On the desk sits a pile of paper, neatly disorganized. The blinds are open halfway to let the dusty morning light filter in. Outside, the vacant field is bright under a cold, blue sky. A woman enters her classroom, she pulls the blinds open all the way, sits at the desk, and begins grading. There’s a brief silence, she enjoys the gentle stillness between time.

When the school bell rings, all hell will break loose. But for now, the morning is hers. She marks papers, an experienced, swift slide of pen across silk. As quickly as the air settles, it is disrupted — an oil tanker pulls up outside her window causing a cacophony of beeping, swearing, and door closing. DelSesto Middle School in Providence, at one time, was struck by lightning, and all the power in the building went out. So outside the room of Kaleen O’Leary, a teacher frequently voted “teacher of the month,” is a generator, which must be filled with oil every morning. As the oil thumps into the generator, she stares at her pink brick wall, searching for answers, searching for humor in daily bouts of insanity.

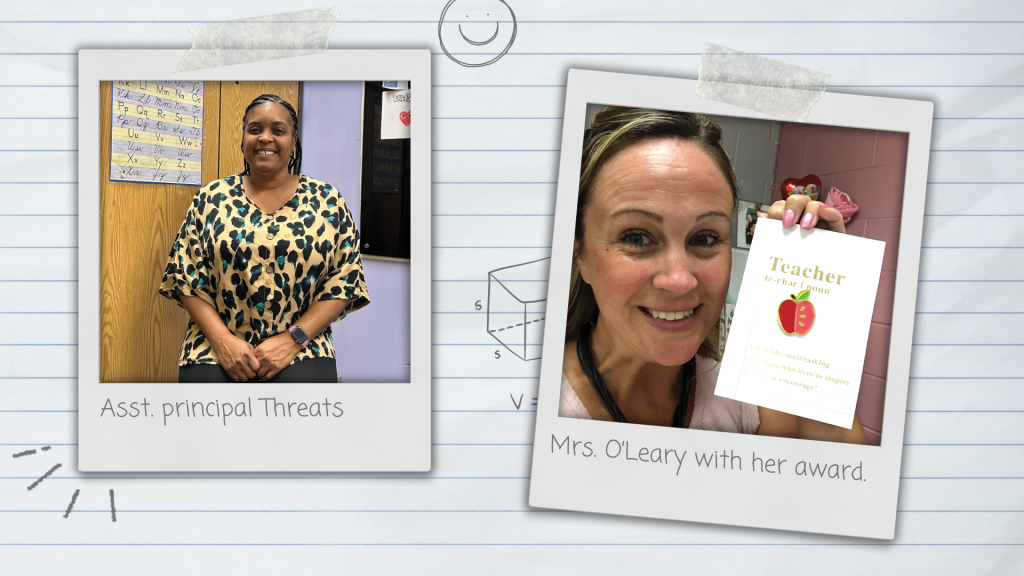

While O’Leary is preparing for the day, Kyisha Threats, the assistant principal of Delsesto, is outside in the middle of the hallway. She is directing kids, sometimes moderately pissed off, other times laughing along. Armed with a walkie-talkie that’s constantly buzzing her name, Threats spends her day on the phone with parents and caregivers, making sure the kids stay out of trouble and in their classrooms. She approaches each kid with a strong, tough-love approach: “It’s the love that makes you grow as an individual.” Being a teacher is more than just showing up to work, it is showing up in the lives of others.

O’Leary grew up in a family of teachers. Her mother, father, grandfather, and grandmother all worked in education; it goes so far back that her grandmother worked in the Providence school system when women couldn’t get hired if they were married. Her future was set very early on. She used to play school when she was a kid and, after graduating high school, went right into school to be a teacher. Threats followed a similar trajectory, “I always knew when I was young, I wanted to be a teacher, we played school all the time and if I wasn’t the teacher I wouldn’t play.”

Threats, who became a single mom in 1994 (right before graduating high school), made the decision to teach. Her career success is an inspiration to other young mothers. She reflects, “The kids I work with know my story; my life is not a secret to them… There are teenage girls who have babies, and it’s good to have this person who can push them along and say they can do it.”

O’Leary and Threats are essential members of DelSesto Middle School. O’Leary has taught at the school for 20 years and is the teacher that stays until dark working, runs a winter donation drive that collects items for the whole year, and helps score the girls basketball team, among many other acts of daily generosity.

I share a classroom next to O’Leary, and see kids running up to hug her, leaving her thank you notes, or trying to eat lunch with her. She is one of those teachers that believes in every single kid, and every single dream. Threats remembers coming into work as a teacher’s assistant, and meeting O’Leary. “She was on one end of the school and I was on the other. I was working with great teachers like her, who allowed me to become part of the classroom, who continue to build and support you.”

The Providence School System was taken over by the state in 2019, because, according to a report made by John Hopkins University, it was a “toxic environment for staff and students, and had perpetually low academic performance.” It is set to be given back to the local level in 2025, although O’Leary has some reservations. “How would I describe the school system? Taken over. Under redesign. Less autonomy. More micromanaged. Over the years it used to be ‘here’s the curriculum, teach it how you want.’ But now it is very regimented.” On top of a very strict curriculum that doesn’t allow teachers to create an environment of learning that fosters original growth and creativity, it’s hard to find, and keep, anyone to teach. Keeping teachers is difficult because of the varying degrees of hostility, and lack of management, in the classrooms. There are behavioral issues that often spiral out of control, and are not remedied, because kids aren’t being held accountable. O’Leary makes it evident that “as a teacher you have very little power. The majority of our kids are failing everything for three years and then being promoted to high school.” This teaches them that grades don’t matter, and since there is no detention and barely any suspension policies, the newest generation enters a world with no repercussions.

It’s an unfair cycle that the kids, teachers, and administrators are caught in. With no willing teachers, they’re forced to find day-to-day substitutes, who can be a warm body in the classroom, but who, not to their own fault, are sometimes lacking the dedication, skill, and passion of someone who has devoted their life and career to teaching. If there’s a vacancy, meaning no teachers for a certain department, the entire year can be filled with a day-to-day substitute, and it’s unlikely the student will learn as well as they would’ve with a reliable, trained professional. I work in the middle school, and I remember hearing about a student who didn’t have an English teacher for three years.

As O’Leary and I end the interview, another long-time teacher walks into the room. We talk about ghosts, the infamous lightning strike, and how the school was rumored to be built on a mafia burial ground. I think less about the spirits that may or may not haunt the hallway, and more about the ones that exist right now. O’Leary and Threats, pouring their time, energy, and soul into the youth of a troubled America. Laurel Ulrich, in 1976, famously said “well behaved women rarely make history.” Maybe what we need is an attack on the system, a prioritization of trust in teachers, a return to moral standards and values, with consequences to match. Back in Threats’ office, her walkie-talkie fuzzes on with another problem, as kids scream down the hall. She runs, in hot pursuit, and winks at me before rushing out the door, “If I could run this building the way I want to, we’d be alright.”