyn cannot even remember what it is about when explaining to Faith that the book is for “some festival.” The Hebrew word “haggadah” literally translates as “telling,” because the purpose of the Passover festival is to fulfill the commandment (Exodus 13:8) for parents to tell the story to their children as if it personally happened to them “because of that which the Lord did unto me when I came forth out of Egypt.”

The play is problematic and, in my opinion, borderline offensive in portraying Evelyn as making a conscious decision to reject her Jewish ancestry and heritage, denying it to her own daughter Faith who explicitly says to her, “I should have been Jewish.” (Strictly speaking, under Jewish law, Faith is Jewish and could choose to embrace that identity.) While it is understandable from a psychological perspective why an individual might want to forget and suppress her past, by doing so she is aiding and abetting the genocide begun by Hitler and the Nazis, terminating her own lineage after three millennia, an act of cultural suicide. Despite hints here and there, the play utterly fails to confront the profound implications of that.

Kindertransport, by Diane Samuels, directed by Edward J. Maguire, performed by Your Theatre, Inc. (YTI), 136 Rivet St, New Bedford, Mass. About 2h15m including one intermission. Through Mar 24. Free off-street parking (entrance from County St). Refreshments available. Handicap accessible. Tel: 508-993-0772 E-mail: boxoffice@yourtheatre.org Web: yourtheatre.org/yti/index.php?page=event&evtid=253 Facebook: facebook.com/events/2578387565511357

Warning: The directions on the theater web page (which are the same as what you get from Google Maps) cannot be followed because of construction closure of the Rivet St exit from JFK Memorial Hwy (MA-18), so coming southbound from the north it is necessary to take the subsequent exit onto Cove St, then turn right onto County St northbound.

More Posts by The Author:

Heavy Rain, High Winds, Flooding Wed–Thu: Advisory for wind, watches for inland and coastal flooding posted

River Flood Warnings in RI, MA, CT: Wed through Fri, streets may be impassable at times

Snow possible but unlikely Sat mid-day: Little accumulation likely

Snow Thu Night: One inch expected

Significant Snow Storm Tue 5am – 3pm: Likely 6in but remote possibility up to 18in